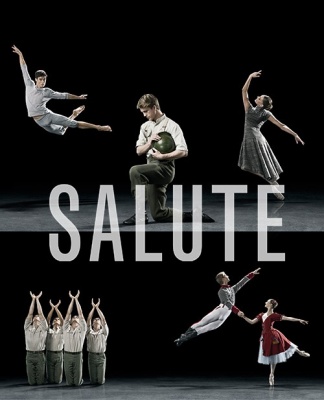

SALUTE - Remembering World War

ASB Theatre, Aotea Centre, Auckland

17/06/2015 - 21/06/2015

10/06/2015 - 10/06/2015

Regent Theatre, The Octagon, Dunedin

03/06/2015 - 03/06/2015

Isaac Theatre Royal, Christchurch

28/05/2015 - 30/05/2015

St James Theatre 2, Wellington

22/05/2015 - 24/05/2015

24/06/2015 - 25/06/2015

Production Details

They went with songs to the battle, they were young.

Straight of limb, true of eye, steady and aglow.

They were staunch to the end against odds uncounted,

They fell with their faces to the foe.

They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old:

Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn.

At the going down of the sun and in the morning,

We will remember them.*

The Royal New Zealand Ballet is honoured to collaborate with the New Zealand Army Band and distinguished New Zealand composers and choreographers Dwayne Bloomfield, Gareth Farr, Neil Ieremia and Andrew Simmons, in this special programme of works to mark the centenary of World War One.

Alongside classic pieces by Johan Kobborg (Salute, New Zealand premiere) and Jiří Kylián (Soldiers’ Mass, last memorably performed by the RNZB in 1999), Neil Ieremia and Andrew Simmons will create two world premieres.

Dear Horizon / 22 minutes

Choreography: Andrew Simmons

Dancers: Abigail Boyle, Clytie Campbell, Kirby Selchow, Tonia Looker, Mayu Tanigaito, Hayley Donnison Paul Mathews, Loughlan Prior, Shane Urton, Shaun Kelly, Kohei Iwamoto, MacLean Hopper

Soldier’s Mass / 30 minutes

Choreography: Jiří Kylián

Dancers: Shaun Kelly, Paul Mathews, Kohei Iwamoto, Shane Urton, Loughlan Prior, Joseph Skelton Jiang Peng Fei, William Fitzgerald, MacLean Hopper, Damir Emric, John Hull, Harry Skinner

Salute / 23 minutes

Choreography: Johan Kobborg

Dancers: Lucy Green, Bronte Kelly, Katherine Grange, Alayna Ng, Yang Liu, Lori Gilchrist Damir Emric, Tynan Wood, Joseph Skelton, John Hull, Fabio Lo Giudice, Jiang Peng Fei General: Jacob Chown

Passchendaele / 12 minutes Choreography: Neil Ieremia

Images used are by Visual Artist, Geoff Tune. From his Red Earth series.

Dancers: Abigail Boyle, Alayna Ng, Adriana Harper, Kirby Selchow, Hayley Donnison, Lucy Green, Clytie Campbell, Elisabeth Zorino, Mayu Tanigaito, Madeleine Graham Paul Mathews, Damir Emric, William Fitzgerald, Joseph Skelton, Tynan Wood, Jacob Chown, Kohei Iwamoto, Shane Urton, Shaun Kelly

There will be one interval of 20 minutes and two 5 minute pauses. Please be seated by 7.30pm as latecomers will not be admitted until a suitable break in the performance. Finish approx 9.30pm.

Andrew Simmons and Gareth Farr would like to dedicate the world premiere of Dear Horizon to the memory of Jack Body (1944 – 2015).

Dance , ,

2 hours

Movement knows no bounds

Review by Kim Buckley 25th Jun 2015

The irony of sitting comfortably and safely with my seven year old son in an iconic theatre watching artistic interpretations of the meaning, memory and sacrifice of war did not escape me. I am a pacifist at heart. I do not do well in conflict. But I know that if my son’s life were at risk, I would do everything in my power to save him. Even go to war.

The mixed bill that the Royal New Zealand Ballet presents us with commemorates WW1. Four works by four very different choreographers from different eras, nationalities and ethnicities all relay similar ideas. Because no matter where we come from, war’s harshness and brutality all report loss, courage, sacrifice, fear, hopelessness, bravery, horror, catastrophe, inhumanity, cameraderie… and more. Representations of all of these are on stage before my eyes.

The New Zealand Army Band performs live and magnificently supports the dancers with commissioned and existing pieces conducted by Captain Graham Hickman.

Andrew Simmons’ Dear Horizons opens our show. What I see looms out of the darkness, bodies strewn as one soldier walks amongst them hand over heart. Above him is an ominous sculpture of netting, fabric crosses and long poppies, designed by Tracy Grant Lord. It does indeed manifest represented media images of war. Lamenting movement is encased by the sounds of violins and cellos, followed by striking and percussive drum and brass by composer Gareth Farr. There are six men, six women, six couples. The men support the men, the men support the women, and the women support the men. But there are no women supporting women. Why I wonder? The dancers’ movement and gestures elegantly and gracefully canon through various ideas, including those of joy, loss, leaving and death. I imagine the emotional experience of these represented couples has no boundaries of faith, ethnicity, or age. Simmons cites this piece as not specifically following a narrative, but gives full discovery to the audience, to our own imaginations and interpretations. That is, war creates rituals of loss, at once unique and similar.

Jiri Kylian created Soldier’s Mass in 1980 for the Nederland Dans Theater 1. At the time, it was hailed as an extraordinary choreography, for no doubt its political substance as well as its structure. It still is. So good, I was unable to ‘enjoy’ it. I felt hammered by the relentless drudgery of the energy, and the constant drone of the score by Bohuslav Martinu (1939). For like war, this piece just goes on and on and on… I kept waiting for it to be over. This must have been what it was like for the soldiers in the trenches, feet wet for months, mental and emotional exertion of constant artillery, and watching their mates die. The opening image of soldiers moving like poppies in a windy field on a red arched horizon is burnt in my mind. Waves of soldiers, one by one falling all over the place, comrades under arms, grave and sober images of pushing through, fighting on their knees if they have to. ‘All for one and one for all’. The dancers bend their bodies in half and in three lines of four, they look like unmarked headstones. Suddenly they are pulling each other through in trios, they are so deathly tired. I applaud the energy of the dancers because this piece is so heavy. Suddenly, it is over. The shirts come off, naked torsos are revealed, the soldiers are vulnerable in their mortality. My only objection to this piece, comes from its contemporary finish. The only female (among a piece for 12 male dancers) put her shirt on for the bow. Surely, in 2015, New Zealand is ok with the female breast for art’s sake?

A light-hearted and fluffy choreography from Johan Kobborg, Salute was originally choreographed for student dancers of the University of North Carolina School of the Arts in 2010. The portrayed universality of youthful and unabashed soldiers and pretty besotted girls is saccharine. ‘Girls love a man in uniform’ seems to be the fine line here. But underneath all this, is the uncertainty of war. Strong muscular boys in uniform may be strutting their stuff like peacocks, and bravely asking a girl for a dance, but this might be the last time they kiss a girl. This might be the last time they dance. They just might be on the way to their own very real acknowledgement of impending death. Kobberg’s choreographed frivolity has an underlying sadness tenderly attached.

As the curtain goes up on the last piece for the evening, I find myself watching a rectangle that is Geoff Tune’s projection of bloodied skulls in the muddied earth, middle ground, ruined and broken cities. Suddenly Dwayne Bloomfield’s magnificent composition comes pounding out of the orchestra pit at the same time as the signature movement style of choreographer Neil Ieremia comes hurtling across the stage. WOW!! is my first response to Neil Ieremia’s Passchendaele as tingles break out over my body and shivers covere my skin. The music is loud, fast and bold. The movement is relentless, masculine, and devastating. Women support women (finally on this evening of war imagery) and men carry men, lift, support, tumble, and place. They seek solace in the arms of a loved one, they watch their loved ones die, and they let go. This piece is extraordinary. But for me, it is too short at only 12 minutes. Having said that, perhaps this wallop! of choreography is exactly as it should be, iven that 845 New Zealanders had their lives taken so quickly and harshly in the First Battle of Passchendaele on that very, very, very long day of 12 October, 1917.

The language of movement knows no bounds. The RNZB Company is currently full of dancers who know their business. Some of these young dancers are no doubt the same age as some of the men and women who fought or currently fight for our freedom. Lest we forget.

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Dancers give everything they have

Review by Raewyn Whyte 18th Jun 2015

The dancers of the Royal New Zealand Ballet give everything they have to their performances of four quite different works comprising the Company’s contribution to our national commemoration of the centenary of the outbreak of World War 1. Ensemble work is exemplary throughout, with some lovely solos and duets sprinkled through proceedings, and there are opportunities to observe new recruits inn action. For three of these works, the dancers are accompanied by the NZ Army Band under musical director Graham Hickman, bringing a rich brassiness to proceedings and demonstrating the extraordinary sophistication of current New Zealand music for brass bands scored by Gareth Farr and Dwayne Bloomfield.

In Dear Horizon (2015), choreographed by Andrew Simmons for 12 dancers, commissioned for this programme, the dancers are ethereal, elegant and enigmatic, quiet and controlled, with extended arms and torsos arcing upwards and backwards, or curving sideways, rising, falling, swirling, constantly moving beneath a huge canopy (designed by Tracy Grant Lord) which is reminiscent of the barrage balloons designed to deter bomber pilots from raining destruction down on the troops and civilians. Red poppies hang down from long stems, like drops of blood, and these combine to suggest a time of war. The works is abstract, without reference to any time or place or particular event, but the somberness and almost greyscale toning suggests a netherworld, a place where living is an edge state and difficult to sustain.

Farr’s music is rhythmically driving, with passages of solo cello (played by Rolf Gjelsten of the NZ String Quartet) interpolated into the brass band score, and at times in conversation with other solo instruments – an oboe, a trumpet – and plenty of percussion interlaced to hint at the battle in the distance.

In Jyri Kylian’s Soldier’s Mass (1980), first presented here by the Company in 1998, there is no doubting the literal reference of soldiery. Eleven men and one woman in white shirts and taupe trousers, with brown leather belts and feet wrapped on khaki woven layers, stand to attention. Their backs are mostly to us as they face the horizon of battle inscribed on the backdrop. They move in disciplined ranks, breaking up into smaller groups, moving in cannon and counterpoint through patterns designed to achieve military objectives. Their pace and commitment slowly escalates throughout the work to reach a state of extremis, ending with death. They dance to the choral work Polni Mse (Field Mass) by the Czech composer Bohslav Martinu, with segments of dance structured to match those of the score.

Johan Kobborg’s Salute (2010), set in 19th century Denmark to energizing dance music of that period by Danish composer Hans Christian Lumbye, seems out of place in this programme. Both men and women are insouciant and flirtatious, naïve, their attention entirely on what is happening in the ballroom, and oblivious of anything beyond. The men are for the moment entirely fearless as they dance at a ball, before their postings are known and the possibility of ultimate sacrifice is upon them.

And finally Neil Ieremia’s intensely dramatic Passchendaele (2015), for 17 dancers, and just 12 minutes long to match the extraordinary score by Dwayne Bloomfield, also commissioned for this programme. The men are staunch, defiant, furious, deeply committed, following their orders despite the realisation that they are unlikely to survive beyond this day. The women, by contrast, are dizzyingly busy, rushing about to get everything done, all flailing arms and flying hair in the early stages, and later quiet, calm, comforting, compassionate, holding and laying out the bodies of their men for the mourners to honour.

There are moments of calm and quiet in the score to counter the sounds of battle, the urgent pace of action. A solo trumpet plays a quiet pastoral song which ends on a jarring series of notes as the barrage of battle returns, relentless shooting close at hand and big guns booming away in the distance, and the rolling thunder that drops over the dancers like a curtain as they go over the top. Behind the action, chilling projections from the Red Earth series by Geoff Tune morph slowly across a large screen as the viewpoint changes from being at eye level with bloodied ground scattered with skulls, to the far horizon, looking across the bloodied battlefield to the silhouetted remnants of trees and villages and a ruined city in the distance.

Audience reactions to the programme overheard post-show revealed a wide range of reactions. Common to all was acknowledgement of the dancing and superb music. Beyond that, I heard passionate discussion about the experiences of family members at Passchendaele and the way Ieremia chose to reference those events; incredulity that the Kobborg work was included here; defense of the Kobborg work; a complaint that the music was too loud; another that there was too little about these works indicating New Zealand-ness, and a critique that ballet’s refinement and abstraction of form mean it can never deeply engage the audience in issues such as those touched on in these works.

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Comments

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Joining NZ's WW1 commemorations

Review by Dr Karen Barbour 12th Jun 2015

As part of a national tour the Royal New Zealand Ballet performed ‘Salute’ in Hamilton last night to an appreciative crowd. Many other reviews of this programme are already accessible and certainly my comments echo those of others. The programme comprises four works by local and international choreographers, and is performed by a full company of dancers and uniquely, with live music from the New Zealand Army Band.

As part of many commemorations of New Zealand’s involvement in the First World War, the ballet company directors state that they aim to place our stories, memories and heritage at the heart of this programme. For this reason, the world premieres of works by our own choreographers Andrew Simmons and Neil Ieremia should be acknowledged as relevant and worthy contributions to this aim.

Simmons’ Dear Horizon is haunting and evocative, interpreting Gareth Farr’s composition played by the Army Band and guest cellist Rolf Gjelsten, and situated within the dominating, if somewhat perplexing, set by Tracy Grant Lord. Choreographically simple, motifs are layered through ensemble, pas de deux, trio and solos with seamless transitions. The costuming is complimentary to the theme and era, and overall the piece is accessible, providing opportunities to reflect on and recognise how we each cope with conflict and loss, not only as a result of war, but in our lives in general.

The programme continues with Soldier’s Mass choreographed by the internationally recognised Czech dancer Jiri Kylian in 1980. The sophistication of this work is evident in the expanded movement vocabulary, the complex patterning, lengthy canons and use of accumulation and de-accumulation. Although 35 years old, the choreography does not appear particularly dated, and it is apparent that this work has had a defining impact on danced representations of war (not least of all on Simmons’ I suggest, in that some motifs directly references Kylian’s earlier work). A work for twelve men, ‘Soldier’s Mass’ includes Laura Jones dancing superbly, but evidently without any deliberate intention to make a specific point about masculinity or the culture of the armed forces. So it is unclear why one of the 12 dancers is female when the work does seem to be created about and for men, but it certainly added interest for me. The male soloists were variable in this performance, the first seemed to be simply going through the motions, the next personally invested and emotionally expressive. While ‘Soldiers Mass’ represents events in Europe leading into the Second World War, rather than our New Zealand stories, the work is a complementary and valuable inclusion in this commemorative programme.

However, the inclusion of the 23 minute classical work Salute by Johan Kobborg, while danced by the company with simpering commitment and seemingly enjoyed by at least some of the audience, is inappropriate and frankly reduces the overall integrity of the programme. I’d rather not have seen this work at all. The New Zealand Army Band were definitely the outstanding stars of this work!

I looked forward to Neil Ieremia’s Passchendaele, the concluding work in the programme. It is a relief to see the dancers move more freely in bare feet and without bows or boxes. The women shine alongside the men, all plunging into Ieremia’s choreography with enthusiasm from the beginning. The red and black projected images by Geoff Tune of bloodied landscapes along with the red side lighting on the dancers’ skins and (yet more) grey costumes, are a striking and unnerving contrast and the emotional pitch of this work is appropriate for the finale of the programme.

It is disappointing that the work is only a bare 12 minutes. However, the dancers look as though the physical demands of Ieremia’s relentless contemporary movement vocabulary may be too much for them to sustain over a longer time. Within this work are recognisable features of Ieremia’s choreographic style and repertoire – overlapping apparently risky lifts within ensemble work executed with confidence born of hours of rehearsal and attention to detail,, fast paced jumps, leaps, falls and rolls maximising momentum, and recognisable human moments in duet that pull at the heart. Unconsciously foregrounding heterosexual relationships, (as the other choreographers had also done), the men were much more believable as generic soldiers and the women more genuine in their representations of loss. Ending with knocks on the Founder’s Theatre doors recalling the knocks of army personnel bringing bad news from the front, Ieremia’s choreography brought New Zealand history home to us all.

In summary then, two premieres of New Zealand works by the RNZB, both worthy of development and international touring, and a sophisticated historic work that rightfully retains a place in international programmes like this.

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Comments

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Ballets evoking weighty issues

Review by Jonathan W. Marshall 06th Jun 2015

The Royal New Zealand Ballet’s latest mixed bill program, Salute, is another of the international series of events staged to memorialise upon the First World War. Traditionally, ballet has tended to leave WWI to modern dance, in large part because the topic all but defined the newer dance forms as they emerged in the interwar years. It is therefore impossible to watch Salute without reflecting not only upon WWI, but also the history of dance and expressionism as well.

The program is indeed wonderful, in no small part because of the impressive scale—up to 18 dancers on stage—as well as the presence of live musicians in the form of the New Zealand Army Band.

It is however hard not to come away feeling that the otherwise great premieres of the evening—choreographer Andrew Simmons’ Dear Horizon and Neil Ieremia’s Passchendaele—have a beautiful but very old world ambience, not only evoking a historical topic, but also historic approaches to this topic. It is therefore Jiří Kylián’s superb Soldier’s Mass, itself nearly 35 years old now, which is the most successful and critically open-ended of the works included.

The Interwar Dance Scene

It was principally the interwar years in Europe, and especially throughout the German speaking nations, that modern dance as we know it arose, as part of what was then typically called simply “dance theatre” or expressionism. Most of these historic works therefore addressed in some way or another the depleted, wounded and/or defeated character of the German body (as it was then understood), and most constituted an analysis of and call for community. Consequently “choric dancing,” or massed groupings of dancers moving in unison or canon made up a significant part of much of this work.

Choreographers dramatized the relationship of a principal dancer or dancers with this group, the latter representing society as a whole. Mary Wigman especially shone in these roles, and her massive, bleak requiem for the German war dead Totenmal (1929) remains one of the great works of the twentieth century.

The expressionists tended to see their work in opposition to the stringent limits on movement which ballet typically imposes—although most of the key choreographers worked with major ballet companies in the late 1930s, 1940s or post war years. Indeed, one of the best known of these anti-war pieces, The Green Table (1932), was produced by Kurt Jooss, a choreographer best known for successfully blending the new styles with balletic formalism.

Dear Horizon

Simmons’ Dear Horizon is the most overtly historicist of the pieces. The dance is performed beneath a wonderful hanging structure designed by Tracy Lord Grant, and which features an irregular scattering of memorialising crosses leading to a pile of tank traps. The design closely echoes Stanley Spencer’s 1932 murals for the Sandham Memorial Chapel (https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/sandham-memorial-chapel/), and I suspect was directly inspired by this famous work, though the program does not confirm this.

Whatever the case, the allusion is apt as the chapel depicts the melancholy resurrection of the fallen who stand one by one above their comrades, before engaging in a last, lingering dance with their female lovers. The piece is spare, simple, and composer Gareth Farr’s new score is truly wonderful, using nearly ever ounce of musical colour which one can coax out of a musical ensemble made up principally of brass instruments and percussion. When the fury of loss arises, the thunderous, tonally jagged rhythms smash the stage with some force.

Lingering farewells make up a significant portion of the work, and the social effects of war are dramatized through a rather derivative model of male-soldier-linked-to-society-via-female-lover. It’s all very heterosexual, and although the men are elegant and restrained, the mood is—very much like the 1920s and 1930s works it so closely recalls—to reclaim and revalorise masculinity by healing it, and showing these men as active sexual or loving beings.

Politically then, it does seem a bit unreformed. No hard questions about who went to war, why, and so on, are given much of a look in. It’s a straight forward, Romanticist requiem. This should however in no way diminish its appeal. I’ve read a great deal about these long lost works, but to see a new piece all but resurrect their mood is a rare pleasure.

Salute

The third piece in the program is Johan Kobborg’s Salute. Kobborg is renowned for his revival of works by one of the founders of 19th century ballet, Bournoville, and the music here is by Hans Christian Lumbye, who composed for Bournoville and others. This rather metronymic, highly balanced, call-and-response style of music is thus echoed in the equally dated choreography, which basically does the same thing in movement. A hand is offered on one side, then on the other, a single step is taken, and so on. It has the feel of watching an old book of possible choreographic patterns come to life, which is of course what it is.

As a piece of light formalism, the piece is good enough, and it does give an excellent opportunity for each of the rather different male dancers in the work to each perform in turn as the lead within each one of the short segments presented here.

The content however reduces us to the level of frippery, to say the least. It is unashamedly about “dashing soldiers” of the 19th century aristocratic officer-class in uniforms wooing simple maidens. If the gender politics of Simmons seemed somewhat unreflective, that of Kobborg is positively dinosaurian. At least there is one female officer, but rather than exploring the possibility for queering the performance, she too ends up being the second to a male partner.

In most other circumstances I’d be more than happy to go with the flow and enjoy the unreconstructed silliness of the piece, which is surely how it is designed to be taken. Sadly though when you put a work like this into a program largely about honouring war dead and reminding us of the ghastly casualties of modern warfare, a piece which makes joining the military look like a bit of a lark involving fancy uniforms and upper-class dancing with girlies is, I’m sorry to say, really pretty close to being offensive. Something of a poor choice for this program, despite its strengths as a nice enough piece of formalism.

Passchendaele

The program ends with Ieremia’s bleak epic. If Farr’s music has something of a roaring neo-Romantic feeling, the crashing tones and freer, more tonally extreme material used by composer Dwayne Bloomfield here is positively atonal or serialist. Bloomfield even has a few minor moments with people whistling or knocking on doors whilst they are scattered about the auditorium amongst the spectators, thus causing the sound world to really come out and surround us as we listen.

While Grant’s design is muted in tone and colour, Ieremia’s seems comparatively garish and fervid. Like the music, it has more punch and contrast. A black, white and red projection by Geoff Tune of silhouetted, artillery-smashed trees, splashed with blood, rests behind a cast in uniform grey. It’s not at the level of Jacques Tardi’s War Whore [Putain de Guerre] (http://h-france.net/fffh/the-buzz/putain-de-guerre-teaching-jacques-tardis-wwi-graphic-novels/), but slight variations in Tune’s imagery help get the sense of overwhelming force to develop.

Ieremia’s choreography again (like Simmons’) alternates a massed male chorus with smaller groupings of men, or the action of the women. The movement palette is, as one would expect of the sometime director of Black Grace, less architectural than Simmons’ and more curved or expressing more acute angles. The groups seem to scatter and whorl rather than process and twirl. There is even a moment where the movement evokes indigenous warrior actions, as the men partially crouch down on one knee while the opposite arm comes up as if to hold a spear or mere.

Ieremia’s work has a kind of parallelism to it. Whilst Simmons’ dancers occasionally move into the deep shadows at the back of the stage, Ieremia’s dancers often seem locked into tracks running stage left to right, and parallel to the backdrop. Together with the music, this helps give the piece a certain urgency which Simmons’ largely eschews for meditation.

Whilst Ieremia’s work doesn’t quite have the graceful nostalgia of Simmons, it still reflects a kind of yearning for resurrection. And again, compared to works by Jooss, Wigman and Rudolf Laban, I’m not sure what new insight is offered into war or how to express it.

Also like Simmons, the rather abstract space within which the dancers perform is ruptured by a return to heterosexual pairings. After musing on the dance as a more indirect and hence perhaps politically ambiguous response to war, it is rather disappointing to have us yet again witnessing a group of women mourning their male dead.

Passchendaele certainly makes for a high octane conclusion to the program, though here, as with Simmons, the piece seems to sit slightly awkwardly between true abstraction and true dance theatre. In both, dancers sometimes play characters—the deceased male soldier and his home-front love—but at other times do not, and at least for me, it is something of a disappointment when more interesting readings are cut off in both works by a return to the same old story of love lost—surely not the most important one to tell about the global experience of modern war?

Soldier’s Mass

Perhaps the revelation of this program is that by setting Kylián’s work against these precedents, one comes to better appreciate the magisterial qualities of his own highly precise, sculptural work.

Again, we have a choral mass of male dancers performing against a truly sublime pre-recorded score by Czech composer Bohuslav Martinu, which itself features massed male voices in the style of a semi-Byzantine choir. The sepulchral awe and power of the music sweeps through the dancers, who form lines and small groupings before breaking off in canons.

A recurrent motif is the lone male dancer, standing against or apart from his fellows, before falling backwards into their waiting arms and being hoisted up, or other similar dramatic contrasts between mass and individual. Related patterns show small groups of dancers struggling to navigate through ranks of their brethren.

The repetition of these structures, and the manner in which the dominant group typically returns to reclaim, or to box in, such wayward figures, suggests a drama of dissent against participation in the socially condoned madness of war which none of the other works in this program manage to evoke.

Here at last one has a dance drama which could perhaps be read as honouring not just the soldiers but the conscientious objectors, not just the Czech bishops who urged their compatriots to join a supposedly just battle against a murderous foe, but also those Quakers, pacifists and deserting soldiers who stood their ground and said no. In short, this dance—uniquely within this program—is sufficiently open to permit it to embrace multiple dissenting histories.

The performance is also wonderfully queered through the addition of Laura Jones. Kylián is known for his tendency to lay out his bodies as living sculptures, often topless, so that the cleft between shoulder blades and coils of muscle are caught in the sidelight (also designed by Kylián). Famously this proved somewhat controversial when imposed on female members of the Australian Ballet as part of their wonderful staging of Bella Figura in 2002.

Soldier’s Mass overall functions as a kind of unveiling, the staggered bodies taking on the sense of being suspended, lifted upright as if on a breath of wind and hence ready to collapse at any moment. As part of this reduction of the body to its final statuesque beauty, the dancers perform the final section topless, thereby making Jones’ sex unambiguous.

Because in this work none of the dancers takes on an actual character or specific role, this actually works perfectly within Soldier’s Mass. One could read Jones as standing in for one of the many women who fought in the Great War—and there were many more than is usually admitted, particularly throughout the Balkan and eastern fronts, where irregular units as well as Russia’s famous all female battalions were common.

It is probably more appropriate though to read Jones’ presence as a reminder of the diversity of the war experience, which included men and women, heterosexual and homosexual (again, there was a lot more same-sex activity on the battlefront than is typically admitted; do not forget that Britain’s great warrior poets Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen were gay), soldier and pacifist.

There are many other attractions to Kylián’s offering. The wonderful set for example consists of a simple black backdrop slashed along the horizontal by three gently curving, coloured lines which evoke the great flatlands that stretch across the northern regions of the Austro-Hungarian Empire of which the Czech region was a part, the steppe lands that join Germany to the east and Russia. It is worth remembering that the casualties along these eastern lines in the two wars were astronomically large even in comparison to the western fronts. These evocations within the set, in combination with the funereal music, gives the piece an added poignancy.

Perhaps more importantly, the way the set suggests a wide, flat expanse across which the sun bows, helps move the aesthetic away from the somewhat Sassoon / Owen ambience encouraged by the 1920s English-style set of Grant and Tune, and place Soldier’s Mass at once at a greater critical distance from its subject, as well as within a less specific and more abstracted spatial and temporal realm. It is quite simply more satisfying and reflects an ambience closer to that of today rather than looking back to the styles of the interwar period.

Conclusion & a Salute to the RZNB

None of this is of course to denigrate the program. Rather what is so strong, so appealing, and so challenging about this program is that frankly few evenings at the ballet tend to evoke such weighty issues. How should we memorialise war? How do we address this legacy in art? And how does ballet itself relate to the complex histories of art, memorialisation and politics? For the RNZB to wade courageously into such treacherous waters and to pose such questions to both themselves and to the audience is to be greatly admired. Particularly the willingness of the company to tour with so many dancers as well as a stellar live band is fantastic. I dearly hope that further thought provoking national mixed bills are in the offing.

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Comments

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Diversely commemorative dance works

Review by Hannah Molloy 05th Jun 2015

With torrential rain breaking records outside, the audience still surges in to watch the Royall New Zealand Ballet’s Salute in the warm dry Regent Theatre. There is an atmosphere of camaraderie and many conversations about flood water levels and road conditions around the city.

The addition of a live band to a ballet adds a dimension that always surprises me with its depth – I always think I should have learned to expect it but I still enjoy the sense of getting even more from the experience than usual. The New Zealand Army Band plays the diverse scores beautifully and passionately, and conductor Captain Graham Hickman charms his smaller and more overtly curious audience members hanging over the orchestra pit balustrade to see what is happening below.

Salute is made up of four short works commemorating World War One. The works are diverse, but all play on the range of emotions elicited by discussion of war, grief, anticipation, bravado, relief and even the joyous flirtation that can be experienced by young people in times of uncertainty.

Dear Horizon, choreographed by Andrew Simmons with music composed by Gareth Farr, begins with the haunting fragility of music left drawn out, and spare lighting and movement on the stage, and moves through discordant frenzy back to gentleness, leaving the audience with faceless women supporting their men – seeing no evil,perhaps, or is that more a governmental perspective than a woman’s perspective(?) – and a feeling of having been allowed your own individual interpretation without prejudice.

Soldier’s Mass is a work created for 12 male dancers by choreographer Jiří Kylián with music by Bohuslav Martinu. The inclusion of Laura Jones in this piece offers an opportunity for reflection on the difference between male and female physique and movement, not least at the end when all dancers remove their shirts (though when taking their bows, Jones replaces hers. I wondered simply why it mattered and if one, why not all?) Trivial distraction aside, this is a beautiful and poignant dance, with the dancers falling across the stage with the fluidity of a new deck of cards flung across a smooth tabletop.

Salute, choreographed by Johan Kobborg to music by Hans Christian Lumbye, is a marked contrast to the other three pieces, with its jaunty flirtation between soldiers and frisky women. It is fun and charmingly executed, with lots of chuckles from the audience at the petulance of the girls being ignored. I think sulky ballerinas may be my new favourite.

Passchendale, choreographed by Neil Ieremia with music by Dwayne Bloomfield, was a short, intense and emotional journey for an already keyed up audience, from its raging beginning to its desperately sad end. The simplicity of the grey costumes is a foil for the energy and drama of the movement and the backdrop of images from Geoff Tune’s Red Earth series which adds visually to the tension. This work of the four felt the most wrenching and I have to confess to some tears.

This mixed bill is very much a male dancer-focussed show, perhaps unsurprisingly considering its subject matter but it is very different to watch compared to a ‘usual’ ballet and I liked seeing these incredible men as the heroes of the works in every sense of the word. Kohei Iwamoto’s and Paul Matthews’ performances are especially beautiful.

Salute is altogether a lovely way to spend a very rainy evening and I’m very pleased I braved the streaming streets to see it.

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Comments

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Dance dynamism and physical prowess

Review by Sheree Bright 29th May 2015

Dance transforms the time and space in which it occurs through gesture, line, rhythm, phrasing and kinetic energy. Through this movement we are transported to a world charged by dance dynamism. In the contemporary season of Salute, the Royal New Zealand Ballet (RNZB) demonstrates the physical prowess for which NZ dancers are renowned.

It is always a delight to attend the repaired and beautifully restored Isaac Theatre Royal. The RNZB present the evening’s work in collaboration with the exceptional New Zealand Army Band (NZAB) performing live in three out of the four pieces. Interestingly, while I type my notes, the mini-series Band of Brothers is on television showing a particularly poignant episode where allied troops liberate a concentration camp. Marking the centenary of the First World War, Salute, is a mixed bill of four pieces, exploring the themes of war, loss, courage and hope.

The first piece, Dear Horizon, is a world premiere choreographed by Andrew Simmons. A musical score commissioned by Gareth Farr is performed by the NZAB, cellist Rolf Gjelsten and powerful percussionists.

The scene is set by designer Tracy Grant Lord for Dear Horizon as two smoky beams of light from above shoot diagonally across the stage. Camouflage-like netting hangs from the back of the stage and spreads forward with representations of crosses and upside down hanging poppies. The roll of the timpani drums and long slow notes of the cello, played by Gjelsten, beckon a lone soldier to enter, moving through bodies on the ground. The brass instruments of the NZAB begin to play and the women on the floor are supported into sitting position in a ghost-like waving motion. The men dance in sombre unison, opening across the chest with arms outstretched representing how exposed and vulnerable these men are.

Traditional ballet and contemporary movements blend but seem weighted more towards ballet. I particularly notice Mayu Tanigaito. During a brief solo phrase and indeed throughout the dance, her energy brilliantly extends beyond her fingertips giving a magical impression to her performance. There are many movements performed in canon-like repetition. Couples stand next to each other in stillness facing in opposite directions. I feel chills when the music intensifies with chimes (tubular bells) and the dancers express through their vigorous movements the intense energy in the music.

As the men and women walk in melancholy procession, the women’s faces are veiled, perhaps in mourning. The gesture of the women covering the men’s mouths symbolizes the tragedy that they are now silenced.

Christchurch-born choreographer Andrew Simmons states in the program that the themes of war expressed are “not specific to only one war,” and note that “war has shaped and impacted all our nations and lives, whether first-hand in service or as recipients of the liberty awarded to us by the selflessness of our countrymen and women.”

Soldier’s Mass was originally choreographed by Jiří Kylián in 1980 for the Nederlands DansTheatre, and was performed by a cast of twelve male dancers. Such was the intention of the RNZB; however, during the recent premiere in Wellington, one of the male dancers was injured and replaced by Laura Jones. Audience members at subsequent performances have commented on how well she executes the movement rigours of this piece. Indeed, herChristchurch performance is no exception.

There is a strong, slightly curved red line on the backdrop of the set, perhaps representing the setting sun or the end of days. Standing side to side with their backs to us the dancers sway and develop into unison or canon like movements, some seeming to represent the relentless surges of battle as the snare drum persists.

In physics, an object’s mass determines its gravitational attraction to other bodies. Kylián’s choreography, with its energy and perpetual state of motion, seems to convey an unstoppable pull towards the soldiers’ collective fate.

Despite individual movements and expressions, the soldiers are bound to one another, as if some gravitational pull keeps them together as one unit. When the violent forces of war are applied against the soldiers’ collective mass, they resist, accelerate and ultimately falter. The word mass is derived from the Latin word missa and is representative of the ultimate sacrifice the soldiers make: they are sent forth to their ultimate dismissal.

Soldier’s Mass is set to a score by Bohuslav Martinů for a male choir, brass instruments, percussion and piano and is performed with excellence. Like Mr. Kylián, Martinů is a Czechoslovakian expatriate. The music was composed in 1939 in memory of a battalion of young Czechoslovak soldiers who were killed the day after they went into battle in France in World War I.

Salute, choreographed byJohan Kobborg from Denmark (in 2010) offers an upbeat contrast to the other pieces. The music is a selection from Danish composer Hans Christian Lumbye (1810-74) conducted by NZAB Captain Graham Hickman. With playful characterisations, it is a light-hearted portrayal of a group of dapper young officers as they dance with coy young women. They are warmly naïve and distanced from the cold hard realities of war experienced by their comrades in the trenches. The soldiers in this piece are revelling in their freedom and frivolity and a variety of romantic scenarios ensue. The choreography veers more towards the traditional movement vocabulary of ballet with point work, pirouettes, a romantic adagio duet, finishing poses, and applause between various vignettes. With its comedic relief, the piece elicits from the audience many smiles, chuckles and comments like, ‘Lovely’, especially as one soldier, when deciding between two girls, happily courts them both. Dancer Katherine Grange gives a stand-out performance.

Passionately and stunningly choreographed and performed, Passchendaele is brilliant! Honouring the events On October 12, 1917, when, in a matter of hours, 845 New Zealand men lost their lives and nearly 3,000 were wounded on the battlefields of the Somme and Passchendaele, Ieremia also draws on the enduring thoughts and connection between the soldiers in the trenches and the women left at home. This world premiere, a captivating contemporary piece, demonstrates the blending of choreography by Neil Ieremia, a musical score by Dwayne Bloomfield, and wonderful performances by dancers and musicians.

There is a loud, bold introduction. The musicians manage to simulate the sound of machine gun fire. The backdrop projection is a very stark black and red representation comprising images by visual artist Geoff Tune. Dancers propel each other into the air representing ‘going over the top’ from the trenches. The soldiers had well-placed trust in their comrades, but trust in command was misplaced. A dancer stands on the shoulders of another only to fall back tragically onto those still in the trenches. The creative lifts and the kinetic energy of the dancer’s bodies as they torque through space is electrifying

Following the performance audience members behind me exclaim, “Oh! Wow!” and “That was fantastic!” Passchendaele is such a powerful offering that I (and I’m sure many others) wish it could somehow be extended beyond the 12 minutes allowed by the excellent musical score.

Tonight’s performances creatively add to the tributes and commemorations that seek to honour the sacrifice of those who gave their lives in the hope of a peaceful future. A full evening’s work of just one piece would allow for a deeper connection to the themes of war like courage and sacrifice. However, having four offerings in one evening gives us the benefit of different choreographic perspectives. The evening is appreciated for its superb contributions.

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Comments

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

LET’S REMEMBER, BUT NOT REPEAT

Review by Chris Jannides 25th May 2015

The Royal New Zealand Ballet tackles WW1 with a mixed bill of four works that, in essence, are not that mixed. In particular, there are noticeable choreographic and thematic overlaps between three of the works – Dear Horizon, Soldier’s Mass and Passchendaele. But the theme is war, so how can there not be repeated images of dying, sorrow, loss, departure, fear, consolation, heroism, comradeship, etc., etc.? All romanticised with gracefully expressive bodies that curve or explode in tragic anguish and emotively charged eloquence and lyricism.

In the logic of programming – which, in tonight’s performance amounts to curtain-raiser (Andrew Simmons), homage to the ancestor (Jiri Kylian), light relief (Johan Kobborg) and climax (Neil Ieremia) – Simmons’ piece, Dear Horizon, is rightly at the start. Its balletic style signals the company’s allegiance and home territory. It introduces the theme of the evening in a respectful and moving tone. The choreography and the music, by Gareth Farr, are beautifully aligned. A woman next to me (I love getting feedback from strangers during a performance), remarks that the music makes her want to burst into tears. ‘It is so mournful’, she tells me, ‘there is so little redemption in it’. The only thing that I and my neighbour query is the set by Tracy Grant Lord. A gigantic tornado of stuff upstage centre looks like a deranged Christmas stocking from hell! My neighbour notices that one of the dancers accidentally bumps into it. If nothing else, it is definitely unmistakeable and appropriate in what it represents and depicts of the fearful chaos of the battlefield.

Simmons’ Dear Horizon – (is the title a tribute to Kylian’s work, which follows, with its bright-red, curved horizon line across the back of the stage?) – is principally lyrical, with mournful walking figures, sweeping extended gestures, lots of swirling and lifting of bodies in elegant shapes, fluid expressions of emotion, rising and falling forms. At times it is processional, delicate, military (as are all the works with their literal depictions of saluting, marching, standing at attention, etc.). There is airborne stuff, big jetes, a lifting of speed and energy at the three-quarter mark, the mandatory carrying of the corpse above heads (also seen in the other works), as well as much gazing into the distance, sometimes standing, sometimes kneeling – the men gazing into their dreadful future, the women gazing after the departed men and awaiting their return, or not. In fact, this dance has a lot of choreography. So much so that its structural logic disappears as it unfurls itself along its distance, while never seeming to lose its way, thankfully.

If Simmons is the curtain-raiser, Ieremia’s Passchendaele is the climax. Primary differences between the two are that the dancers have dispensed with their soft ballet shoes and are now barefoot. There are all the same movement motifs, choreographic devices, literal references and emotional themes as in Simmon’s work (so I won’t list them again), but instead of an overwhelming piece of sculpture as a set, there is a projected image of a river of blood that slowly morphs into a landscape of charred trees and white sky. The movement is also more explosive and angular, and there is a lot more lifting of bodies. The choreographic structure is transparent in its episodic development. The inclusion of some kapa haka gestures gives the soldiers a distinctly kiwi identity. Interesting also that the more virile barefoot movement language of Ieremia’s contemporary dance style makes the dancers look more youthful than they appear in some of the other works. This is clear testimony to their versatility.

Passchendaele is also the crowd favourite. The music, by Dwayne Bloomfield, has risen to the choreographic demands Ieremia requires of it. While the bandwidth of the other works hovers within a dynamic range that is expected of all professional dance and good choreography – a range that embraces gentleness and delicacy at one end and athletic prowess and virtuosity at the other, all safely held within the bounds of great technique – Ieremia pushes these extremes so there is more energy, more attack, more contrast, more impact. Blasted in this way, the audience responds with excitement and with batteries newly charged. Ieremia’s status as one of NZ’s more successful choreographers is amply justified by this addition to the ballet company’s repertoire.

The visual impact of dancers dancing in canon (not to be confused with the weapon) is always striking and it is the earliest of these works, Jiri Kylian’s Soldier’s Mass, created in 1980, that might be said to have set the initial benchmark and standard for this technique. Kylian’s skill at being able to fluidly arrange and rearrange group formations of dancers is legendary. He added new chapters to the choreographer’s handbook with his signature movement aesthetic and style, along with his appealing and masterly exploration of geometrically staggered movement sequences and weaving patterns. This work is one of the stand-out and most popular creations in Kylian’s extensive canon.

I cannot add anything new to the tomes of literature that Soldier’s Mass will have already attracted over the years. This is one of the classics of 20th century dance. All that’s left is to comment on its rendition tonight. The dancers performed it extremely well, although I found that the solos were slightly lacklustre. However, there was one strange feature, that of a woman in the cast. The original was choreographed on 12 men. In its many recreations on different companies around the world, is it now common to include female dancers? I did not know this. My initial reaction was, ‘Oh, the ballet company doesn’t have 12 men’. But a look at the programme showed that this isn’t the case.

The intriguing thing for me is that ballet here is one of the bastions of artistic conservatism. For instance, although audiences in Europe have been hardened to nudity in the works of contemporary ballet over the last few decades, that is not the case in NZ (except of course in contemporary dance). So in the climax of Soldier’s Mass where the men dramatically discard their shirts to reveal well-muscled torsos, why was the sole female dancer, who had been prominently placed at the front of the stage through much of the choreography, discreetly removed to one of the back lines at this moment? And then, having been topless for the conclusion of the dance, why was she the only one to put her shirt back on for the curtain call that immediately followed? Perplexing! It seems that a token gesture towards something that might be slightly radical was handled in a way that also made it prudish. She then gets the biggest applause, which would seem to undermine the choreographer’s statement about solidarity among fighting men. Just get all the men to put their shirts back on too for the bows, would be my suggestion!

In the three works mentioned so far, Kylian’s Soldier’s Mass sits between Andrew Simmons’ and Neil Ieremia’s works as a proud ancestor with some new offspring. Differences between the latter, as has already been noted, come not so much from their content and approach, but more from the fact of their respective backgrounds – Simmons in ballet and Iremia in contemporary dance. The fourth contributor to tonight’s programme stands in complete contrast to all the rest for its comical and light-hearted take on the subject.

Salute, by Johan Kobborg, matches smartly attired young military men with coyly amorous young women. Its series of short items offer the company an opportunity to get out of the bleak and distressing world of the battlefield and into the flirtatious territory of the ballroom. There is much showing off of skill and technical finesse, featuring the full gamut of well-known classical ballet steps and vocabulary. On top of this there is plenty of tom-foolery involving jealousies, awkwardness between the sexes, confusion about who should be with who, the bonding of star-crossed lovers, punctuated by the exaggerated antics of a buffoonish sergeant major. All gently situated within the melodic tones, world and rhythm of the waltz. In the spirit of overlap between tonight’s works, I am amused to see that amongst the uniformed cast of costumed ‘soldiers’, one of them is a female – but this time she is thematically integral to the storyline. Kobborg’s happy work is infectious and makes the audience very happy too.

The Royal New Zealand Ballet is currently a strong company of highly accomplished and personable dancers. I at no point witness a feeling of uncertainty or shakiness in performance. Their bodies and techniques appear confident, secure and strong. There is consistency of artistry across the board. It is great that a programme such this allows the art form to set aside its hierarchically driven approach and work more tightly as an ensemble.

The live music component from the New Zealand Army Band is an added bonus to tonight’s proceedings. What a privilege to hear such musicianship and to experience this kind of artistic collaboration between dancers, composers and musical practitioners in our community who might not normally associate in this way. The overall production and design elements are also to be commended for their high standards and expert delivery. The Royal NZ Ballet has high demands expected of it every time it steps out on the stage, tonight’s performance more than fulfilled each and every one of them.

Chatting to my neighbour between items, I realise she has become a kind of armchair expert on ballet audiences. For instance, she tells me that the noise people make in the intervals or gaps is a measure of their reaction to what they’re seeing. If the sound goes up, all is good, if people are quiet ‘there is no energy in the performance’. She happily points out that the volume tonight in the audience chat is high. At the same time, I overhear people behind me talking about the price of cod and their disappointment at having bought some fresh fish recently that didn’t last long when they took it home. I amuse myself by trying to connect this conversation to the question of the hopefully longer-lasting impact of theatrical performance and dance.

This evening’s entertainment at the ballet on the theme of war has made me reflect a little on our lives here in New Zealand and on how such events are so distant, both currently and historically, for us. But are they? And for how long? I think also of those few in our armed forces who have fairly quietly been shipped off to the Middle East to face the reality of what we are here tonight safely enjoying and appreciating as art. History goes in cycles, but is at the same time completely unpredictable. Let’s remember, but hopefully not repeat.

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Comments

Raewyn Whyte May 25th, 2015

NB In 1999, The Royal NZ Ballet female dancer Pieter Symonds was one of the performers comprising the necessary dozen in Kylian's Soldatemnis/Soldiers Mass. With her breasts/chest wrapped in crepe bandage when the shirts came off, and for the curtain calls, her performance was entirely memorable, and she was more than equal to the demands of the role. She went on to join Ballet Rambert in London in 2004 and in 2010 won the UK Critics’ Circle National Dance Award for the Outstanding Performance by a contemporary dancer.

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Reminders of war and death

Review by Jan Bolwell 25th May 2015

In the opening moments of Andrew Simmons and Gareth Farr’s new work Dear Horizons as a solitary male figure walks around and across figures lying on the ground in a crucifix position, reminiscent of the mass graves in those WW1 cemeteries. There is an ominous rumbling sound from the New Zealand Army Band followed by a small piercing note trying to break through as one by one the dancers, male and female, rise from the ground. So begins this powerful new work that takes us on both a lyrical and starkly painful journey of fear and personal loss…

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Comments

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Powerful and moving show

Review by Ann Hunt 24th May 2015

Salute. Remembering World War 1, is a true collaboration between the Royal New Zealand Ballet and the New Zealand Army Band. (The Army Band, which accompanies three of the four choreographies, is stunning and is vigorously conducted by Captain Graham Hickman.

Tracy Grant Lord’s dramatic hanging is the centre-piece for New Zealand choreographer Andrew Simmons’ Dear Horizon – a world premiere. Scraps of letters and diaries to and from soldiers at the front hang from a fall of netting. Some criss-cross over each other, resembling the track marks of battle tanks. Slender poppies hang upside down. The installation resonates with images of soldiers being trampled in the mud of Gallipoli and Passchendaele.

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Comments

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

War and its effects placed centre stage

Review by Deirdre Tarrant 24th May 2015

As the country honours and acknowledges those who fought and those who fell in WW1, the significance and scope of the subject and the immediacy of its relevance makes this programme of four short works unique for our national company and for ballet itself in this country. The season collectively titled Salute has both an historical perspective and a contemporary positioning, and places a subject before us that is centre stage at the moment for the country.

The four works here reflect on and respond to the huge sweep and impact on families and on the change to the world that the Great War made. The title work Salute by Johan Kobborg with the wonderful New Zealand Army band playing a collection of compositions by Hans Christian Lumbye is third in the programme but sits completely outside the reflective and more somber nature of the other works. Crisply danced and light-hearted in the extreme, this is a chance for the ballet to be ballet, and is all saccharine smiles, virtuosity and rather ‘twee’ interactions of the boy -meets – girl – girl – gets – boy variety. Lots of elevation and tricky partnering in a very Bournonville style, with much choreographic inspiration seemingly owed to Pineapple Poll, Coppelia, Flower Festival and other classical romps!

Dear Horizon, choreographed by Andrew Simmons opens the programme. Tracy Grant Lord’s design and spectacular hanging dominates the space and evolves as haunting white crosses and fragmented red poppies provide a strong pathway into a dark place of memory. Gareth Farr’s commissioned score is dissonant, desperate, discordant poignant, urgent, confronting and utterly evocative of war and conflict and its effects. The choreography is slow, un-compelling, predictable, austere, and is danced by beautiful ethereal beings somehow ‘untouched’ as Simmons looks to reflect on the human aspects of wartime – the hopelessness, loss and fear.

The Soldiers Mass by Jiri Kylian and made for twelve men premiered at Nederlands Dans Theatre in 1980. Kylian’s own Czech nationality and his response to events that changed the path of Europe and plunged the western world into a time of war and conflict is as relevant and powerful in today’s world where politics still dominate and egos still command decisions that affect the lives of all of us. The music by Bohuslav Martinu drives battalions of bodies forward in unison phrasing that breaks and re-forms and relentlessly moves them to their doom. Unexpected vocabulary erupts from the ranks, and exhaustion, camaraderie and dependency in the worst situation we can imagine is strongly evoked. They are not allowed to rest, and we are not allowed to rest, and all the anguish of lost boys and sons and fathers and the futility of warfare washes in waves over the stage.

Superb craftsmanship and construction, this is a master at work organising space, energy, momentum and challenging everyone. It reminds us that in going to war, mistakes are made again and again, and their dreadful effects are ongoing, and the lesson is not learned. The strength of unison is immense in this work but the strength of each individual dancer is electrifying and terrifying as we reflect on war without boundaries and war still in our world today.

Passchendaele, choreographed by Neil Ieremia with music by Dwayne Bloomfield asks us to focus on one war and Ieremia’s personal reflection on this. For New Zealand, Passchendale was the scene of our heaviest losses, and for us as a nation it sits with Gallipoli as a landmark of nationhood. Ieremia sets his work against the wonderfully strong art of Geoff Tune, and as we see the landscape crumble, the dancers find an imagined space of loss, memories, and relationships. The dance vocabulary is strong with partnering and shared lifts for all and a real breadth of scope that reflected the enormity of the subject. Emotional impact is evident and the vulnerability of both men and women is haunting me still … Passchendale is a work that brings each artistic element together brilliantly and it is impossible to disconnect them. The final knock on the door of the theatre as the telegram boy arrives with the news of death that every family feared engages the audience and our own memories and experiences. Such a small moment but one that brings reality and horror home. This is Ieremia at his best and it is engrossing on every level. My only gripe is that it is running for only twelve minutes, so just a snapshot rather than a fully developed work, which is disappointing.

The lighting for the evening by Jason Morphett is excellent. The dancers are secure and in technical command throughout the evening. It is hard to watch them, young, athletic and with the classical aesthetic very dominant, representing the tragedy and fragility and futility of previous generations of youth lost in war – let us hope that in their own lifetimes, hope holds fast for all of them, and the lessons of the past really have been learnt.

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Comments

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Comments