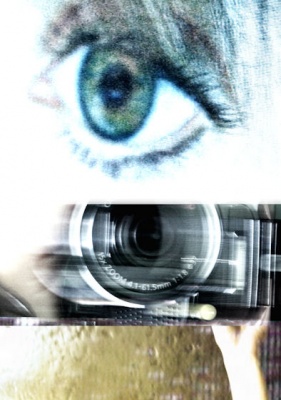

Girl with a Movie Camera

TAPAC Theatre, Western Springs, Auckland

02/03/2011 - 05/03/2011

Q Theatre Loft, 305 Queen St, Auckland

07/10/2011 - 08/10/2011

24/03/2012 - 25/03/2012

Production Details

Rehearsal directors 2011: Natalie Dowd, Dannielle Chandler

Vocal coach 2011: Georgia Wood

Set design: Adrian McNaught

IT/Technical/Artistic Support: Rene Burton

Lighting 2011: Dayle Burgess

Motion capture/Maya artist and additional post-production: Shea Melville

50 minutes

Highly accomplished multimedia show

Review by Jonathan W. Marshall 26th Mar 2012

Girl With a Movie Camera is a highly accomplished multi-media show from recent graduates of the Auckland University of Technology dance program, choreographed by Jennifer Nikolai and with projection from Andrew Denton.

The piece takes Dziga Vertov’s landmark montage study of the contemporary urban environment, Man with a Movie Camera (1929), as a jumping off point for various visual and choreographic sketches. The dancers quote out loud assorted passages from Vertov’s writings, but in truth, the relationship between the material performed and Vertov’s own work is mostly relatively slight.

Denton’s imagery for example includes almost no rapid montage from one camera perspective to another. Vertov’s central idea of montage-synthesis, which he shared with Sergei Eisenstein, entailed the almost organic linking of different objects and forms through their rapid sequential replay on the cinema screen. Denton does not perform such a combination of shots, and the choreography itself rarely echoes this concept of synthesis.

In the end though, this is relatively unimportant. Despite the title, Girl With a Movie Camera is not an actual reinterpretation of Vertov as dance. Rather, Nikolai and Denton use several of Vertov’s key concerns as motifs around which the material is built.

These themes include the framing of vision by a lens, the speed and pace of the modern world, and especially its means of transportation (cars, trains, motorways), the transformation of bodies into machines or cogs within a larger mechanism, and the experience of modernity as an almost ecstatic one of transformation and of power.

The mise en scène takes the form of two screens at the back onto which imagery is projected, or behind which the dancers move in order to cast shadows across the surface. A narrow passage divides the screens, leaving a horizontal strip of stage at the front for further interactions.

The initial framing of the movement is somewhat clunky. Nikolai and Denton work hard to make the screens themselves the focus of much of this early attention, and so quite a lot of action gets sandwiched between them this awkward interstitial space.

Soon enough though the forestage comes into play, and more complicated choreographic forms arise. The score is essentially a jukebox of various techno and electroclash musics (Peaches, LCD Sound System) interspersed with contemporary chamber music in the lyrical repetitive mode of Philip Glass (though actually by the Vitamin String Quartet). This renders the performance highly episodic, each sequence distinguished by its own musical and rhythmic pattern, typically with a short period of silence and darkness between to emphasis the conceptual and scenographic discontinuity between sections.

The material is linked, but each section starts from a fresh palette (quite the opposite of Vertov). The feel then is often that of a highly accomplished popular dance-floor, and although some of the choreographic material is drawn from Contact Improvisation (falls, climbing on top of each other, and catches), the overall style is largely that of generalised modern dance after Cunningham with a tendency towards jazz-ballet and other modes which synthesise popular dance with the precise, accented articulation of the trained dancer. Sharp angles about the joints giving a slightly robotic look to action comes to dominate as the piece progresses.

Projected sequences often alternate with those of the live performers, notably a sequence showing them in cropped close ups about the face and eyes as they gaze out the windows of Auckland’s trains, or another sequence where brightly coloured virtual armatures of dancers (produced using motion capture technology) weave and spin about a boundless black space, as the planes on which they are dancing also shift, come forward, recede, or twirl about a central pivot.

Perhaps the most striking sequence is where the projections offer the viewpoints of a number of cameras as these are carried by the moving dancers. Images are inverted, great arcs are described, and other confusing yet invigorating distortions of space are offered. As these films play out overhead, a lone dancer comes on stage holding a video camera, and it becomes clear that she is recreating the positions that she executed when the video was produced. Other dancers gradually arrive, and this ghostly, previously empty or haunted space becomes literally populated. The visual and experiential or kinaesthetic difference between what the audience can now literally see in the dancers, and the sense of swirl and movement which the camera eye presents on screen, now becomes intense and quite exhilarating.

I have seen many, many dance companies struggling with cumbersome digital technologies as the artists strive to project imagery produced by an on-stage camera onto screens whilst they dance. Nikolai and Denton however remind us that since dancers are expert at recreating movement that they have already executed, there is absolutely no reason not to integrate pre-recorded visuals with live performers. Indeed, precisely such a strategy, again, rather than synthesising and combining different perspectives, highlights the differences between these positions in a way which is quite fascinating. In this respect, Girl With a Movie Camera approaches Eisenstein’s concept of dialectical montage: a use of space and material which rather than simply blending things together, sets them off as distinct but related entities.

Although the title at first seems somewhat sexist and belittling — why not Woman With a Movie Camera? — there is a manner in which youth, and specifically feminine youth seems deeply tied to this aesthetic. An early sequence which shows the performers running through shopping centres and staring out from escalators could come from a girl teen film since the 1990s (though the celebration of glittery consumption and the buying of things is absent here). The dance-floor style choreography also imparts a sense of young women exalting in the various experiences which contemporary popular culture offers. The musical sources — notably an ironically cute piece by Japanese girl band Shonen Knife — enhances this quality.

In this sense, ironically, Nikolai and Denton are very close to Vertov, since one of the most striking elements in his own film is the mapping of urban forms and shapes onto the youthful female body. In Man With a Movie Camera, skyscrapers and office blocks become parts of the naked body of a woman disrobing in her urban apartment. The sexual, life-affirming power and the increasingly fit, toned and taut shapes of the so-called New Women, the modern girl and the flappers of the 1920s seemed to epitomise the very essence of modern culture for Vertov and his peers.

Whilst Nikolai and Denton do not present such a cohesive thesis, their production is open to such a reading, and for this it is all the richer.

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

A sweet homage to Vertov’s work

Review by Jack Gray 08th Oct 2011

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Comments

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

On critiquing, this show and contemporary dance in general

Review by Lexie Matheson ONZM 14th Mar 2011

Walter Kerr, reviewing John Van Druten’s I am a Camera in 1951, summed up his experience in three memorable words: ‘Me no Leica.’ I am a Camera went on to become Cabaret and a great hit. Reviewers are not always right. I like to think that, had Kerr experienced Girl with a Movie Camera he would have, as I did, Leica’d it a lot!

Let’s be perfectly clear. Art should be liberating and, since Girl with a Movie Camera is most certainly art and I was most certainly liberated by it, I must say that I am a fan of Jennifer Nikolai the person, the teacher, the philosopher, the coffee-drinking buddy. Of Jennifer Nikolai, in fact, I am inordinately fond. We work together, have the same employer and have been known, on occasion, she adds blushing, to share a bottle of wine – in the company of our wonderful partners, of course. This needed to be said as partners also come into this reflection and we leave them out at our peril. Just as Vertov’s wife Elizaveta Svilova edited his work, so Nikolai’s husband Andrew Denton is integral to Girl with a Movie Camera, but more of that later …

So there, now you know.

Not that knowing someone and respecting them should be reason to misunderstand, under-estimate, or over-value their work. Nor should it mean, in a country the size of New Zealand where the arts are universally undervalued and quality practitioners are sparse, that we should not review each other’s work where appropriate and be seen to be objective about it. It’s a fact of life and we should get used to it. It’s better, surely, to have an informed and detailed critique than unrestrained praise from the illiterate and uninformed. Reviews are, after all, not just fodder for the artist or quotes for the marketing team but should also provide an educated source of critical comment, knowledge and information for the general public and, dare it be said, an historical record as well.

As reviewers we should also get used to the fact that some artists feel they have the right to lambast reviewers for their opinions and do so with alacrity. I have, on occasion, done so myself and felt much better for it. “There, that’ll show him,” I have thought whilst at the same time realising that, apart from dissipating pique, I have achieved nothing.

Back in the day my work was often reviewed by Paul Bushnell, not always favourably, but I grew to view with satisfaction the knowledge that he would review what I had created. I didn’t always agree with him but I did grow to respect that he would always be honest and, when necessary, ruthlessly so. Through Paul’s informed and intelligent observations my work grew. He had that happy knack of sensing when I was cheating and had the courage to say so. Bravo Paul, thank you for your integrity, particularly as I am aware that others were less enamoured of your candour and certainly felt free to say so.

I endeavour, always, to emulate your integrity.

Girl with a Movie Camera is listed as ‘a multi-media dance/theatre piece with live and video performance, choreographed by Jennifer Nikolai and dancers, with video direction by Andrew Denton and performed by dancers from the AUT Dance Company’, and so it was.

It should be noted that, among the dancers of the AUT Dance Company, was Nikolai herself. She was unheralded, un-named, indistinguishable (though not undistinguished, oh, dear no!) a hoofer just like everyone else and this was oh so appropriate, particularly as this work followed the line of it antecedent and might have been cast, anonymously, from the Moscow telephone directory.

Performed in the main theatre space at TAPAC where the cavernous nature of the deep stage provides a great starting point for any dance work, Girl with a Movie Camera also benefited from the height as the staging consisted of two rectangular white fabric ‘drops’ which served as both projection monitors and, when back lit, perfect display screens for a range of beautifully executed live cinematic silhouettes. These silhouettes, it must be noted, had been rehearsed with exquisite care and the placement of light sources was such that a surreal power relationship between dancer and a single-minded camera tripod was able to be vibrantly explored in three dimensions with no loss of clarity.

While a mere 40 minutes long, Girl with a Movie Camera, through its use of a wide range of contemporary recording and projection devices interfaced with rich physical imagery and pulsating movement, was proof that it is the quality rather than the length of a piece that is important and that shortish and complete can be as satisfying as anything else. If you’re talking value for money this was certainly it!

Never one to take the easy route, Nikolai and her team set themselves a supremely serious task, namely “to build on Dziga Vertov’s application of film montage, his theories on ‘kino-pravda’ and his seminal film Man with a Movie Camerainto a platform for dancers to develop themes into performance, in a live and recorded format. Video images and performances contrast or complement each other in an exchange of media and mediums. It is a conversation between ideas, images, and performance in search of new meaning.”

So says the press release and, quite surprisingly, this is what actually occurred. Surprisingly because press releases are often simply opportunities to advertise in ways that, while giving a sincere indication of intent, seldom deliver what is promised. Girl with a Movie Camera delivered what was promised.

Kino-pravda or ‘film-truth’ was developed by Vertov in the 1920s as a tool for filming the everyday and the mundane and, through this, reaching a deeper truth. His style is functional and economic and he filmed in markets, bars, public places and mostly without permission. As his documentary series evolved he was more and more frequently called an ‘idiot’ and told he was ‘insane’.

History recalls Vertov differently and credits him with first use of techniques such as fast and slow motion, freeze frames, split screens, tracking shots, scenes shown backwards and odd things with animation. Many of these techniques are evident in both Nikolai’s choreography and in Denton’s moving imagery almost all of which was shot in Auckland. Particularly evocative were a fast-filmed day in Auckland and a fine robotic sequence performed by the company. Worthy of note here – since robotic dance has been around forever – was the freshness of ideas and the rhetoric of the physical vocabulary used in this set.

In fact the dance vocabulary throughout had a freshness and spontaneity that only comes from a freedom to discover and a delight in recreating the spontaneity of those discoveries. Not that the rehearsal machinery showed at all, quite the opposite.

Also impressive was the confidence – and the assurance – of the dancers. This was quality work danced unemotively, but not without emotion, by dancers who clearly knew they were riding a winner and who were pretty damned happy to be there. These performers were right on top of their game!

Often contemporary dance dissolves into a mishmash of previously learned (and seen) vocabulary and this is most often evident when the work lacks structure. This isn’t limited to non-linear works and it’s fair to say that, because of the nature of Vertov’s original, Nikolai’s work is less than linear. In fact, at times it seems almost intentionally episodic and expressionistic but, while so being, it never lacks metaphoric and impressionistic linkages that enable the viewer to make important reflective connections that are unique to them. Rather like ‘my random impression’ versus ‘your expressionistic reflection’, which is clever because the viewer can only ever be right about what they are consuming. Smart art, that is!

Andrew Denton’s moving images are sublime. Using some of Vertov’s repertoire of trickery Denton makes the world his own and we are constantly gob-smacked by what he achieves. He quite literally takes our breath away and when the dancers interact choreographically with the imagery, gems of memory are there for the taking. I’ve long thought that the exit moment of any work of art, that moment when you emotionally depart, is the most critical because when engagement leaves off memory begins and the reality of the encounter immediately becomes something else. Real art doesn’t just exist in the experiential flash but also in the subsequent moments of refection and memory both of which can be exclusive and dissimilar. Denton and Nikolai provide ample exit moments within the composition and we are constantly put in the vein of reflecting and remembering even before the whole opus is done and dusted.

Perhaps the most exciting aspect of Girl with a Movie Camera is that it’s not just some ‘this happened and then this happened next’ narrative. This is multi-media performance art at its finest, doubly exciting in that it’s reminiscent of nobody else, yet remains firmly locked in its contemporary dance oeuvre all the same. I tried to find reference points – Cunningham, Balanchine, Wright, Parmenter – but none would fit. This was Nikolai/Denton, pure and simple.

Yet, having said all the above and labelled this ‘art’, it must also be said that Girl With a Movie Camera wasn’t all po-faced and serious. It was also funny, witty, charming, idiosyncratic and oft-times just plain odd. It was also raw, intelligent, profound and passionate. It was all about us. About Auckland. And them. Yes, us and them. And accessible, always, always accessible.

Whilst Nikolai has choreographed and staged extensively in Vancouver this is her first choreographic outing in New Zealand and we would like to see many more. Like a seed planted and tenderly nurtured, Girl With a Movie Camera has blossomed as expected, spoken as was intended and will now remain tucked away in the memory along with those two words we are hot-wired to exclaim when our humanity is laid bare: ‘bravo’ and ‘more’.

I’m adding this text of a piece by Laurie Anderson which always, for me, encapsulates contemporary dance:

Walking and Falling – Laurie Anderson

I wanted you.

And I was looking for you.

But I couldn’t find you.

I wanted you.

And I was looking for you all day.

But I couldn’t find you.

I couldn’t find you.

You’re walking.

And you don’t always realize it, but you’re always falling.

With each step you fall forward slightly.

And then catch yourself from falling.

Over and over, you’re falling.

And then catching yourself from falling.

And this is how you can be walking and falling at the same time.

_______________________________

For more production details, click on the title above. Go to Home page to see other Reviews, recent Comments and Forum postings (under Chat Back), and News.

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Comments

Jack Gray March 15th, 2011

Wish I saw it. Nice review Lexie and good work Jennifer.

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Inspired by Vertov ... and thought-provoking

Review by Julia Barry 06th Mar 2011

_______________________________

For more production details, click on the title above. Go to Home page to see other Reviews, recent Comments and Forum postings (under Chat Back), and News.

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Comments

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Comments