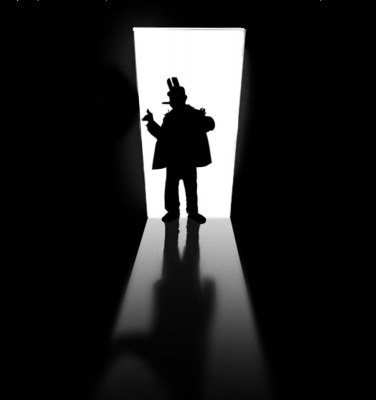

ORDINARY DARKNESS

Hen & Chickens Theatre, Islington, London

14/11/2012 - 01/12/2012

Production Details

“Power is not destroying something. That’s just destroying something.”

Flic, Becca and Max each have their own motives for squatting a mansion in London; Flic wants to defy society’s constraints, Becca goes where the party is and Max… well, he keeps his reasons close to his chest. But the rot has set in and then Max brings home an unwelcome guest; a fat cat city banker who represents all that they despise and all that they want to destroy. And, just maybe, they will.

At Hen and Chickens Theatre, Islington

14 November – 1 December 2012

PREVIEW NIGHT: Wed November 14

BOOK NOW

Tix coll 15mins before

£10.00

Cast:

Jonathan Bidgood – Mr Banbury

Constance Tancredi-Brice – Becca

Lauren Cooney – Flic

Sam Webster – Max

Design:

Kate Lane – Costume/Set

Louie Whitemore – Set/Costume

Nic Holdridge – Lighting

alchemy live art (Martyn Duffy & Mark Trezona) – Sound

Crew:

Sarah Robertson – Writer

Stella Duffy – Director

Olly Hawes – Associate Director

Emma Deakin - Producer

Kylie Vilcins - Production Manager

Freyja Baker - Stage Manager

Kate Hodder - Marketing & Graphic Design

1 hr 10 mins, no interval

Paddling in murky waters

Review by Janina Matthewson 18th Nov 2012

Ordinary Darkness by Sarah Robertson so wants to be about something. In fact, it wants to be about two things: economic theory, and human manipulation.

It is the story of two wilfully naïve young girls being unwittingly coerced into becoming the only employees of a makeshift brothel. It’s about young people fighting unthinkingly against some evil they’ve not really defined but that they’re sure exists within the corporate model and, by extension, the corporate man.

The story centres around Flic (Lauren Cooney), a passionate and idealistic youngster who’s shacked up with her best friend Becca (Constance Trancredi-Brice) and Becca’s boyfriend Max (Sam Webster). The requisite triangular sexual tension is in full force and made all the more complicated by the ‘suit’ Max has dragged into their squat in the form of Mr Banbury (Jonathan Bidgood).

Accused by the others of playing the innocent while she’s truly a Lady Macbeth, Flic is insistent that she’s an honourable warrior for a cause we never truly learn. We never learn it, because she herself doesn’t know what it is. Which is fine, except that she seems so sure. Sure of what? Simply that the proverbial ‘man’ needs to be taken down a peg or two?

As things play out, Flic is less the Scotsman’s lady than her supposed friends insist. Rather she is Macbeth herself: coldly manipulated into acts of evil no one has thought through. But as with Macbeth, she is driven by external forces to do something a part of her wanted to do anyway.

To keep up the Shakespearean comparisons, Becca is surely the group’s Ophelia. Singing nursery rhymes, speaking like a child, and cavorting in animalistic play acting, she is indulged by Max and Flic, who mock her behind her back while stirring the cauldron of their own illicit affair. She is adept at remaining blind to the betrayal she is suffering, or at least at convincing the others of her blindness.

Thrown into the mix, Mr Banbury is the archetypal corporate hack who just might have redeeming features. He waltzes is, misogyny flag ablaze, taking a while to realise that he’s not been brought here to party. Once he’s been a little tortured, however, he’s revealed to be the normal person most of us are.

There is a lot of energy behind this production. The four actors have a sense of enjoyment about them that is quite captivating to watch. They clearly care about what they’re doing and have worked hard on it. Unfortunately their enthusiasm can’t quite cover the muddiness of the interpretation.

Ultimately Ordinary Darkness just doesn’t quite get there. It gives itself the opportunity to look at the arguments surrounding the current economic tensions but squanders it by having characters who don’t really understand their own points of view. It sets up a pressure cooker of twisted, scared, and devilish characters, but never really explores what they’re going through and what they could be capable of.

Lauren Cooney gives a strong performance as Flic, playing her as a convicted crusader and managing to avoid any hint of self-righteousness. However something about this jars with the character as she is written. Because Flic doesn’t know what she’s crusading for; she’s really a lost and confused girl following the first person who’s managed to convince her he is interested in what she has to say. There is so much to explore here that is sadly left alone.

Similarly, there are more questions to be answered with the other characters. Is Becca really that deliberately simple or is she actually high all the time? Constance Trancredi-Brice seems to rely a little too much on the childishness of the character without letting us see the real reasons for it.

Mr Banbury’s transition from creepy, sex-obsessed banker to someone who might actually do reasonable things with the money he earns is not unexpected, but is brushed over enough that it is not quite convincing. I really want to know what he thinks about the economic divide and how that affects him, and he so nearly tells us.

Of everyone, Sam Webster as Max is in the clearest and strongest position as someone who, yes, is after money, but really just has a thing for controlling those around him. His skill at convincing people of contradictory beliefs is matched only by his evident enjoyment at doing so.

Added to the murky character interpretation are some somewhat confusing staging elements. Portraying brutal violence in an intimate theatre is a challenging task, but done effectively can be quite magical. Director Stella Duffy avoids the issue completely, choosing instead to have the actors speak out the actions they’re performing, while their victim reacts. While there is a chilling aspect to this, as we see more clearly the relish the attackers take in their work, it doesn’t have the impact it could have.

It doesn’t help that it’s not always clear whether what their saying is always what their actually doing. It seems that sometimes they’re saying what they want to do, while doing the opposite, and at other times it’s literal.

There is a lot of potential in Sarah Robertson’s script, but it could have gone so much further. It tiptoes into political waters where it should wade, and it shows us characters who are broken without truly exploring how or why.

If a play is what it leaves you with, Ordinary Darkness is a play about a grim situation, and I feel the effects of that long after seeing it.

It plays at the Hen & Chickens Theatre until the 1st of December, with performances at 7pm Tuesday to Saturday, and Saturday at 3pm.

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Comments