MY DAD'S BOY

BATS Theatre, The Propeller Stage, 1 Kent Tce, Wellington

26/05/2016 - 04/06/2016

Production Details

A young man writes a play about his father, trying to figure him out.

Is he a good dad? A bad one? Does he even know there’s a difference? When he finds out his girlfriend is expecting though, the writer is faced with fatherhood himself.

With John Landreth, James Russell, and Freya Daly Sadgrove.

Highly Commended Adam NZ Play Award 2016

Winner, ATG Festival Buffalo, NY, 2016

Shortlisted, Playwrights b4 25, 2016

BATS Theatre – Propeller Stage*

26 MAY – 4 JUNE 2016

AT 7pm

$10-20

BOOK TICKETS

Accessibility

*The Propeller Stage is fully wheelchair accessible; please contact the BATS Box Office at least 24 hours in advance if you have accessibility requirements so that appropriate arrangements can be made. Read the BATS Accessibility Policy here

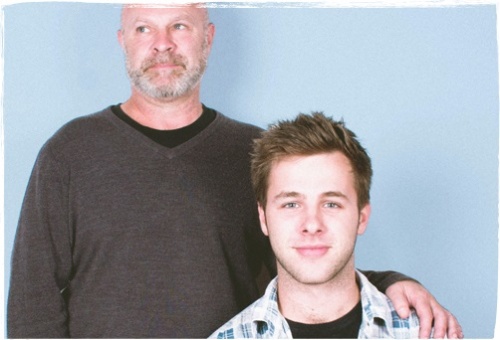

John Landreth

James Russell

Freya Daly Sadgrove.

Theatre ,

Insightful distillation

Review by John Smythe 27th May 2016

This play is so simple, its story so common (initially at least) and its self-referential deconstruction so obvious it may seem surprising that it works so very well. The answer lies in its truth; in how its reductive dramaturgy distils the perspectives of two generations. Plus there are some surprises. Finnius Teppett is clearly a playwright to watch.

To emphasise its consciousness as a theatrical contrivance, director Ryan Knighton has the actors greet their arriving audience. Fair enough.

Despite being publicised as “A young man writes a play about his father, trying to figure him out,” it is called My Dad’s Boy. The playwright character (James Russell), who is the narrative voice, introduces the father character (John Landreth) as “Dad” and himself as “Me”.

He is at that ‘me-centric’ age where his quest may lead him to understand his Dad was, is and will be a person beyond just being his father; the separated husband of his mother. Indeed, as the publicity reveals, the shift in awareness coincides with his facing the prospect of fatherhood himself. And we do soon learn his Dad’s name is Peter.

A series of present interaction and recollection scenes – in 18 stanzas – allow us to share the son’s attempts to “figure him out”. Dad’s story about his moment of rugby glory and his name-dropping John Kirk establishes him as a Kiwi bloke who peaked in the mid-1980s. His work-history and status as a husband are sketched in, and we get an intriguing insight into why he is so reticent about his health.

The son’s relationship with his girlfriend Caitlin comes into the story, as does Peter’s with his co-worker Trish, and his chainsaw. Freya Daly Sadgrove’s splendid playing of them (not the chainsaw) and other roles offers effective counterpoints and sometimes catalysts as the young man’s quest continues.

As ‘Me’ matures, his Dad regresses to dwelling in a student flat and behaving accordingly. The credibility of his being accepted into such a flat, let alone the flatmates throwing a ‘welcome party’, is glossed over and I do think a cogent reason could be revealed.

That said, just when you thought it was all fairly predictable, Helen Clark turns up. I won’t explain how or why but this touch of magic realism does deepen our understanding of what makes Peter tick and Daly Sadgrove renders Ms Clark with alacrity. Her Anton Oliver story is priceless.

John Landreth and James Russell establish a very credible father-son relationship, navigating the time shift between the 18 stanzas with an ease that belies the work they must have put into it.

The young man’s mother remains a cipher and I do think she deserves at least as much representation as Caitlin gets (whose dealing, or not, with the pregnancy issue is a memorable and insightful moment). Mum’s one line is revealing and poignant but we are left wondering what sort of relationship ‘Me’ has had, and now has, with her.

I also feel that ‘Me’ seems to become more passive and bland the more Dad’s flaws come to the fore; the more we identify with and like him. A few more faults could make ‘Me’ more interesting. Maybe more of a self-awareness breakthrough can be extracted from the penultimate confrontation scene where Peter claims his right to be more than just Dad.

And having established the metatheatrical convention up front, I wonder if ‘direct address’ could be utilised more as ‘Me’ and ‘Dad’ wrestle with their choices.

These thoughts I offer because Finnis Teppett has been invited to workshop his play in the USA later this year, as part of his prize for winning the College (i.e. university) section of the 2016 Against the Grain Festival.

It is always a special pleasure to engage with a new play soon after its birth. My Dad’s Boy is well with visiting now and I will observe its progress with interest.

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Comments