Palangi Loi

31/03/2006 - 13/04/2006

Production Details

By Sebastian Hurrell

Directed by Simon Ferry

Tongatapu is a defiant island that lies at sea level in the middle of an ocean plagued by hurricanes, tornadoes and floods. Such is the life of Tafi, a half caste Tongan with white skin growing up in Tonga – a paradise of contradiction.

Learn the palangi way and make money and be happy. Speak English, learn maths and drink tea, watch TV and play with fancy toys and be the envy of your friends.

But Tafi doesn’t want to do these things! He wants to climb trees and swim in the deep waves and sing Tongan songs and drink kava and maybe even kiss Luisa.

No one said growing up would be easy.

CAST

Sebastian Hurrell

Erina Daniels

Semu Filipo

Theatre ,

1 hr 45 min, incl. interval

Authentic feel to new Tongan play

Review by John Smythe 09th Apr 2006

When it comes to making plays, some cultures enjoy the great advantage of having an entrenched central conflict that provides a natural source of dramatic energy. The British, for example, have the class system. Where would its vast theatrical heritage be without it?

Māori theatre naturally draws on tradition v modern ways, country v city, a long history of inter-tribal conflict and an uneasy treaty between Māori and the Pakeha descendants of colonial settlers. There is also a strong mythological heritage and kapa haka ritual, inherently theatrical and non-naturalistic, that allows different levels of reality to play out between temporal and spiritual planes.

Similarly Pacific Island theatre, as made in New Zealand, is underpinned by strong mythologies and dynamic forms of cultural expression, and draws its dramatic conflict from a natural wellspring of old ways v new ways, the old home in the Islands v the new home in Niu Sila, PI values v Palagi (or, as the Tongans spell it, Palangi) values.

What makes it different from Māori theatre is that Pacific Islanders in New Zealand have not been colonised in their own land, or not in quite the same way, anyway. They have chosen to move here, or a parent or husband/father has chosen on behalf of the family. To generalise, Niu Sila is approached as the land of opportunity and simply being here is to live in cultural conflict, experiencing identity crisis as a way of life, at personal, family and community levels.

In many ways, PI-in-NZ theatre has lots in common with homegrown theatre generated from other immigrant cultures, like – to take just two of many examples – Jacob Rajan’s Krishnan’s Dairy (1997) and, most recently, Katlyn Wong’s Mui, both of which blend romantic mythology with contemporary reality in the process of articulating the present way of being, at the collision point of past experience and future expectations.

And so to Sebastian Hurrell’s Palangi Loi / Tongan White Boy, which adds to the PI and immigrant culture genres while distinguishing itself by being set in Tonga. Rather than place his conflict in the ‘promised land’, Hurrell traces pre-pubescent Tafi’s final year in Tongatapu before he and his Tongan father and Palangi mother (nearly 20 years in the Islands) make the big move to join Tafi’s much older siblings in Niu Sila.

Two years in development, with director Simon Ferry, it exudes authenticity by sharing the subjective experience of Tafi, a bright, inquisitive boy who resists puberty, the move to New Zealand and the privileges Tongans want to bestow on him because of his relative whiteness. Perhaps too often in the play, he insists he is Tongan when they call him Palangi.

In one of the school scenes – which cleverly slip in facts and figures about Tonga while keeping the story going – Tafi and his best mate Va’inga get into trouble for talking. But when Va’inga gets the whack with the big ruler then the teacher goes to use the small one on Tafi, he insists on getting the big one too.

Likewise it is important to Tafi to make it as a rugby player, despite his small size and having to learn the unofficial and ruthless Tongan rules from his old Papa (grandfather). He comes through a winner on that score, too. Which doesn’t mean it is not a profound shock, and something of a coming-of-age experience, for Tafi to confront the domestic violence Va’inga is subjected to, especially when he may have contributed to the tragic outcome.

Highlights on the comedy side include a boy-boy scene built around growing sexual curiosity, and the boy-mother scene that follows, where Tafi is told more than he wants to know. The God-fearing Aunty Mele’s machete-wielding fury at discovering her man has another woman is also a comic gem, finally poignant.

Woven through the ‘real life’ stories are the Tongan creation myths that simultaneously delineate the culture’s distinctive qualities while showing up what it has in common with others, not least its caste-based, monarchy-ruled class system. While more could be made of this, it’s worth confirming that political points do get made simply be telling it like it is.

Hurrell himself plays Tafi, swinging between boyhood and manhood, with great physical dexterity – his solo evocation of the rugby match is a show-stopper – and a compelling blend of intelligence, toughness and vulnerability.

Erina Daniels triples splendidly as Tafi’s still unassimilated Mum, his slow-going Papa and the wacky school teacher. Some script attention could be paid, I feel, to the credibility of her cultural awkwardness after nearly two decades, although I’m sure its based on a valid premise. What does ring true is he fear of feeling like an outside when she returns ‘home’.

Semu Filipo also triples wonderfully, as "don’t call me dummy!" Va’inga, Tafi’s hard-working father and Aunty Mele, the disciplinarian with a heart of gold. Despite the substantial frame he inevitably brings to all roles, the changes at his core of being produce three fully credible people.

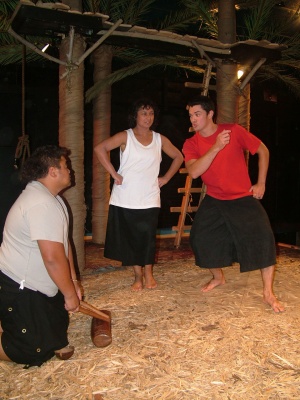

All three actors contribute to the mythology sequences, and the easy transitions between fact and fable, the different characters, and the various settings are down to director Simon Ferry, who also designed the stylised earth-mound set, well lit by Laurie Dean.

The rousing Kailao finale (often described as the Tongan haka), with its spinning, candy-striped, show-biz spears, marks the end of the school year and a means by which Tafi claims his cultural identity. It ensures a feel-good ending to a play that leaves us with plenty to think about, if we so choose.

Palangi Loi could – and should – tour throughout New Zealand, not to mention Tonga and other Pacific Islands, to cultural festivals, perhaps. I have no doubt that as well as attracting adult audiences (it was an almost full house last Saturday night), it would be ideal for school groups from Intermediate upwards.

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Comments