Doubt - a parable

Circa One, Circa Theatre, 1 Taranaki St, Waterfront, Wellington

10/02/2007 - 10/03/2007

Production Details

By John Patrick Shanley

Directed by Sue Rider

Designed by NICOLE COSGROVE

Lighting Design by PHILLIP DEXTER

Original Music by GARETH FARR

“Have you ever held a position in an argument past the point of comfort?

Have you ever defended a way of life you were on the verge of exhausting?

That’s an interesting moment.

For a playwright, it’s the beginning of an idea … I started with a title: DOUBT.”

– John Patrick Shanley

Winner of the Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 2005, and a grand slam of Broadway theatre awards, Shanley’s Doubt is a brilliant new play set in a Catholic school in the Bronx in 1964, where four strikingly individual people become entangled in the search for truth.

Leavened with crackling wit, Doubt is a taut drama of ideas posing as a gripping mystery. Capturing nearly every best play award in 2005, Doubt managed to achieve must-see status during its feted Broadway run and represented a return to the spotlight for Shanley, best known for his Oscar-winning screenplay, Moonstruck.

Wellington audiences now have a chance to see this extraordinary play.

CAST

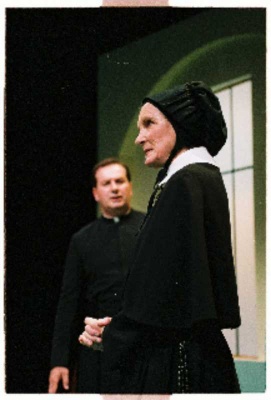

Father Flynn - SIMON FERRY

Sister Aloysius - HELEN MOULDER

Sister James - ANGELA GREEN

Mrs Muller - TANEA HEKE

PRODUCTION TEAM

Stage Manager - Barbara Donnelly

Technical Operator - Marcus McShane

Costume construction - Coralee Hare

Set Construction - Petar Petrovich

Publicity - Claire Treloar

Graphic Design - Rose Miller, Parlour

Photography - Stephen A'Court

House Manager - Suzanne Blackburn

Front of House - Linda Wilson

Theatre ,

1 hr 30 mins, no interval

Tight, enthralling drama

Review by Eleanor Bishop 07th Mar 2007

When a play is marketed as the winner of the 2005 Pulitzer Prize for Drama, and its subtitle is “a parable”, it’s not hard to feel a sense of duty to get the wider point. However, Doubt also functions as cracking good piece of theatre.

The pleasure is in the mystery so I won’t reveal the entire story. Set in a Catholic Church and school in the Bronx, New York, 1964, Sister Aloysius (the brilliant Helen Moulder) is suspicious of Father Flynn (Simon Ferry). For her, “innocence can only be wisdom in world without evil”, and convinced of Father Flynn’s guilt, but without substantial proof, she makes it her mission to bring him down.

But are her accusations real or imagined? Is it her dislike of his progressive teaching methods, and belief that the clergy should be more accessible to the parish? Or is she acting on gut instinct, and belief in her “certainty”?

The writing is succinct – the scenes flow back and forth, allowing us only enough insight into these characters to keep us hooked, but not revealing the absolute “truth”. Rider’s direction is taut, making great use of the triangular acting space, as Father Flynn speaks directly to the audience as if we were his students, or the congregation, drawing us in with his wit and affability. The acting is strong from all four actors, with Shanley’s sly language enabling each actor to hint at their character’s hidden motivations.

At its core, Doubt is a moral tale about how far we’ll go for the truth, what sacrifices we’ll make and at what human cost. It’s an important enough tale on its own, but it’s that irksome little word in the programme – “a parable” that ensures the audience will think about the wider significance of the events in the play.

Shanley writes in the tradition of Miller’s The Crucible – which used a literal seventeenth century witch hunt in America, to comment on McCarthy’s techniques to root out communist in the 1950s. Doubt was written in 2004 and Shanley presumably aims to comment on 9/11 and the Iraq War – i.e. the lengths Americans will go to, to rid themselves of the unease and doubt gripping the nation post 9/11. Doubt seems to argue that the determination to have a resolution, a result, has overtaken the fact that the perceived “enemy” may be innocent.

Doubt shows us that the structures of Arthur Miller and Tennessee Williams, applied to new subject matter and seen through a modern viewpoint can be just as powerful as they were in their own time. This tight, enthralling drama is well worth seeing.

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Terrific play

Review by Lynn Freeman 22nd Feb 2007

Faith and doubt needn’t be contradictory, in fact, argues Father Flynn, doubt can be a powerful aid to the faithful. But in John Patrick Shanley’s Pulitzer Prize winning play, the doubt Sister Aloysius feels either puts her on the side of the angels or makes her a dangerously misguided zealot. You choose.

That’s the great strength of the script, that the audience must make up its own mind.

The story is set in a Catholic church and school in the Bronx in New York, in 1964. The nuns teach on one side of the grounds, the male hierarchy is on the other, and seldom do the two meet – certainly never unsupervised. The school has its first Coloured student, who’s having a hard time of it.

It is a terrific script, but even so it could be butchered by a poor production. Sue Rider and her cast all live up to the promise it offers a strong director and cast.

Simon Ferry confidently walks that fine line between being charismatic and just a little too affable as Father Flynn, a priest who’s trying to make the Catholic church more modern and more in touch with the community it is supposed to serve.

Helen Moulder as the stern featured, righteous Sister Aloysius, makes sure we see the nun’s humanity alongside her intolerance for change, her resentment towards the male-dominated Church system and her deeply held suspicions about the Father’s behaviour towards the lonely Coloured student.

As the Sister mounts a relentless crusade to get the Father out of the school, based not on evidence but instinct, he asks her where her compassion is. "Not where you can get at it," she replies.

As the young and naïve Sister James, Angela Green represents the loss of innocence, as she is drawn unwillingly into the bitter clash between the Father and Sister, the new and old church, and what she believes to be right and what she is told she must do.

Tanea Heke has only one scene as the student’s mother, but she makes a strong impression as a coloured woman determined to help her son out of a violent home situation and into a better life through education.

Nicole Cosgrove’s set uses the stage to full advantage, with a tall pulpit to one side, and Sister Aloysius’ plain cream and green offices to the other. A meeting place lies in between, with a dead thorny rose at its heart.

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Comments

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Tantalising mystery mixes the moral and political

Review by Laurie Atkinson [Reproduced with permission of Fairfax Media] 12th Feb 2007

Lauded with over 20 awards including a Pulitzer Prize John Patrick Shanley’s Doubt: a Parable is a surprisingly old-fashioned, Rattiganesque play and is at one level a tantalizing mystery, set in a Catholic school in the Bronx of 1964, about whether a Catholic priest is a pedophile or not, and at another level it is a parable that raises questions about the current moral and political climate in the United States.

The play starts with the popular, progressive priest Father Flynn, who teaches at the school and is inspired by John XXIII and Vatican II, giving a sermon in which he says, "There are those of you in church today who know exactly the crisis of faith I describe. I want to say to you: Doubt can be a bond as powerful and sustaining as certainty. When you are lost, you are not alone."

He is implacably opposed by the principal, the formidable Sister Aloysius, who is utterly convinced of the priest’s guilt even though she has no evidence other than the 12 year-old boy and only black student in the Irish/Italian school drank some communion wine. She will even step outside the confines of the Church, and worse, to achieve her ends "though doors should shut behind me."

Shanley cleverly keeps the audience from taking sides. There’s something admirable in Sister Aloysius’s determination to preserve her beliefs and standards at all costs but we also see her advising a young, enthusiastic teacher, Sister James, to stop seeing good in everyone and to be more skeptical, even though we realize she is destroying her buoyant spirit. Then the boy’s mother is interviewed and again Shanley upsets the audience’s expectations by the reaction the mother makes to the possibility that her son has been abused.

The play, for me, is too self-consciously rigged, particularly in the final moment of the play, for debate to be entirely successful. Shanley has said that "I don’t want to write only plays that Democrats would like. I want Democrats and Republicans to be able to have an interesting conversation afterwards." He also has Father Flynn say, "The truth makes for a bad sermon. It tends to be confusing and have no clear conclusion."

Nicole Cosgrove’s three-piece transverse setting (pulpit/garden/principal’s office) neatly allows the play under Sue Rider’s unfussy direction to move smoothly and efficiently for its uninterrupted 90 minutes.

Tanea Heke as Mrs. Muller, the young boy’s mother, makes a strong impression in her vital scene, while Angela Green captures both the enthusiasm of Sister James as well as the spiritual desolation with an excellent performance. As Father Flynn Simon Ferry has the eager-beaver likeability of the slightly portly young priest off to a T and when challenged on his relationship with the boy he is suitably enigmatic.

Helen Moulder’s Sister Aloysius has the necessary cold, steely determination of one who knows she is right and she conveys this with whiplash authority and in the final confrontation with Father Flynn she and Simon Ferry burn up the stage.

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Comments

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

The doubtful nature of faith

Review by John Smythe 12th Feb 2007

While this is a different production from the Centrepoint Doubt I reviewed last year, with Sue Rider directing this time and a different design team, three of the four roles are played by the same three actors.

John Patrick Shanley’s Doubt is as much, if not more, about the nature of faith than doubt. Or perhaps it is best described as being about the doubtful nature of faith. And, as with the key content of the Father Flynn sermons that punctuate the play, it is a parable.

When one notes (as Rider does in the programme) that Doubt – which premiered off-Broadway at the Manhattan Theatre Club in November 2004 – was written in response to 9/11 and the US decision to go to war, in the apparent conviction that weapons of mass destruction existed and that violence could be cured with violence, it takes on greater meaning.

Just as Arthur Miller’s The Crucible dramatised the Salem witch hunts in order to question the actions of Senator Joseph McCarthy’s Un-American Activities Committee, so Shanley’s Doubt takes us to the Bronx in 1964 (just after the assassination of President Kennedy) to consider an incident that may or may not have happened in a Roman Catholic school run by the Sisters of Charity. Indeed, as Rider also points out, the black bonnet habits of the Sisters clearly echo the puritan setting of Miller’s play. (A quick Google suggests this style is not entrenched in the order, but the visual point the Nicole Cosgrove-designed habits make is entirely valid for the purpose.)

It is also important to note Doubt‘s clear relevance to the Christchurch Crèche case, which stands as the Kiwi outbreak of a world-wide epidemic, all provoked – as I understand it – by a particular faith in a certain style of counselling.

“In the pursuit of wrong doing, one steps away from God,” declares the school’s principal, Sister Aloysius, in justifying her use of an outright lie to reveal what she still believes to be the truth. Father Flynn is the focus of her fear and loathing, itself rooted in a fear of change and more enlightened teaching methods. And he happily invents stories which he presents as ‘true’ by way of making his point in a sermon. Such is the nature of parables. And plays.

Sister Aloysius (Helen Moulder) has a feeling in her dry old bones that something’s awry in the relationship between her teacher of religion and physical education, Father Flynn (Simon Ferry), and Donald Muller (aged 12, unseen), the school’s first and only Afro-American pupil. When young Sister James (Angela Green), who became a novice before she ‘became a woman’, is asked to look for evidence, her innocent joy in her vocation and her love of teaching history are demolished.

But it’s not a simplistic goodies versus baddies story. The unconditional love Mrs Muller (Tanea Heke) has for her son – whom she has to protect from a violent father who also fears difference and change – leads to a surprising and confronting take on what’s best for him, no matter what. Real life in the mean streets meets the idealism of convent life in a very provocative way.

Also, the patriarchal protectiveness of institutionalised Catholicism with its strict hierarchies of communication is, perversely, a major component in making us think twice (at least) about whether there could be more to Father Flynn than meets the eye.

My concern with the Centrepoint production was that, apart from Angela Green as Sister James, the actors had not fully inhabited their roles as whole human beings, contenting themselves – it seemed – with being relatively objective mouthpieces for the differing points of view. This no longer applies at Circa.

Simon Ferry’s Father Flynn is fully imbued with the commitment to his vocation and the systems that support it, that make him both admirable, vulnerable and finally questionable. Tanea Heke likewise has real blood coursing through her veins as she embodies Mrs Muller’s upright pride and steely determination to keep her eye on the main chance for her boy.

With an impressive lightness of being, Angela Green’s Sister James powerfully reprises and refreshes the fallibility of innocence, the vulnerability of passion and the courage of her own convictions – in the face of strong challenges – that make her such an indispensable character.

As the newcomer in this cast, Helen Moulder is at her acerbic best while finding dimensions of pragmatism, wisdom, humanity and compassion in the deeply entrenched position taken by Sister Aloysius.

Nicole Cosgrove’s sharp triangular thrust stage set with a pulpit in the blackness beyond, lit by Phillip Dexter, works well although it doesn’t quite give us the other half of the audience as a live backdrop. My only quibble with Sue Rider’s otherwise sound direction is that she doesn’t take advantage of the thrust space, instead having characters in committed dialogue facing more to the front than each other. It looks contrived and dilutes the sense of authenticity.

The play itself runs at around 90 minutes but don’t expect to dash off and hook into something else straight away. I’m not the first to observe that a whole other act may well follow in the shape of the post-play discussion it will doubtless provoke. Both times I have seen Doubt I have been quite clear on the question of Father Flynn’s guilt or innocence, only to find others think – and/or feel – quite differently. And if you then step back from the parable to consider its relevance to the war in Iraq … Give yourselves time. That part of it is free, well worth it and very much to the point.

_______________________________

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Comments

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Comments