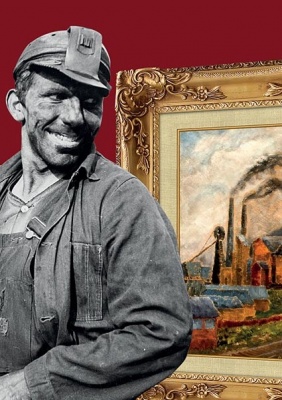

THE PITMEN PAINTERS

Circa One, Circa Theatre, 1 Taranaki St, Waterfront, Wellington

04/10/2014 - 08/11/2014

Production Details

A WONDERFUL PIECE OF THEATRE: COMIC, POIGNANT, STIRRING.

From Tony award-winning writer Lee Hall, best known for Billy Elliot, comes this amazing true story. Since its premiere in 2007, The Pitmen Painters has been hugely successful, receiving rave reviews and sell-out performances in the North East and at the National Theatre in London, enjoying two national UK tours, a transfer to the West End and also to Broadway, New York.

In 1934 the Ashington group of British miners hired a professor to teach an art appreciation evening class. Rapidly abandoning theory in favour of practice, the pitmen began to paint – prolifically, and unexpectedly became art-world sensations!

“Virtually all the events in the play are true,” says Lee Hall, who being Newcastle born and bred is a fellow Geordie. “They really did go to London and hang out with famous artists and their work did attract big collectors. They learned the language of that world.

“Their lives seemed to make a good subject for theatre, a way of investigating some of the problems that culture brings if you’re coming from outside of it, as these guys clearly were. It’s a sort of parable. Of course, having written about miners and ballet, this didn’t seem too big a stretch!”

“The Ashington pitmen were aspirational about high art,” he says. “From when they first heard about the wonders of Cézanne and Henry Moore, they not only felt entitled, but felt a duty to take part in the best that life has to offer in terms of art and culture.”

And they succeeded beyond their wildest dreams. “We made our life into art,” says one of them. “It don’t get better than that.”

For Hall, a great believer in the power of comedy, The Pitmen Painters allows him to make splendid use of the North’s tradition of wry humour. “There is a particular Northern voice, one that understands the absurdities of the world and comes across in a comic way,” he says. “Comedy has to be shared, it’s an expression of communal feeling and I’m making something that people share rather than just expressing myself.

“The most objective thing in theatre is the laugh – it’s almost a physical reaction to your work. It’s a very comforting sound.”

A richly funny, deeply moving and highly entertaining salute to the lives of a group of ordinary men who do extraordinary things, The Pitmen Painters takes you on an unforgettable journey from the depths of the mine to the heights of fame. This is a play that is not to be missed!

“Superb – warm, funny and thought-provoking” – Daily Telegraph

“Ablaze with intellectual vigour, political passion and incendiary emotional energy. A beautiful work of art that everybody should see.” – The Times

★★★★★Best New Play, Evening Standard Award

Circa Theatre. 1 Taranaki Street, Wellington

4th OCTOBER – 8th NOVEMBER

$25 SPECIALS – Friday 3rd October – 8pm, Sunday 5th October – 4pm

AFTER SHOW FORUM – Tuesday 14th October

Performance times: |

Tuesday & Wednesday – 6.30pm

Thursday, Friday, Saturday – 8pm

Sunday – 4pm

Ticket Prices:

Adults – $46; Concessions – $38; Friends of Circa – $33

Under 25s – $25; Groups 6+ – $39

BOOKINGS:

CIRCA THEATRE, 1 Taranaki Street, Wellington

Phone 801 7992 www.circa.co.nz

THE ASHINGTON GROUP

The Ashington Group (Pitmen Painters) unique collection of over 80 of their best paintings are held as part of the permanent exhibitions at Woodhorn Museum near Ashington in Northumberland, UK.

“What they produced was fascinating and if a picture paints a thousand words, these pitmen’s paintings speak more eloquently than any photograph. They captured every aspect of life in and around their mining community, above and below ground, from the scenes around the kitchen table and in the allotment to the dangerous and dirty world of the coal face.”

Today the Ashington Group is acclaimed worldwide, and they have been the subject of TV documentaries on BBC and ITV.

If you would like to find out more about the group:

http://www.experiencewoodhorn.com/the-pitman-painters/

http://www.ashingtongroup.co.uk/home.html

CAST

George Brown: PATRICK DAVIES

Oliver Kilbourn: GUY LANGFORD

Jimmy Floyd: RICHARD DEY

Young Lad: SIMON LEARY

Harry Wilson: PHIL VAUGHAN

Robert Lyon: GAVIN RUTHERFORD

Susan Parks: YAEL GEZENTSVEY

Helen Sutherland: CATHERINE DOWNES

Ben Nicholson: SIMON LEARY

DESIGN TEAM

Set Design JOHN HODGKINS

Lighting Design MARCUS McSHANE

AV and Projections Design JOHANN NORTJE

Costume Design SHEILA HORTON

PRODUCTION TEAM

Stage Manager: Eric Gardiner

Technical Operator: Michael Duggan

Sound: Paul Stent, Ross Jolly

Accent Coach: Hilary Norris

Set construction: John Hodgkins

Set Finishing: Therese Eberhard

Publicity: Claire Treloar

Graphic Design: Rose Miller, Kraftwork Design

Photography: Yael Gezentsvey, Stephen A’Court

House Manager: Suzanne Blackburn

Box Office Manager: Linda Wilson

Mapping the transformative properties of art

Review by John Smythe 06th Oct 2014

Given this based-on-a-true story play involves a bunch of blokes, their tutor, a collector and a life model exploring and debating the notion of ‘art’ in a series of relatively static, dialogue-driven scenes spanning 13 years (1934 to 1947), the phenomenal success of The Pitmen Painters may seem surprising.*

Should we compare it to Yasmina Reza’s Art, produced by Circa in 2000 and also directed by Ross Jolly? Both trade very productively on the deep-set fear most of us have of embarrassing ourselves if we dare to venture an opinion on the good or bad qualities of a given work of art. But Reza was satirising middle-class pretensions with eviscerating wit.

Lee Hall (most famous for scripting Billy Elliot the film and then the musical) extracts a surprising amount of warm humour by mapping the elevation of Britain’s working class from the dark depths of manual labour in the coal mines of northern England to the enlightenment of artistic self-expression. Not as self-indulgence, he emphasises, but as a gift to beholders who will inevitably have their own personal response to each artefact.

If I have a gripe with the script it is that it repeats itself a lot, especially on the ‘eye of the beholder’ point. Indeed, in the second act, Helen Sutherland, the collector, says, “You all just repeat yourselves, saying the same things,” (doing just that right there). “There’s no development.” Not that she has any idea about the realities of their lives, writing off a couple of haunting depictions of pit work as “dreary.”

The set-up is that four pitmen, one wannabe pitman and the local dentist (who was gassed at the Somme so can’t be a miner) have enrolled in a WEA evening class on Art Appreciation – for something to do of an evening. Little is revealed about their contemporary home lives, although we get some backstory about a couple of them having left school at 10 or 11 to work down the pits because the family needed the extra income. And two have never seen a woman naked.

What stops it from being a dramatised lecture at times is the very different characters and what their verbal exchanges reveal about the ‘journey’ each has embarked upon. I am undecided as to whether it is the script or this production and these performances that give more development to some characters than others.

There are some sequences, on opening night, where the characters seem more like mouthpieces for what Lee Hall wants to say rather than distinct individuals discovering themselves, each other and their artistic ‘voices’. This may change as the season settles.

Patrick Davies epitomises the buttoned-up stickler for rules in George Brown, always resistant to the unexpected, change or stepping out beyond the known. Richard Dey is the invariably loud, lumpish and dogmatic Jimmy Floyd whose choice of subject in his paintings is not what you’d expect.

Eighty years ago a mining town dentist was a tradesman like any other and Harry Wilson, robustly personified by Phil Vaughan, is a rampant Marxist to boot. As the ‘runt of the litter’, denied a name other than Young Lad, trying to find his place in the world, Simon Leary is always worth watching while the others are mouthing off. When he at last finds something that makes him feel wanted, his innocence and the shocked reactions of the older men – combined with our greater awareness of what is in store – has a powerful impact imbued with tragedy.

The painter given the biggest story arc is Oliver Kilbourn, arguably the highest achiever of the Ashington Group. While the depictions of George, Jimmy and Harry could be described as more impressionistic, Guy Langford embodies Oliver’s journey utterly, drawing us into his very real experience and compelling our empathy. His story captures the essential dilemma of individualism versus collectivism which lies at the heart of our social values and political choices.

The catalyst for the Group’s evolution is Robert Lyon, Master of Painting at Kings College in Newcastle but not (yet) a professor, much to George’s disgust. It is he who realises his lectures on the Renaissance will have little effect and the best way for these men to learn to appreciate art will be to do it themselves. Gavin Rutherford captures his journey from fish-out-of-water to somewhat envious observer of their achievements with astute aplomb.

It is Robert who hires life model Susan Parks, intriguingly played by Yael Gezentsvey. Given there are no life drawings or paintings is the Ashington Group paintings available on line, I am tempted to think this is a device Lee Hall has invented to dramatise the limits of human experience imposed on single men in small mining communities, and to give women a voice in the discourse.

Robert also brings in art collector (and heiress to the P&O Line fortunes) Helen Sutherland, to view and evaluate the paintings. By being true to each moment, Catherine Downes keeps us intrigued and guessing as to whether Helen has any true expertise or simply the power to decree by dint of her dosh, as she endows with her favours – or not – and attempts to take Oliver under her wing.

Simon Leary gets to contrast his lost Young Lad with successful upper-class artist Ben Nicholson, adept at playing the game to remain in Helen’s favour and feed the beast that is the ever-fickle world of art ‘consumers’. Leary nails Ben’s ambivalence nicely but his false moustache is very obviously fake – and it’s here that I realise I have begun to see the play and production as a work of conscious artifice in itself.

Initially I was somewhat appalled at the obviously painted flat-planed fireplace that stands upstage-centre in John Hodgkins’ otherwise splendid evocation of a village hall, backed by hints of the industrial might of mining machinery. Now I’m also seeing that moustache as if it was painted on rather than grown.

Similarly I reconsider my initial concerns about the clean, neat and tidy nature of the men and their clothes (designed by Sheila Horton): not a speck of coal dust, a sweat stain or a hole in need of darning to be seen in their otherwise true-to-the era turnout. Did they really put on their best clothes to go to a WEA class or is it that they always dressed up for the photos that have informed the costume designs for productions around the world? Or are we seeing them as they see themselves?

The first act ends with a sudden stylistic shift, never to be repeated, where the characters narrate their experiences of visiting the Tate Gallery directly to the audience. “You take one thing and turn it into another,” one character concludes, “and transform who you are.”

The device of projecting background information, scene titles and images of the actual pitmen’s paintings while the characters view them works well for an end-on space (AV and projections design by Johann Nortje). But I find the unrealistic orientation of Robert’s easel to the person he’s painting quite distracting, in a late scene. And Jimmy’s powerful soliloquy about going down the mines when he was still a boy is diluted by meaningless movement.

Otherwise the play flows seamlessly through its eighteen years, leaving us to imagine the individual processes each man went through to develop their skills and produce the paintings we see. Overall it transcends its immediate subject matter to leave a strong impression of lives transformed by art, as Britain’s post-industrial society itself undergoes massive change.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

*The Pitmen Painters opened in Newcastle in 2007, transferred to the Royal National Theatre, toured the UK, played a limited season on NYC’s Broadway in 2010 then opened on London’s West End in 2011. Its New Zealand premiere, directed by Patrick Davies, was at Dunedin’s Fortune in October 2010, followed in Auckland by a (potent pause) Productions season in November 2011.

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Great play thanks to first class cast

Review by Ewen Coleman [Reproduced with permission of Fairfax Media] 06th Oct 2014

Lee Hall’s play The Pitmen Painters, inspired by real life stories from William Feaver’s book, currently playing at Circa Theatre, not only provides a great nights entertainment but is thought provoking and educative, canvassing such topics as art, culture, education and the working class. But above all it shows, without being patronising or sentimental, that within everyone there is a spark of creativity regardless of class, race or creed.

The Ashington Group are a bunch of Northumbrian miners who, as part of the Workers’ Educational Association, engage an art teacher from Newcastle, Robert Lyon (Gavin Rutherford), who is as upper class as they are working class, to run an art appreciation class.

In the group are George (Patrick Davies), the dour stickler for following the committee rules, Oliver (Guy Langford), the sensitive one who has the potential for becoming a professional painter, Jimmy (Richard Dey), the no nonsense down-to-earth tell-it-like-it-is guy. Then there’s the innocent and naïve Young Lad (Simon Leary) and Harry (Phil Vaughan), the only non-miner who relishes quoting Marx at every opportunity but has a heart gold.

Over a period of 13 years a synergy develops between Lyon and the miners and through the course of the play we see, under Lyon’s tutelage, not only how the group develops and grows but how this is a journey of self discovery for the men, albeit differently for each, and how with no education and little money, they become celebrity painters.

They are also aided on their journey by Helen Sutherland (Catherine Downes), an extrovert and art patron.

And in this production what makes Hall’s play work so effectively is Ross Jolly’s astute directing and superb casting of all the characters. Without exception each actor brings a depth and confidence to their performance that not only brings out the humour in the play but often the underlying moments of anguish, anger, animosity and many other emotions as they go on a rollercoaster ride to stardom.

Also adding much to the success of the production is John Hodgson’s multifunctional set and particularly Johann Nortje’s creative integration of slide projections of the men’s paintings that allows the audience to be involved as much as the characters in the discussion of their work to make this excellent production of a great play a most satisfying evening of theatre.

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Comments

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Comments