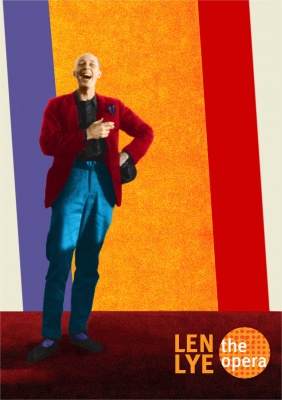

LEN LYE the opera

05/09/2012 - 08/09/2012

Production Details

The colourful life of Len Lye, the one-of-a-kind artist and filmmaker, is now the subject of a unique 21st-century opera.

World Premiere: 5-8 September 2012 at the Maidment Theatre, Auckland

LEN LYE the opera is based on the dramatic life of one of our most original artists. As an opera in the contemporary sense, it is a unique mix of music, poetry, theatre, dance, costumes, set design and film, with a cast of top national and international singers, musicians and performing artists. Eve de Castro-Robinson’s lively music incorporates jazz, dance music and other elements that reflect Lye’s art and personality.

The opera tells the story of one of the most colourful and important artists to have emerged from New Zealand. Born in 1901, Len Lye grew up in this country, moving to London in 1926 to embrace the excitement of modernism and the Jazz Age. In 1944 he moved to New York and lived for the rest of his life in its bohemian art world. He gained a worldwide reputation for his films and sculptures.

Along with his artistic triumphs, Lye experienced two contrasting marriages and ongoing battles with the art establishment. Despite these battles, Lye never abandoned hope or energy – he continued to struggle, to dream, to re-invent art – and to shock the orthodox with his views about art, clothing, politics and marriage.

When he died in 1980, Lye left his art to the people of New Zealand. His animated films and kinetic sculptures continue to excite imaginations young and old, here and around the globe.

LEN LYE the opera

5-8 September 2012 at 8pm

Maidment Theatre

8 Alfred St, Auckland

Tickets on sale at www.maidment.auckland.ac.nz or phone: 09 308 2382

For more information visit www.lenlyeopera.auckland.ac.nz

2hrs 10mins, incl. interval

Len me your ears!!

Review by Sharu Delilkan 13th Sep 2012

I’m always a sucker for a live band or in this case orchestra on stage. I realise that it comes with its own set of technical difficulties but being a live music fiend seeing them on stage the minute I entered the theatre made me smile.

And of course it would be remiss of me not to mention the amazing hats that adorned all the members of the orchestra, including the artistic director/conductor Uwe Grodd, which had my seal of approval, being a hat person myself.

You probably know by now that I don’t purport to be an opera expert, although I love the dramatic side of an operatic production. But on this occasion I was privileged to have a very good friend of mine Jennifer Scott, who was visiting from the US, accompany my hubby and I to the much anticipated premiere of Len Lye the opera. Having spent the last four years in the US watching world class opera, I feel compelled to occasionally quote her in this review as an informed source. [More]

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Story, music, visuals and colour merge to inform, entertain and move

Review by Robbie Ellis 06th Sep 2012

New opera is that strange beast that requires years and years of gestation. LEN LYE the opera began as early as 2001 when composer Eve de Castro-Robinson read Roger Horrocks’ biography of the New Zealand artist. When I was a student of Eve’s and she was writing some preparatory shorter works in the early 2000s – Len Dances for orchestra and Len Songs – it seemed implausible that they would ever lead to a fully produced and staged opera. After years of dogged persistence for funding and the support of many of her colleagues at the University of Auckland, the work was finally realised in its première performance last night.

The opera is structured as a biopic, tracing the life of Len Lye (1901-1980) from formative childhood experiences to an old age recap: “his life passing in front of his eyes,” as the programme book puts it. Across such a vast time scale, forming a cohesive narrative will always be difficult, but this production succeeds in this regard.

At the back of the stage resides a 13-piece orchestra directed by Uwe Grodd, just behind John Verryt’s set of precariously curved wooden platforms which evoke the flow and sweep of much of Lye’s sculpture. It is on this backdrop that episodes from Lye’s life are grouped into five short acts.

For the first two (‘Cape Campbell 1908’ and ‘Wellington 1921’), the principal character is played by two performers at a time. Baritone James Harrison plays the adult Len, looking back to his past and occasionally interacting with his younger selves: Daniel Sewell as a boy discovering the kinetic properties of objects which would inform his later work while coping with an abusive step-father; and Will Barling as a young, independent-minded artist going against the conservative strictures of his Wellington art school.

Acts three and four (‘London 1928’ and ‘New York 1944’) get into Lye’s professional and personal lives. Set against the vibrant artistic social scenes of these two cities, we see him meeting his first and second wives, his extra-marital dalliances, his artistic output moving from painting to film to kinetic sculpture, and the political and commercial obstacles he encounters.

Roger Horrocks has packed a huge amount of detail into the libretto and fortunately the episodes move fluidly from one to the next, with nary a jagged transition thanks to the sterling efforts of dramaturg and director Murray Edmond. There are points in the libretto which suffer from burdensome, unpoetic literalism and don’t marry well with the music – “pursuit of happiness is our theme / the individual is supreme” sung by a Bob Dylan-style busker is one such clanger – but for most of the piece the text successfully treads the fine line between educating and emoting.

Given the lengthy span of time this opera encompasses and its biopic format, it’s inevitable that some of the material suffers from a once-over-lightly treatment. I’m particularly thinking of the moments Len meets his two wives: on both occasions, no sooner have the most cursory of courtships taken place and relationship platforms been established, than the marriages are on the rocks.

The lead-in to the interval (between London and New York) is a little contrived: there’s an abrupt and perfunctory change of mood into Lye making British propaganda films during wartime, and preaching about a peaceful future full of artistic freedom.

However all is forgiven when we take in the riot of colour, both visual and musical. Len’s early twentieth-century New Zealand childhood is depicted with a palette of greys, browns and drabs and a musical style I can best describe as ‘the modernism of unease’, but even this is offset against the sheer beauty and vividness of a sunny day at the beach, captured on video.

The visuals projected on the back wall, directed by Shirley Horrocks, are surely as integral to this opera as its libretto or music. They incorporate bespoke HD video, Len Lye’s own paintings and films, footage of his kinetic sculptures, date- and time-stamps to indicate change of location, archival stock footage of London and New York, and a wide variety of other imagery and colour.

The adult Len is practically never clad in anything boring – reds, teals, greens, even mustards show a keen sense of individualism. Eve de Castro-Robinson’s music supports this to a tee, which draws on a huge variety of stylistic influences. Aside from the aforementioned Dylanesque busker and the dour introductory genre of New Zealand Historical Opera, de Castro-Robinson evokes piquantly snobbish Victoriana in a Wellington art class, and nobody calls up a tinkly cavalcade of wonder quite like Eve for the perfectly paced episode of Len and his second wife Ann gazing at the stars over Martha’s Vineyard.

But it’s jazz that permeates the score and gives it its drive – after all, some call Len Lye “the father of the music video” for how he integrated jazz music and paint on celluloid in his early experimental films. A Charleston rhythm turns up all through Len’s time in London, a motif common to both of de Castro-Robinson’s earlier works, Len Songs and Len Dances.

Roger Manins’ sultry, slinky tenor saxophone totally sells the mutual seduction of Len and his first wife-to-be Jane in a cha-cha-tinged meeting. Moving forward in time, energetic be-bop starts the second half with a bang, announcing the urgency and vibrancy of New York City’s modernist art scene in the 1940s.

We have plenty of opportunity to see Lye’s art, and it’s this body of work which both Eve de Castro-Robinson and Roger Horrocks have advocated so persuasively. Early boyhood sketches lead to paintings inspired by Māori, Polynesian and Australian Aboriginal motifs (with subsequent research, I learnt that Lye spent considerable time in Samoa in the early 20s, although the creators of the opera chose not to address this directly). Early experimental video for the British General Post Office Film Unit led to an obsession with the wild movement of both nature and the human body. The stylised half-dance half-sport gestures of the man with the tennis racquet in Lye’s 1936 film Rainbow Dance are replicated on stage by a backlit Will Barling projected onto a white sheet.

However, it’s kinetic sculpture that really ties the show together. The opening scene sees ‘Len as a boy’ playing with a piece of driftwood, exploring the flow of the line and its movement in the breeze. This sequence connects with Lye’s late-career work of designing pieces which would only be realised posthumously, such as the Wind Wand on New Plymouth’s coastal walkway.

In Act Four, Len clambers over half of Row D to install a smaller wind wand in the stalls. I don’t want to give away the exact surprise, but I too was caught up in the audience’s spontaneous delight and amazement!

In the final act (‘New Zealand 1968’), Len revisits his boyhood home along with his second wife Ann, reconnecting with his childhood inspirations and bringing the story full-circle. We once again see ‘Len as a boy’ playing with that piece of driftwood, as the adult Lye is surrounded by his life’s work, calling back characters from the past and consolidating his artistic legacy.

The ending is genuinely moving: even though the texture is overburdened with voices on top of voices, the apotheosis-like end to a life’s journey in art, culminating in ferociously metallic crackle and graunch evoking one of Lye’s kinetic sculptures, supplied expertly by percussionist John Bell and drum kit player Ron Samsom.

I regret to say that the ending is by no means the only point in the opera where the words cannot be understood. For some bizarre reason, many instruments are miked and amplified through the front-of-house PA, while the voices are not. Appreciating fully that opera performers are expected to sing unamplified, it baffles me why de Castro-Robinson, Horrocks, and sound manager John Coulter let so much of the text be unintelligible even when the audience works hard to discern it.

Artistic Director Uwe Grodd conducts his thirteen-piece orchestra and dictates the pace with consummate professionalism. While having the orchestra visible on stage means it’s hard for them to keep a lid on their own volume relative to the singers, it does mean we can enjoy so much of Eve’s genius orchestration more clearly. The most unusual aspect is an unusually high number of flutes – four players taking on many doublings – and this gives the composer a huge variety of sounds that are seldom heard either in chamber music or the larger texture of a full symphony orchestra.

All of the players in this orchestra are top-notch professionals. Some come from the world of new music, some from the world of jazz, but all are unified in a coherent musical vision. Special mention has to go to Ron Samsom for his incredible sensitivity to the changing role of the drum kit in the texture, and to Andrew Uren for the wondrous variety of tone he can achieve on clarinet and bass clarinet.

The cast of twenty is less even in quality, although the standard among the principals is top-notch. The bulk of the action falls on the shoulders of James Harrison. While he isn’t as frenetic and relentlessly energetic a character as I thought the real Len Lye to be, he brings stage presence, a solid, expressive voice, and a range of characterisations from naivety to gravitas which makes him watchable and compelling across the many ages of the man.

Austrian soprano Ursula Langmayr as Len’s first wife Jane has an immaculate, silvery tone, bringing sensuality in spades. Napier-raised Anna Pierard brings a flexible American-inflected voice and faultless characterisation to Ann, Len’s second wife. Partnership with such a man as Len clearly weighs heavily on her shoulders, but the two of them develop a rapport which is genuinely moving.

Three ‘frustrater’ roles are combined in baritone Te Oti Rakena: a New Zealand art teacher, a London dealer and a New York collector all thwart Lye’s ambitions with haughtiness and high theatricality. Towards the end of the work, tenor Philip Griffin brings a moment of humanly relatable pathos as Lye’s sympathetic but pragmatic New York art dealer, who finally has to take Lye off the books.

There were some scrappy rhythms among the chorus of ten, who appear as Wellington art students, London socialites and New York proto-hipsters, but they rose to acknowledge the gift of having the tastiest tunes in the opera. I imagine the unison issues in this difficult music will sort themselves out over the run.

Overall, I feel that Eve de Castro-Robinson, Roger Horrocks and the rest of the creative team intend LEN LYE the opera to be a major statement of advocacy for the overlooked genius and forward-thinking artistry of Len Lye. Biopics have inherent structural pitfalls, but careful shaping of scenes and the often ingenious merging of story, music, visuals and colour have created something both informative and entertaining, not to mention moving in places.

Setting aside the sound balance issues, this is a landmark multimedia production which deserves to be seen far more widely than just four nights in Auckland. If you can get a ticket, go.

_______________________________

For more production details, click on the title above. Go to Home page to see other Reviews, recent Comments and Forum postings (under Chat Back), and News.

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Comments

Dronevil October 18th, 2012

Hi Robbie,

I'm a member of the sound crew of this opera. I apologize about the sound issue. Just to provide some insight about it here. John Coulter and us insisted that each actor/singer should have an lapel microphone so we can amplify their voices through the PA speakers, especially when there is a loud band behind them. However the administration department kept telling us there is no budget for it so there was nothing we could do.

Sorry again,

Dronevil

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Stimulating work deserves longer life

Review by William Dart 06th Sep 2012

Ten years in the making, with a full house on opening night, Len Lye the Opera was an arresting piece of musical theatre.

A clever libretto by Roger Horrocks pretty much nailed the maverick Kiwi art hero and Eve de Castro-Robinson laced it with stylish, zesty music.

LLTO set off with an onstage band, under the hip baton of Uwe Grodd, moving us from clamour to charleston; then, over shifting harmonies, James Harrison’s Len Lye introduced his life journey. [More]

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Comments

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Comments