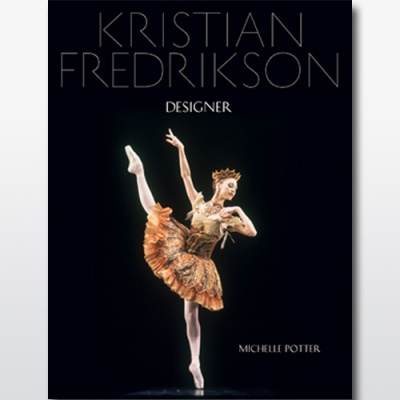

Kristian Fredrikson: Designer

04/10/2020 - 30/09/2021

Production Details

Multi-discipline designer Kristian Fredrikson was an extraordinary influence in Australian Dance, Opera and Drama.

His collaborations with Graeme Murphy saw scenes of unleashed imagination, breathtaking beauty and impeccable craftsmanship, pulsing with human emotion. Memories of Kristian’s sets and costumes for Sheherazade, Daphnis and Chloe, An Evening, The Selfish Giant, After Venice, Late Afternoon of a Faun, King Roger, Beauty and the Beast and later stagings of Poppy, are his legacy to us all.

This book examines the life and career of acclaimed designer for the theatre, Kristian Fredrikson (1940-2005). Fredrikson worked across theatrical genres including in theatre, dance, opera, and film and television.

Born in Wellington, New Zealand, Fredrikson began his design career working with a small, amateur operetta company in Wellington. He then went on to establish a major, five decade-long career in Australia, returning to New Zealand on occasions to design for opera and ballet.

During the 1970s Fredrikson worked extensively with Melbourne Theatre Company where he met the then-emerging Australian choreographer Graeme Murphy. This was to be a turning point in his life and in 1979 he made his first work for Murphy’s Sydney Dance Company, a mysterious and exotic Sheherazade. Those years were also when he began an association with the Australian Opera, which included a production of Lucrezia Borgia in which Dame Joan Sutherland sang the lead.

In the 1980s, Fredrikson was persuaded to return to New Zealand to design works for Royal New Zealand Ballet.

It was the ballet he admired above all and the book examines two New Zealand productions, two Australian ones, and one (his final work) in Houston, Texas. ‘I was willing to die for my art,’ Fredrikson said. And he did, while the Houston Swan Lake still in preparation.

Kristian is a recipient of four Erik Design Awards and won prestigious Green Room Awards for After Venice (Sydney Dance Company – 1985), King Roger (1991), Turandot (1991), The Nutcracker (1992), Salome (1993), Swan Lake (2002) and an AFI award for Undercover. Kristian also received a Penguin Award for The Shiralee (1988). In 1999 Kristian received the Australian Dance Award for Services to Dance.

- Hardback | 240 pages

- 221 x 280 x 27mm | 1,240g

- 04 Oct 2020

- Melbourne Books

- Melbourne, VIC, Australia

- English

- 1925556506

- 9781925556506

Book , Dance ,

A major theatre designer of his generation

Review by Dr Ian Lochhead 19th Sep 2020

Stage names are so commonplace in the world of ballet that they hardly require comment; only the readers of encyclopaedias tend to know the names Edris Stannus, Margaret Hookham and Roberta Ficker, but their adopted names, Ninette de Valois, Margot Fonteyn and Suzanne Farrell, are known around the world. Although theatre designers are more likely to employ their birth names, there are notable exceptions; Lev Samoylovich Rosenberg and Varvara Jmoudsky became world famous as Léon Bakst and Barbara Karinska. It should thus be no surprise that the New Zealand designer, Kristian Fredrikson, began life in Petone in 1940 as Frederick John Sams. Fredrikson’s identity as a designer appears to have evolved during his late teens and early twenties as he moved from an early career in journalism to his true metier of stage designer. First the spelling of Frederick shifted to the more European ‘Fredrik’ as seen in the signature on a drawing dating from around 1960 that shows a Maori gathering. Prominent in the foreground of this pen and ink study is a young man with a full facial moko. Was the model for this figure the artist himself? In spite of the moko, there is a definite similarity to photographs of the young Fredrikson, suggesting that he was also exploring what it meant to be a New Zealander.

Fredrikson’s drawing, now in the National Library of Australia, is reproduced in Michelle Potter’s carefully researched, lavishly illustrated and handsomely produced study of his career as a stage designer in New Zealand, Australia and the United States. Potter traces the gradual transition of his artistic identity as the surname Sams was replaced by Fredrikson on a press pass of 1962, until finally, with his first substantial group of costume designs for a Wellington production of a Night In Venice, he emerged as Kristian Fredrickson. What prompted him to adopt a name that suggested a Scandinavian origin? Was he simply trying to make a connection with a world as far away as possible from the mundane reality of Wellington in the early 1960s, or was he paying a more specific tribute? By the early 1960s, the Swedish theatre director and filmmaker, Ingmar Bergman, was at the height of his fame, but it is tempting to think that Fredrikson’s inspiration may have been found closer to home in the example of the Dane, Poul Gnatt, the founding director of the New Zealand Ballet. It is certainly clear that Frederikson aspired to design for the ballet from early in his career and the 1963 New Zealand tour by the recently founded Australian Ballet Company provided him with a crucial opportunity and the incentive to relocate to Australia. His costume designs for the Australian Ballet’s 1964 production of Aurora’s Wedding were followed by over a decade of work in Melbourne with the Union Theatre Repertory Company, later the Melbourne Theatre Company. There, his career developed rapidly and the diversity of the company’s repertoire was an ideal training ground for the young designer. From the beginning, the element of fantasy that is a consistent element of Fredrikson’s designs was evident, but this was increasingly disciplined by his detailed knowledge of the history of fashion and his ability to combine different fabrics, colours and textures to achieve ravishing effects.

By the time he returned to work for the Australian Ballet in 1972 for its production of Sir Frederick Ashton’s Cinderella, he had worked on productions for the New Zealand Ballet, the Melbourne Ballet and West Australian Ballet. His 1979 costumes and sets for the Australian Ballet’s Coppelia have proved particularly enduring and, when they were borrowed by the Royal New Zealand Ballet in 2014, they looked as fresh as when first designed. Of particular importance for the development of Fredrikson’s career was his long working relationship with the choreographer, Graeme Murphy, first at the Sydney Dance Company and later at the Australian Ballet. His designs for the Sydney Dance Company’s 1979 production of Shéhérazade were inspired by the art of the Vienna Secession and in particular the works of Gustav Klimt. One of the particular pleasures of Potter’s book is the inclusion of full-page illustrations of Fredrikson’s designs with their many annotations for the makers clearly legible. A characteristic note on one of the Shéhérazade drawings reads, ‘Important – save any gold (2m.) fabric left over – difficult, if not impossible to procure. I have more, but waste not want not!’

One of the mysteries of Fredrikson’s art is how he developed his encyclopaedic knowledge of the materials and techniques of costume design. His brief period at Wellington’s Technical College seems inadequate as an explanation for his mastery of his craft and there does not seem to have been any opportunity during his early years working in Melbourne to account for this, other than his innate talent and ability to learn on the job. A photograph of Fredrikson in 2000 by Peter Brew-Bevan shows him at home, surrounded by shelves filled to overflowing with books and CDs. He looks out at us with one hand covering half his face, as if to say ‘I will show you this much, but no more’, and there is a sense that not only is he protecting his privacy but also the secrets of his art. Regrettably, space was not found for this portrait in Potter’s book, although it does appear in Valerie Lawson’s 2019 history of ballet in Australia, Dancing Under The Southern Skies.

Throughout his career, Fredrikson continued to return to New Zealand to work for the Royal New Zealand Ballet and, importantly for New Zealand readers, these productions are given a chapter of their own. They included Swan Lake, Russell Kerr’s Peter Pan and Gray Veredon’s A Servant of Two Masters. The latter production incorporated an ingenious set consisting of stretched silks through which the cast could make rapid entrances and exits, an essential requirement of a plot that depended on the illusion of characters being in two different places at the same time. The other advantage of this set was that for touring it could be packed away into just two suitcases.

A final chapter looks at Fredrikson’s designs for what he considered to be the ultimate ballet, Swan Lake. For the Royal New Zealand Ballet he worked on two productions, Harry Haythorne’s in 1985 and Russell Kerr’s in 1996, the latter restaged to celebrate the company’s sixtieth anniversary in 2013. An illustration from that production, showing Abigail Boyle as the Queen, illustrates the way in which Fredrikson’s designs contributed to the character being portrayed. The sumptuous gown, with panels of gold around the skirt and the sleeves built up from sections of fabric of contrasting colours, shimmers like a Byzantine mosaic. Robed like this, how could you feel anything other than regal? The positive impact of Fredrikson’s designs on performers as well as audiences is confirmed by Kerry-Anne Gilberd, who wore the scintillating black tutu he conceived for Odile in the 1985 production. Fredrikson claimed that the lace he had personally selected in New York for this unique costume was a fragment left over from a garment made for Greta Garbo in the 1920s. There is no way of knowing whether this was actually the case, or if this was another example of Fredrikson’s myth making? Either way, the perceived association with one of the most beautiful women of the twentieth century could only have contributed to Gilberd’s characterisation and added to the allure of Odile.

Fredrikson was also the designer of both sets and costumes for Graeme Murphy’s reimagined Swan Lake for the Australian Ballet in 2002, a production that has been toured internationally. Whatever the successes or failures of this production as a whole, Fredrikson’s designs gave it a unique look. Odette’s flowing wedding dress with swirling train, used to such dramatic effect in Act One, became the signature image for the production. As with his collaboration with Murphy in their earlier reimagining of the Australian Ballet’s Nutcracker: The Story of Clara, Fredrikson was closely involved with every aspect of the production including the development of the scenario. One revealing detail illustrates how, with a single deft stroke, he could add a level of depth to a character. Odette’s wedding dress initially appears pure white but as she moves, its grey underskirt is revealed. While this is consistent with the monochromatic palette of the design as a whole, it also introduces an unexpected colouristic accent that underscores the ambiguous situation that this bride finds herself in.

There have been few studies of theatre designers in either Australia or New Zealand, and Michelle Potter’s book is a very welcome addition to the growing literature on theatre and dance in this part of the world. There is little doubt that had Kristian Fredrikson been based in London, Paris, or New York, he would have been regarded as one of the major theatre designers of his generation. It is our good fortune that he chose to base himself in our part of the world and we owe it to his memory to preserve the productions that have become such an important part of our shared theatre history. Revivals of his Swan Lake or The Servant of Two Masters by the Royal New Zealand Ballet would be a cause for celebration. Which imaginative festival director will seize the opportunity to mark the twentieth anniversary of his death in 2025 to stage a commemorative Fredrikson season, bringing together acclaimed productions from both sides of the Tasman?

Inevitably, the wear and tear of performance means that costumes have a limited life and it is important that companies that have Fredrikson designs in their wardrobes treat them with the care befitting their historical and artistic importance. The Dowse Art Museum already houses an important collection of Fredrikson’s costumes for the Royal New Zealand Ballet and this should surely be augmented in due course. Collections such as these will provide the basis for the theatre histories of tomorrow and Michelle Potter’s book is an object lesson in the vital importance of preserving performing arts collections. Without the Fredrikson archive in the National Library of Australia in Canberra and the holdings of the Australian Performing Arts Collection at Melbourne’s Arts Centre, as well as those at the Dowse Museum in Lower Hutt, it would have been virtually impossible to recount Fredrikson’s career with anything like the comprehensiveness that Potter has achieved. This is an important book which will give renewed pleasure to everyone who has enjoyed Fredrikson productions in the past and which will open the eyes of those who have yet to discover the magic of his very personal vision.

Kristian Fredrikson: Designer is available in New Zealand for $70.00 from Unity Books, Wellington, http://www.unitybooksonline.co.nz

or directly from Melbourne Books, https://www.melbournebooks.com.au for AU$59.95 plus postage.

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Comments