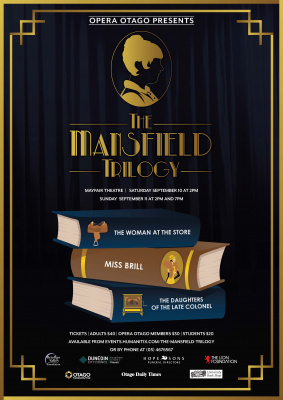

THE MANSFIELD TRILOGY

Mayfair Theatre, 100 King Edward Street, Kensington, Dunedin

10/09/2022 - 11/09/2022

Production Details

Based on short stories by Katherine Mansfield

Dorothy Buchanan (composer)

Jeremy Commons (Libretto)

Directors: Clare Adams, Kim Morgan, Lisa Warrington

Presented by Opera Otago

Otago Opera presents The Mansfield Trilogy – adapted from three stories by Katherine Mansfield.

The Woman at the Store:

Mayfair Theatre, Dunedin

Sat 10 Sept – Sun 11 Sept 2022

2pm (Sat); 2pm & 7pm (Sun)

$40; $30; $20

BOOK or phone 03 4676567

CASTS:

Miss Brill:

Director: Clare Adams; Musical Director: Sandra Crawshaw

Cellist: Jack Moyer

- Miss Brill - Olivia Pike

- Middle-aged Man - Kieran Kelly

- His Wife - Erin Connelly-Whyte

- Young Man - Scott Bezett

- His Girlfriend - Jemma Chester

- Ensemble - Blaise and Sarah Barham

The Woman at the Store:

Director: Lisa Warrington; Musical Director: Mark Wigglesworth

- The Woman - Lillian Gibbs

- The Girl - Calla Knudson

- Jo, a Drover - Ben Madden

- Jim, a Drover - Roger Wilson

The Daughters of the Late Colonel:

Director: Kim Morgan; Musical Director: David Burchell

- Miss Josephine Pinner - Erica Paterson

- Miss Constantia Pinner - Emma McClean

- Kate, their Maid - Sarah Hubbard

- The Rev. Mr. Farolles - Frederico Freschi

CREW:

- Prod. Manager/SM - Linda Brewster

- ASM/Props - Christine Wilson

- Publicist/FOH - Jordan Wichman

- Lighting Designer and Technical Operator - Chelsea Guthrie

- Wardrobe - Charmian Smith

- Assist. Wardrobe - Becky Hodson

- Hair/Makeup - Christal Allpress

- Producer/s - Opera Otago Executive Committee

Opera , Theatre ,

The Mansfield Trilogy

Review by Brenda Harwood 19th Sep 2022

Opera Otago returned to the stage at the weekend with an ambitious project in The Mansfield Trilogy, three short operas created by three separate teams, which came together into a satisfying whole.

With music composed by Dorothy Buchanan and libretto by Jeremy Commons, The Mansfield Trilogy adapts three Katherine Mansfield stories for the stage — The Woman at the Store, directed by Lisa Warrington with musical director Mark Wigglesworth, Miss Brill, directed by Clare Adams with musical

director Sandra Crawshaw, and The Daughters of the Late Colonel, directed by Kim Morgan with musical director David Burchell.

Each performance was skilfully done, evoking the tone of the stories, from dark and poignant, to oddly comic. [More]

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

A truly illuminating trilogy

Review by Kate Timms-Dean 18th Sep 2022

These are strange times. I hear people say those words a lot lately. So, we feel like we are in for a special treat, my friend and I, as we arrive at the Mayfair Theatre. We’ve worn Sunday best for the 2pm matinee performance, all shined up for the opera, and are giggling lightheadedly as we cross the road and enter the foyer. After weeks, months, years of hiding away, we feel like naughty children sneaking out without permission

As we take our seats we see an intimate setting on stage: a simple shop floor and a grand piano tucked to the side. The first pianist (Mark Wigglesworth) enters and takes his seat atop the sealed orchestra pit. Neither of us are sure what to expect. We eagerly consume the contents of the programme, beautifully produced and packed with information, as is always the way at the Mayfair.

The Mansfield Trilogy is our repast, showcasing three of the author’s short stories. They were first presented in operatic style in Wellington between 1998 and 2010, with composition by Dorothy Buchanan and libretto by Jeremy Commons. Three stories, three groups of women, three sets of lives drawn together by common themes, common whakapapa. The light these kōrero shine on the lives of women in the early twentieth century is truly illuminating.

First up, ‘The Woman at the Store’ (Director: Lisa Warrington; Musical Director/Pianist: Mark Wigglesworth; published in 1912.)

The comedic entry of the two drovers, Jim (Roger Wilson, reprising his delivery from the original production) and Joe (Benjamin Madden) provides a deceptively soft start to this darkly disturbing story. This veneer is brutally stripped away, piece by piece, stroke by stroke, as we become increasingly aware of an air of strangeness. A shop counter strewn with rotted fruit; a dirty-faced unkempt child (The Girl, Calla Knudson) with staring eyes and grubby shoeless feet speaking gibberish; two men pursuing her mother (The Woman, Lillian Gibbs), cornering and cajoling her to let them stay the night.

As the story progresses, the Woman’s loneliness becomes unmistakable; her husband is gone and her children are buried, all but one. Her daughter, though, is grubby and shoeless, apparently unfed, and playing in the dust and grime on the floor, seemingly forgotten and neglected. The Woman sees her departed family as she stares into the distance, but The Girl seems invisible, ignored. When food is delivered, The Girl does not receive a plate.

The Drovers feel, more than notice, the not-rightness of the scene that becomes more and more obvious until eventually, it is undeniable. The Girl perches on her bed of sacks, birdlike, her eyes wide and strange.

“She shot him in the head and buried him by the river.”

The drovers depart soundlessly, disappearing into the night, leaving loneliness to descend again.

I am disturbed. This is not what I expected. On the surface, I imagined lightness and nostalgia, but I am surprised and not by the emotions I experience.

As the set is remade and a new ensemble of musicians enters, I am caught, reflecting on the lives of my female forebears, feeling a connection to the line of women stretching out behind me.

I was born in 1969, the same year my grandmother turned 70, having been born in 1899. My mother, her daughter, was born in 1934 and her dreams of studying medicine were annihilated in 1952, when her father told her he wouldn’t pay her fees. He couldn’t see anything before her beyond marriage and motherhood.

As children, my sisters and I grew up on stories of the hardships endured by women in those days, without any power or control, forever bound to a man to lead, own, guide, and decide on her behalf. The fear and wrongness of this reality is a theme that has been indelibly stamped across my life.

We were expected to attend university, to take up the opportunities that were denied our matriarchal line since forever. We had a responsibility, to other mother, to all women, to step into the world and take up our equality. This was a birth right that was fought for and gained by women who were never able to enjoy what they had gained.

I ruminate; I am lost in thought as the next story, ‘Miss Brill’ (Director: Clare Adams; Musical Director/Pianist: Sandra Crawshaw), begins. The only props two park benches side by side. Sandra Crawshaw and a cellist (Jack Moyer) are in accompaniment.

Miss Brill (Olivia Pike) enters, takes her seat. This is her seat, every Sunday, she tells us, but now that the weather is getting colder, she has brought her old friend, her fox fur stole with her. She has given him a wee tidy up, shone his eyes and blackened his nose.

As they sit and chat, these two old friends, they watch and bear witness to the tiny slices of people’s lives that they can see from their park bench seat. To Miss Brill, this is her role – to watch, to witness, and to remember. As she sits today, though, she starts to question whether she is needed. Her reality starts to fracture.

Couples pass, (Keiran Kelly and Erin Connelly-Whyte; Scott Bezett and Jemma Chester; Blaise and Sarah Barham), drawing awareness to the solitude of Miss Brill, talking to her fox fur, her only friend. Although in some cases these people pass without a word or warmth between them, they at least have human companionship.

The final couple drives the message home. Miss Brill is old, alone, unloved.

A longer break this time, long enough for a trip downstairs and a drink. There is some time to talk and think, to re-evaluate and draw the links back to the days of our mothers, both working women in the 1950s. Both had taken their chances on careers as Karitane nurses (quite independently – we don’t think they ever met). They both married later in life, which stopped the repeated sotto voce of “on the shelf”. Both had been miserable with their lot as women.

We wander back upstairs for our final theatrical feast: ‘The Daughters of the Late Colonel’ (Director: Kim Morgan; Musical Director/Pianist: David Burchell). I have to say, this one is my favourite. That’s probably because, rather than being women trapped, these are women freed.

Jug (Erica Paterson) and Con (Emma McLean) are mourning the passing of their father, the Colonel, and are struggling with the smallest of decisions. Deciding things has never been their domain, and even the method of cooking their fish puts them in a flap. “What would father say?!”

The gaping trap of a marriage to fill the decision-making void is implied by the actions of the Rev Farolles (Federico Freschi), but the daughters intuitively defer, even though this would be a solid solution. In contrast, Kate, their maid (Sarah Hubbard) dreams that a man will sweep her away and save her from the two tabbies.

The sisters tremble, like frightened deer, their nostrils flickering as they test the air for danger. Their father is dead, but his rules, his presence is still burning bright in their minds. Slowly, slowly, however, the rigorous tightening of the fist of his rules loosens and falls away. Jug and Con breathe; they can decide.

As we leave, descend the stairs, and head out into the bluster and traffic of South Dunedin, I am struck by the relentlessness of time. The death of Queen Elizabeth II last week floats into my mind, the norms she saw hold sway and slowly fall away. Holding hands with the past, remembering and honouring is important, but letting go is also part of life. She played her part in that, as a woman and a queen who served with easy grace and understated integrity, she demonstrated without fuss that women are capable of making decisions, just as well as any man.

My last impression as I close the car door, is the face of Calla Knudson like a baby sparrow, all eyes and pursing lips, her sweet voice warbling, her chin shivering. I fold the memory up and pop it in my pocket, saving the feeling of wonder and trepidation that she triggered.

“Brava,” I whisper to the falling dusk. “Bravissima.”

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Comments

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Comments