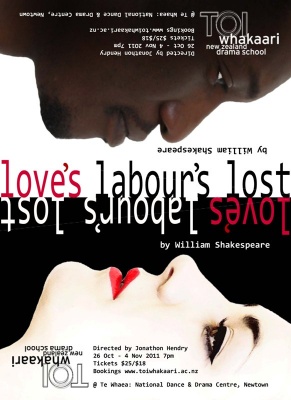

Love’s Labour’s Lost

Te Whaea National Dance and Drama Centre, 11 Hutchison Rd, Newtown, Wellington

26/10/2011 - 04/11/2011

Production Details

One of Shakespeare’s greatest comedies

The King of Navarre and his three young friends have devoted themselves to study when they are surprised by the Princess of France and her sexy entourage. How can you study when you have got love in your mind?

Love’s Labour’s Lostis one of Shakespeare’s greatest comedies. It is a romantic romp containing some of his most sparkling language – many words which he invented for this play, and which still remain in circulation – and crammed with jokes, disguise and hilarious confusion. It is also the only play that remains of the two that he wrote as companion pieces: Love’s Labour’s Lost and Love’s Labour’s Won, which has been lost (!) – and director Jonathon Hendry is having some fun with it this year, in a gender-defying production in which the audience gets to choose who will play each role.

It is also the grand Toi Whakaari season finale and the graduation production for the Year 3 Acting students. In total over 34 Toi students have pulled the stops out with the set, costumes, lighting and design – as well as the actors themselves – to create a spectacular showcase of the best of the performing arts in New Zealand.

Director Jonathon Hendry is a Shakespeare expert. An Artistic Fellow of Shakespeare’s Globe in London, he has played many Shakespeare roles including Richard III, Macbeth, Iago, Jaques and Malvolio and is much in demand for Shakespeare workshops for students, teachers and professional actors around New Zealand.He is also an award winning actor, and has a distinguished directing career with ATC, Silo, Downstage, Circa, Centrepoint and BATS; and as a teacher he has headed the acting department at Unitec as well as teaching at many other institutions around New Zealand including Massey and Victoria. He has been Associate Director and Head of Acting at Toi Whakaari since 2007.

From the team that brought you last year’s celebrated musical Company at the Museum Hotel, Love’s Labour’s Lost promises to be a hilarious exploration of the fun, confusion and zaniness of love.

When: Wednesday 26 October – Friday 4 November (no show Sunday 30 Oct)

(26, 27, 28, 29, 31 Oct, 1, 2, 3, 4 Nov)

Time: 7pm

Where: Te Whaea: National Dance & Drama Centre, 11 Hutchison Road, Newtown, Wellington

Tickets: $25 / $18 concession

Bookings: 04 381 9253 / www.toiwhakaari.ac.nz

CAST

Tawanda Manyimo Ferdinand (King of Navarre) Dumaine

Phoebe Hurst Berowne Longaville

Leroy Lakamu Berowne Longaville

Ana Corbett Princess of France Maria

Te Rina Thompson Princess of France Maria

Sophie Kendrick Rosaline Katharine

Hayley Sproull Rosaline Katharine

Elliot Wrightson Boyet (Lord attending to the Princess)

Chris Parker Costard (a country swain)

Adrian Hooke Don Adriano de Armardo Dull

(a fantastical Spaniard) (a constable)

Victoria Abbott Don Adriano de Armardo Dull

(a fantastical Spaniard) (a constable)

Emma Fenton Moth Jaquenetta

(his page, a boy) (a dairymaid)

Leon Wadham Moth Jaquenetta

(his page, a boy) (a dairymaid)

Catherine Croft Sister Natalie (a nun)

A Guest Actor Monsieur Marcade (a messenger)

Other parts played by company

A delight of dichotomies

Review by John Smythe 05th Nov 2011

Following the final night of this Jonathon Hendry-directed Toi Whakaari: NZ Drama School graduation production, it is the inherent dichotomies that resonate richly, for me.

As each audience enters the traverse space we are separated by gender, consistent with the ‘never the twain shall meet’ premise of the play (the vow made by the King of Navarre and his three male friends to devote themselves to study for three years, abjuring all contact with women, is tested when the Princess of France and her female friends arrive …) yet a number of the male roles are played by female actors.

Indeed the two standout performances in a consistently strong ensemble are Phoebe Hurst’s focused, articulate and deep-feeling Berowne, and Victoria Abbott’s diminutively dynamic, ‘r’-rolling and proudly posturing ‘fantastical Spaniard’ Don Adriano de Armardo.

While we are encouraged to bond with our own gender group in opposition of the other, it is the other which forms the backdrop to our viewing of the play. Yet after interval, although we are free to mix – given the wannabe studious men had long since broken their vows to stay separate – almost everyone returns to their segregated seats. Does that denote a preference for being with our own kind or for looking at the others?

The director’s note tells us that the principle of using games of chance to allocate 12 of the 16 roles between six pairs of actors allows them “to discover the play anew with the audience”. Yet our understanding and enjoyment is certainly aided by the clarity and confidence of the four actors who always play the same roles: Elliot Wrightson (a Bowie-esque Boyet), Chris Parker (a classically clowning Costard), Catherine Croft (a subtly detailed Sister Natalie; substituted for Sir Nathaniel, a curate) and Lily Greenslade (an imperious and tippling Holofernes, here a headmistress rather than a schoolmaster).

Recreating a play anew in each performance – experiencing the action as if for the first time – is a basic tenet of the acting craft. So while I don’t really buy that rationale for adding a nervous energy zing to a show (such as is inevitable with improv), I do see the value of sharing the roles more equitably around a graduating group of actors.

Helen Sims’ review of the opening night suggests some of the cast were not fully prepared for the role they scored. As it turns out much of the casting was the same on the final night and by then everyone was fully equal to the task.

I’ve been unable to find out who played which of the four French women then, and given they operate as a tight group most of the time, and wear the same frocks regardless of their character name on the night, I imagine the challenge of remembering which lines are whose has been greater for them. I am bemused that little attention was given to a sense of upper-class refinement in the voices of these courtly ladies. Nevertheless, on this last night Ana Corbett gives a majestic account of the Princess of France while Te Rina Thompson (Maria), Sophie Kendrick (Rosaline) and Hayley Sproull (Katharine) delightfully delineate their respective roles.

Twanda Manyimo’s King Ferdinand, Haley Brown’s Dumain and Leroy Lakamu’s Longaville complete the quartet of ‘epic fail’ scholars who soon discover that (to quote Webster), “what is denied is desired”; that the thing you resist is the thing that persists.

Cast as they were on opening night, Leon Wadham plays a flighty Moth, page boy to Don Adriano de Armardo, and Emma Fenton is wonderfully earthy, physical and vocal as the dairymaid Jaquenetta, eloquently beloved of the Don while Costard simply gets on with the job of sating their mutual lust. (If anyone saw Wadham as Jaquenetta and Fenton as Moth, or Ferdinand /Dumaine and Berowne /Longaville with alternate casting, feel free to add your comments below).

Adrian Hooke’s Keystone Cop-like Constable Dull is as tightly contained as I imagine his Don was florid and showy and he adds splendidly to the atmosphere and festivities with his original compositions and piano playing.

Costume Stylist Kaarin Macaulay happily allows the French women colour in fashion (despite their being in mourning for the Princess’s father) while constraining the would-be student males in black and white. Don Adriano de Armardo’s intrepid adventurer costume is a triumph.

The traverse staging with steeply raked seating on either side makes the stage floor itself a feature which designer Theo Wijnisma resolves with a superb rendition of the core dichotomy: regimented geometric squares at one end succumbing in the middle to a flow of freely-expressed flourishes. The library shelves at one end and dressing room with make-up mirrors at the other complete an inspired set design.

Jonathon Hendry and his cast and crew have infused the whole production with the directly connected-with-the-audience spirit he tuned into at the Globe in London, which may be credited with liberating Shakespeare from fusty academe and elitist adoration, and returning him to the people.

A final note on dichotomies: the sense of a beautifully balanced and bound ensemble is offset by an awareness that this group will now go their separate ways into a profession bereft of theatre companies of actors contracted for whole seasons (although, to be fair, scoring a continuing role in the TV series or serial, or a Sir Peter Jackson epic film shoot, would reconnect them with that ‘family’ feel).

But as part of their major 3rd-year performance work, each individual has also developed a solo piece (reviewed here as Groups A & B and Groups C & D), to equip them with the capacity to make their own work instead of waiting to be asked. They have to be ready for anything – and are.

The acting class of 2011 has a lot to offer us all and I look forward to their getting or making the opportunities to put their undoubted skills into practice.

– – – – – – – – –

Regarding the lost companion piece, Love’s Labour’s Won (also written in the mid 1590s), I am attracted to the theory (advanced some decades ago by Sir Tyrone Guthrie) that when he was developing his major tragedies for the rising merchant classes, Shakespeare needed something populist for his loyal audience, so he resurrected his abandoned script, revised it and called it All’s Well That Ends Well. I know this is a disputed claim but cannot recall the argument. Anyone?

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Energy, fun and some inconsistency

Review by Helen Sims 28th Oct 2011

The battle of the sexes begins early in the Toi Whakaari graduation show, Love’s Labour’s Lost. The decision to tackle one of Shakespeare’s lesser known comedies provides a welcome opportunity to see a rarely-staged work performed by a large cast. As the audience is welcomed into the theatre by the 3rd year acting class, women and men are instructed to face off on opposite sides of the promenade stage.

The play is textually rich, although the plot is paper thin. It commences with the King of Navarre securing the agreement of three of his friends to abjure the comforts of the flesh in order to pursue the enrichment of the mind. The King signs a decree that prohibits love-making between men and women.

Unsurprisingly the hoi polloi quickly run into trouble under the new edict, especially the country swain Costard, who is competing with the fantastical Spaniard Don Amardo for the affections of a randy wench Jaquenetta. The King and his entourage abandon their oath and books following the arrival of the Princess of France and her attendants.

Somehow everyone escapes trouble, although no one really gets what they want, and there is a bizarre play within the play performed.

Before the play proper begins the actors mix with the audience and recruit them to assist in determining the roles they are to play for the night. Carrying through the theme of split identities, most of the cast have prepared the role of two characters. Games of chance (the flip of a coin, paper-scissors-rock or a card draw) determine which character the actor will play tonight. It also aims to ensure the show will be kept fresh, as the combination of which actor plays which character will be different each night.

Jonathan Hendry’s Director’s Note observes that the plays would have been originally performed with more of a sense of ‘liveness’ than they are now, with short rehearsal periods and on-stage improvisation.

The device works well to ensure a ‘live’ dynamic, but is bound to falter if even one actor isn’t as prepared or comfortable with his or her chance-allotted role as the rest. Unfortunately on opening night this was the case for Tawanda Manyimo, who seemed unsettled in the crucial role of Ferdinand, King of Navarre. Other characters seemed a little underdeveloped, or tended more to caricature than full characterisation.

Bucking this trend for me was Phoebe Hurst, who as the quick-witted and sceptical Berowne has some of the longest and most difficult passages of text. She appeared fully in command of her lines and delivered a spirited performance. The colourful ladies of France (Ana Corbett, Te Rina Thompson, Sophie Kendrick and Hayley Sproull) were a tight unit, although cues and volume were an issue in the first half.

The commoners are uniformly entertaining, with Moth (Leon Wadham) drawing a laugh at almost every line he delivered and Victoria Abbott and Adrian Hooke displaying some excellent physical theatre skills as Dull and Don Armardo respectively (these two roles double and I would go back just to see these actors play the other role).

It seemed like the emphasis was on energy, fun and allowing the actors to exhibit the range of skills they have developed during their time at drama school, in particular song and music. This did lead to some inconsistency in style and at times it was clear that communicating the sense of the text or plot points was not the focus. At half time I overhead many people wondering what on earth was happening, which was not assisted by general problems with audibility.

In the second half the devices marry with the text better, and the comedic lines are delivered with punch. I just about choked when the Spaniard emphatically stated that the King dallies with his excrement!

The show is exuberant and colourful. It is well aided by the excellence of the set design (by Theo Wijnsma) and costumes (Kaarin Macauley). The spaces of masculine court and feminine garden are both clearly delineated and blended, as are the backstage and onstage spaces. The entire theatre space as cleverly used, with actors popping up in a number of unexpected places.

The colourful dresses of the French ladies were a highlight for me, although I do have to question the wisdom of the ladies being shod in wedges, which leads to un-ladylike clumping. I also loved the outfitting of Boyet, who looked like a Shakespearean era Billy Idol.

Despite the undeniable talent of the graduating acting class and designers, not all of the experiments in this production come off. The graduation production does, however, offer an opportunity for such experiments in entertainment before the stakes are raised by having to earn a living from their work.

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Comments

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Shakespeare comedy sets a colourful scene

Review by Laurie Atkinson [Reproduced with permission of Fairfax Media] 28th Oct 2011

Love’s Labour’s Lost is the young Shakespeare showing off his abundant poetic gifts. The comedy, full of “taffeta phrases, silken terms precise, three-pil’d hyperboles,” is concerned with four young men of the court of Navarre deciding to forswear “the huge army of the world’s desires”, which means they will see no women, fast one day in seven, and sleep for only three hours a night as they attend to their studies. Then four beautiful young women arrive.

The Toi Whakaari 2011 graduation production is a splendid one to look at. The spacious, colourful setting by Theo Wijnsma incorporates not only a schoolroom, a library and an elegant palace hall but also the actors’ dressing rooms at either end of the transverse stage. The costumes (Kaarin Macaulay) are a riot of colour and a mix of periods and the hats of the ladies of the court are as gloriously overstated as the language.

The comedy is played with verve and a mixture of styles: Dull, a constable becomes a tiny moustachioed Keystone cop, the pedant Holofernes is a bluestocking headmistress, the page Moth a schoolboy in a uniform, while Boyet, a courtier to the Princess, is a swarthy pop singer. Some of these may be different on other nights as only five of the sixteen actors have set roles, the rest are chosen by various means at the start of each performance.

The audience is invited to join in, not only with the choosing of roles (tossing coins) but also with such things as shouting Ole! every time the fantastical Spaniard Don Adriano de Armardo appears (dressed in jodhpurs), and being used as objects to hide behind. The women of the audience sit on one side of the stage, men on the other. After the interval this division deteriorated.

However, for all the fun of the comedy the poetry gets lost. The transverse stage doesn’t help, and neither does the speed and the volume with which it is often shouted, nor some of the action that is carried out behind a speaker. One of Berowne’s speeches is largely lost because of an unnecessary piano accompaniment and one of Holofernes’s speeches is upstaged by the country boy Costard having it away with the dairymaid, despite Dull’s attempts to hide the heated action from us.

Shakespeare’s superb autumnal ending to the play, when reality is brought to bear on the love games, the sterile intellectual gamesmanship, and the brash comedy of the play-within-the play, is captured in the fine singing of the finale but it feels in this production like an add-on rather than an essential part of the play.

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Comments

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Comments