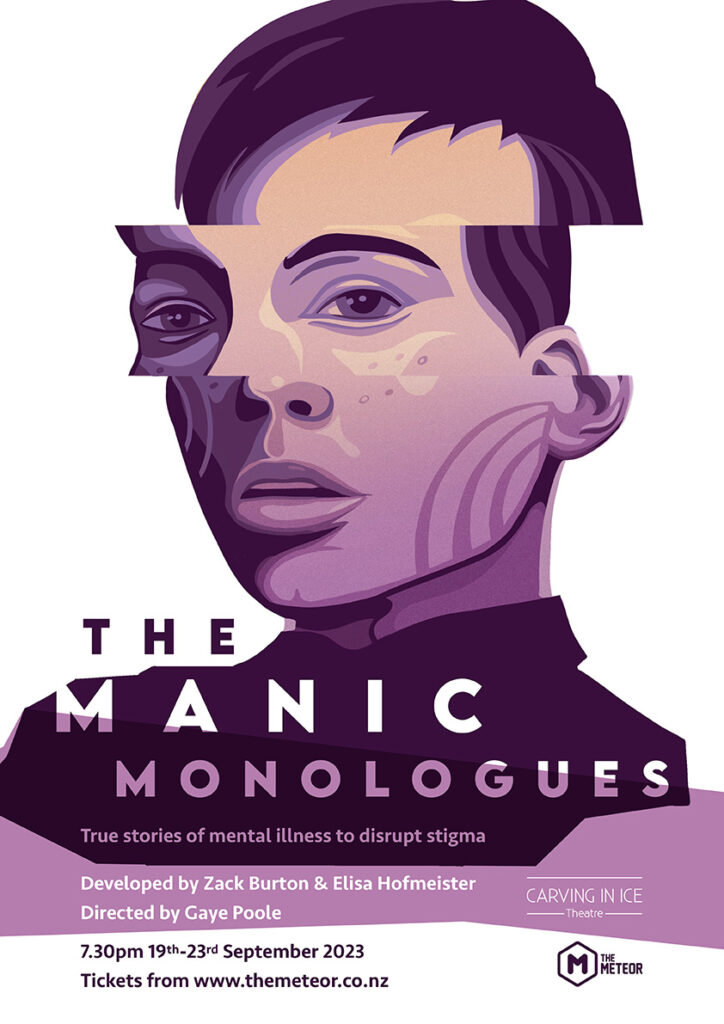

The Manic Monologues

Meteor Theatre, 1 Victoria Street, Hamilton

19/09/2023 - 23/09/2023

Production Details

Created by Zachary Burton and Elisa Hofmeister.

Director: Gaye Poole

Carving in Ice Theatre

“The Manic Monologues: true stories of mental illness to disrupt stigma” showcases captivating stories from those touched by mental illness. The diverse narratives challenge assumptions about what it means to live with a mental health condition. Each monologue explores a different aspect of mental illness. The true stories are from people diagnosed with mental health conditions, the family and friends, and mental health professionals.

7.30pm

19 – 23 September, 2023.

The Meteor Theatre, 1 Victoria Street, Hamilton.

$20 unwaged; $25 waged.

themeteor.co.nz/event/the-manic-monologues/

Cast:

Antony Aiono, Yurika Arai, Danny Bailey, Nick Bourchier, Julianne Boyle, Kathleen Christian, Mandy Faulkner, Libbie Gillard, Nick Hall, Liam Hinton, Simon Howie, Brad Jackson, David Lumsden, Conor Maxwell, Missy Mooney, Georgia Pollock, Fiona Sneyd, Janine Swainson, Sara Young.

Production manager: Gaye Poole

Stage manager: Missy Mooney

Lighting & sound operator: Hannah Mooney

Graphic designer: Pauly B

Theatre ,

Approx 95 minutes including a 15 minute interval

Has an important place in stoking conversations about mental health and fostering empathy

Review by D.A. Taylor 22nd Sep 2023

Discretion advised: Contains themes relating to mental illness and suicide.

Documentary theatre – and in particular, verbatim theatre – comes with the baggage of truth. The genre, built on testimony, records, newspapers and so on, tends to connect with audiences in a way that the more obviously constructed realities of plays may not, since it is made of real people and real experiences. In the case of The Manic Monologues, we have the lived experiences of mental health and illness brought to life.

It’s appropriate that Carving in Ice presents The Manic Monologues during Mental Health Awareness Week here in Aotearoa New Zealand. Nineteen Kirikiriroa Hamilton theatre stalwarts explore different aspects of mental illnesses, all true stories from people diagnosed with mental health conditions, their family and friends, and mental health professionals.

To understand this play, we need to start with a backstory repeated in virtually every resource you’ll find online about The Manic Monologues. Forgive my echo. Zachary Burton had a psychotic break while studying for his PhD at Stanford University. In 2017, Burton and his then-partner Elisa Hofmeister went out to collect stories of mental illness in order to destigmatise conversations about mental health and illness. As a Washington Post article notes in 2019, Burton wanted his Monologues to be to this generation what The Vagina Monologues was in 1996 – disruptive, conversation-starting, taboo-shaking, urgent.

And rightly so. Mental Health statistics are appalling, in developed and developing countries. But only when we are prepared to confront the issues can we work to resolve them, and help people like me (and our friends, families and whanau) affected by mental illness.

Those with long memories will remember The Keys are in the Margarine that toured to The Meteor in 2015, promoting a message of dementia awareness through verbatim theatre. Since then, director Gaye Poole has also brought us, among other Carving in Ice shows, the original Life Music in 2016 (about, well, music), and Hush (about family violence) in 2020. Rounding off this trio for Carving in Ice is The Manic Monologues, that takes us through various dimensions and experiences of mental illness including OCD, bipolar disorder and mania, depression, PTSD, anxiety, psychosis, all tempered with a poignant sense of understanding our heroes: the surviving, the coping, the growing.

The message is important, and I think shows like The Manic Monologues need to be seen to reduce stigma, start conversations about mental health and recognise symptoms that might signal someone needs to reach out for help. This is a social play that draws awareness to a massive issue that faces us. Should you go and see it for these reasons? Yes. Carving in Ice deserve kudos for staging it and doing so with tact and grace, as well as providing resources for the audience to engage with mental health professionals, stationing a representative of the Centre 401 Trust Te Whare Whaa Rau Ma Tahi in the foyer, and coordinating support people from Yellow Brick Road, K’aute Pasifika and other local services to attend each performance. Ka pai.

But documentary shows like this have a strange kind of armour – one strengthened by the traits of the genre. The Manic Monologues makes no apologies for its lack of plot or narrative, and nor should it; it’s about themes and ideas, after all. The writing, we’re reminded, is built on that ever-flexible ‘truth’. What we have left to interrogate might include the text itself. For verbatim theatre, the script – assembled from direct quotes – is largely unassailable, since it belongs in part to the original speakers; for Manic Monologues, which falls into the broader documentary genre, it’s clear that there’s a fair amount of poetic licence at play, but that also means it feels more telling than showing. So, after the indulgence of the above, this is where we can finally sink our teeth in.

To my ear, the most successful pieces are the ones that don’t spell out the illness at the centre, but instead offer symptoms. Standouts include ‘Back to the Corner’ with Nick Bourchier’s lonely bed-mover reflecting on what it means to be adult while locked down at his parents’ home, Mandy Faulkner recounting medication’s side effects in ‘Tardive Dyskinesia’, and Yurika Arai wrestling between spiritual ecstasy and diagnosis in ‘Seeing Spirits’. These are the more innovative works, breaking from the more explanatory formula in other pieces, and offering a fresh glimpse into the subject of mental illness. These also happen to be among the stronger performances, with Bourchier in particular giving a career best. The more telling episodes tend to be heavy with diagnoses and over explanation, careful to make sure no one in the audience misses the message. But when it comes to awareness, subtlety isn’t the point.

We also find all the monologues addressing the same points: mental illness is difficult for the people it affects, and when we address that, we help lift the stigma. No one in this show monologues about policy change or sending funding in the right direction – both of which would have a material impact on mental health statistics. So, by all means, start a conversation with your friends and whanau, and make sure they reach help when they need it. But then put pressure on politicians to make change happen.

Naturally, the staging is simple enough: three chairs, the occasional desk or table, a darts board in the first scene. Words and performances fill the space the best they can. We arrive, finally, at the only thing that we can really interrogate with a show like this: the characterisations themselves, and how well our cast bring to life these monologues.

With 19 Carving in Ice regulars to witness across 22 scenes, the night offers a chance to see a wide gamut of ages, experiences, stories, and levels of embodiment.

The performances vary in quality, all united by commitment and clear compassion from the cast. Many are strong and reliably done, engaging and intelligent. A few deliveries feel a little too familiar, however, like they haven’t evolved far enough from those first read-throughs and have been brought to the stage before characters had a chance to take root despite rehearsals starting in February. That might be intentional, with the actors given licence to ‘be themselves’. But it sometimes feels a little same-same as other performances by these Carving in Ice regulars, ultimately leaving me underwhelmed at times.

Having said that, Antony Aiono is a fresh and too-brief breeze in the fourth scene with ‘It Takes a Village’, taking the audience – as only he can – from glee to damp eyes in the space of a breath. I’m grateful he makes a second appearance in the second half with ‘Religion and OCD’ and goes deeper into a character rationalising the safety of habits.

Georgia Pollock in ‘Meditating My Way to Liberation’ and Missy Mooney in ‘Bipolar Boyfriend’ need to be singled out for related reasons. Given longer monologues to dive into, both Pollock and Mooney imbue their characters – one trying to meditate away the pains of life, the other recounting a manic ex – with organic senses of purpose and life. It’s not just that they’re both high energy pieces, but there’s also a real sense of embodiment at play that has me convinced that these characters exist off the stage and will continue to when the season closes.

Likewise, Kathleen Christian as a mother reflecting on a depressive low and a suicide attempt has a powerful sense of ache, though I do struggle to catch all the lines. And there’s something refreshing and considered about the way Libbie Gillard rages about stress, and I look forward to seeing more of their work on the stage.

The night closes with a longer piece delivered by Sara Young. ‘My Father’s Legacy’ illustrates the leaps made in understanding of mental illness across a few generations. It’s a strong message to leave the audience with: let’s break the stigma and be vulnerable with each other as we address mental illness. We have a long way to go yet, and this show has a place in getting us where we need to be.

Shortcomings aside, The Manic Monologues has an important place in stoking conversations about mental health and fostering empathy, and Carving in Ice deserve recognition for their thoughtful, compassionate presentation of this work. Behind the armour, there are glimpses of an intelligent, skilled play, bolstered by a few strong performances. It is not as skilled or confronting as it could be but will find a sympathetic audience that will rally behind its message, regardless of the quality of the writing or performance. Considering the nature of this show, that is something of a given. But if it generates conversations – and, we hope, some policy change – then it has done some good.

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Comments