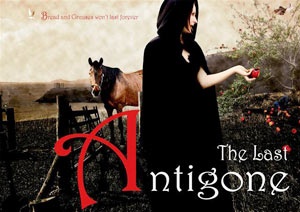

The Last Antigone

Globe Theatre, 104 London St, Dunedin

29/03/2008 - 05/04/2008

Production Details

New Zealand’s Royal Family is in crisis.

After years of prosperity during King Oedipus’s rule, the city of Dunedin is plunged into economic ruin worsened by the scandals and feud inside the royal family. Princess Antigone goes on the road with her disgraced father and begins to learn of life outside the palace walls. Can her youth and new found experience free her city from the curse that her father thought he’d smashed forever?

The last Antigone pays homage to several classic greek plays including

Oedipus Rex by Sophocles

Seven against Thebes by Aeschylus

The Phoenician Women by Euripides

and more significantly:

Oedipus at Colonus by Sophocles

and

Antigone by Sophocles

1hr 30 mins, no interval

Timely reworking of timeless tale

Review by Terry MacTavish 31st Mar 2008

It is certainly a fine augury for Dunedin’s 2008 Fringe Festival that the first production I’ve seen should be a thing of real beauty, bringing together the talents of some boldly creative artists in a work that delights the senses while engaging the mind.

The classic Greek tragedy of Antigone, daughter of the doomed Oedipus, is given stunning new expression by award-winning playwright Tee O’Neill and a strong cast under the direction of Wayne Petcher. O’Neill, currently the William Evans Fellow at Otago University, has adapted The Last Antigone to give it a local flavour for its New Zealand premiere.

This ancient legend has retained its powerful hold on our imaginations, touching our deepest fear, the last taboo, incest. It is the story of Oedipus, who solved the sphinx’s riddle and was hailed a hero, only (unwittingly) to kill his father and marry his mother, thus becoming King of Thebes. Once all is revealed and he has in horror and despair blinded himself, Antigone faithfully follows him into exile. After his death she returns to Thebes to find herself faced by a terrible dilemma: in a rebellion against Creon, now the head of this massively dysfunctional family, both her brothers have been killed. One is buried with all honour, but the other, who fought against Creon, is to lie uncovered on a hillside, to be devoured by dogs and birds of prey. Will Antigone defy Creon’s orders and perform the burial rites, on pain of death? Is the conscience of the individual greater than the law of the state? No wonder the Generals banned Sophocles’ Antigone after they seized power in Greece in 1967.

The Globe Theatre is a shrewd choice of venue, noted as it has been both for its productions of Greek tragedies – Patric Carey once built a small amphitheatre in the garden – and for reinterpretations of them by T.S.Eliot and James K.Baxter.

Inspired work by an extraordinary team, including graphics designer Reatha Kenny and lighting designer Martyn Roberts, sees the stage area stripped bare and painted black, with one slender pole rising from a white floor and mist spilling from the greenroom door. Projected onto the back wall are a series of lovely images, from a romantic view of Larnach’s Castle to idyllic green countryside, and the lighting is gloriously moody and mysterious.

William Campbell’s Greek masks stare sternly from the walls and there is the scent of incense, while the mopork’s night call is answered by the boom of the kakapo.

The costumes, by talented young designer Sam Mitchell, make cleverly quirky use of Dunedin’s beloved Scottish tartan while still appearing cutting-edge fashion. This is essential as O’Neill has updated her royal family to reference the House of Windsor and its attendant media-circus. Princess Antigone, first heard off-stage engaging in some pretty explicit sexual shenanigans, is mobbed on her appearance by a swarm of buzzing paparazzi that she handles with far more aplomb than did either Diana or Fergie. Her glamorous lifestyle is about to be undone, however, by the breaking of the biggest soap-opera scandal of all time.

Antigone, played with fiery spirit as a true heroine by Poppy Haynes, now embarks with her disgraced father on a character-building trek across country, begging for food and learning to live without the privileges of a princess. The tragedy is lightened somewhat unexpectedly as they arrive at Colonus, ‘land beloved of horsemen’, when an actual comic horse arrives. Perhaps it wandered in from a satyr-play? However, this Horse, who harbours a secret crush on not Antigone, but her sister Ismene, is so winningly played by Jackie Shaw that I am convinced every tragedy needs one.

Artists seem to come out of the woodwork in Dunedin – really accomplished designers and actors who just suddenly appear, like these two mature actors with great presence and delectable articulation: Michael Metzger, dignified even in agony as Oedipus/Creon, and serene Amanda Redman lookalike, Emmaline Weaver, as a wonderfully still and controlled Jocasta, whose monologue explaining her marriage to her teenage son lingers in the memory.

But the cast altogether displays great style, with Hollie Sutton (Ismene) and Jimboy (Polyneices) suitable foils for their stronger sister, Erica Newlands as an original Tiresias, and most of all the Chorus of Wyeth Chalmers, Katie Hayes and Adrian Wood, who usually appear as wise commentators. The Chorus are most enjoyable, however, as a rabble of paparazzi behind the impeccable Natalie Milne, a suavely conniving reporter thrusting out her mic to challenge Warren Chambers, the palace’s equally suave spin doctor.

O’Neill has made the most of these opportunities to satirise the lifestyle of those in the public eye, and there is plenty of sharp social commentary, couched in language that echoes the Greek original, like: "Love is only real in its own defeat", to the playful alliteration of: "You’d love me if I were a lawless low-life slag".

Many more elements of a Greek play have been retained, from the long philosophical speeches framed by stychomythia, to the role of the Messenger. Most effective though, are the graceful rituals, reminding us of Greek Theatre’s origins in religious celebrations. Director Petcher has made imaginative use of space, choreographing dreamlike ritualised movement for the funeral rites, as Antigone defies the law and invites her own death.

The legend of Antigone, who stands for the rights of the individual conscience against the state, is timeless, hence any reworking should prove timely. The Last Antigone turns the rich potential of the original into gripping theatre for today, as Antigone is hailed as ‘the People’s Princess’ and urged, "Tell Creon ‘No’ and topple the king!" Like that other princess, she will not go quietly. Cathartic, stirring stuff. But as events in Tibet remind us, fortunately there will never be a last Antigone – somehow the human spirit always finds the courage to fight for truth and freedom.

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Comments