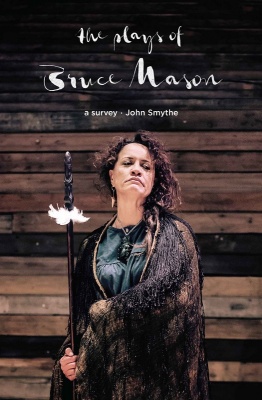

THE PLAYS OF BRUCE MASON a survey

Playmarket Bookshop | Victoria University Press | Unity Books, New Zealand wide

18/08/2016 - 31/12/2016

Production Details

Bruce Mason (1921-1982) was a playwright by vocation and widely regarded as New Zealand’s best. Yet while The Pohutukawa Tree, The End of the Golden Weather and Awatea have enjoyed great success, his seven other full length plays have unaccountably been ignored. His four award-winning short plays, a comic operetta, three other solo plays and many review sketches have also slipped below time’s horizon. Then there are his teleplays: three broadcast after his death and one that was never produced.

The Plays of Bruce Mason is the first comprehensive survey of Mason’s dramatic works. In capturing particular times, places and people with eloquent insight, humanity and wit, his plays invariably distil timeless and universal themes with distinction. In this critical overview, Smythe interrogates each text to reveal a master craftsman’s artistry, at the cutting edge of socio-political awareness.

Revelations about Mason’s private life, necessarily secret at the time, and the discovery of a very personal play text, add to our understanding of his works. This book makes a strong case for Mason’s plays being re-evaluated and taking their rightful place in contemporary New Zealand theatre.

Purchase THE PLAYS OF BRUCE MASON a survey

from:

Playmarket Bookshop

Victoria University Press

Unity Books online

Theatre , Book ,

Takes every opportunity to take the plays back to ‘Bruce the man’

Review by Ralph McAllister 18th Aug 2016

Book review: The Plays of Bruce Mason by John Smythe

Reviewed by Ralph McAllister, published by Victoria University Press.

From Nine To Noon on 07 Dec 2015

Listen (duration 9′ :51″ )

Nine To Noon for Monday, 7 December 2015

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Skimming the works of a master

Review by Roger Hall 18th Aug 2016

NZ Herald Canvas Magazine

Saturday Jan 23, 2016

Book Reviews

Books

Canvas magazine

The first comprehensive survey of playwright Bruce Mason’s dramatic works has left fellow playwright Roger Hall in a reflective frame of mind as he considers Mason’s contribution to New Zealand theatre

Last month, I watched a re-screening of that charming movie, Pleasantville, in which the main characters get transported back in time to a small American town, where everything is in black and white, and no one wants anything to change.

It seemed vaguely familiar. Then I had it: it reminded me of New Zealand when I arrived from Britain in 1958. One of writer Bruce Mason’s satirical songs (which gave its name to a show) was We Don’t Want Your Sort Here, a mocking attack on those who reject anything outside the orthodox. It could well have been sung by Pleasantville’s citizens.

In 1958, Mason was struggling to make a living – any sort of living – as a playwright. There was no television here then. Shops were closed all weekend, so people were more active (though a lot of that activity meant do-it-yourself on a grand scale, including cleaning the car once a week). [More]

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Comments

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

The play’s the thing

Review by Helen Watson White 18th Aug 2016

Bruce Mason’s drama influenced our cultural landscape and an insightful critique explains why and how.

By Helen Watson White

In The Listener Books

21st January, 2016

Actor, author and critic/founder of online journal Theatreview John Smythe has achieved in this welcome book a comprehensive critique of the work of Bruce Mason (1921-82), a major playwright who only late in life received some of the recognition he was due. Smythe and Mason’s daughter, Belinda Robinson, stress that it’s not a biography. However, it does provide an excellent basis for understanding Mason’s growth over nearly four decades in the profession he loved, with family, friends and part-time journalism supporting his endeavour until he died at 61 “at the peak of his creative powers”, as Robinson says in her foreword.

Generations of theatre lovers acknowledge a debt to Mason’s pioneering work. In his 1998 book Bums on Seats, Roger Hall recalls an early authorial performance of The End of the Golden Weather as “not only the best night I’d had in the theatre in New Zealand”, but “one of the best nights I’d had in a theatre anywhere”. [More]

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Comments

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Notes … mainly about Bruce and two or three of his plays

Review by Dean Parker 18th Aug 2016

In the last month of last year I wrote in a sort of diary I keep: “New book about Bruce Mason’s plays, written by John Smythe, published by VUW Press. Starts off with a chapter on New Zealand drama up to WWII. Then follows a very close description and analysis of all Bruce’s stage and TV plays, most of which are rarely performed these days and some of which were never performed in Bruce’s days and certainly not thereafter…”

I carried on with what turned out to be a fairly longish stream of comments. Later, Roger Hall emailed me and asked what I thought of the book and I went back and read my notes and fashioned them into something coherent and augmented them with earlier notes I had made after watching Pohutakawa Tree and Awatea and re-reading the ‘Nights of the Riots’ section of The End of the Golden Weather. I sent parts of this to Roger. I think Roger did a review of his own for the Herald.

I’ve been asked to review the book and I don’t have time to do it properly so I’m offering this, which makes notes about the book but it’s mainly about Bruce and two or three of his plays. And perhaps it’s not very considered. It reads as a terrible put-down of Bruce, and I didn’t mean it to be, it’s just that I was concentrating on a narrow range of criticisms. So I’ll continue with the piece, in lieu of a proper review …

Bruce is quoted more than once for his emphasis on eloquence, and his admiration for the eloquence of Maori. While he could frequently conjure up a magical spell—as with End of the Golden Weather—he could also turn verbose. He seemed to see the stage as a platform for speeches and John Smythe comments on the difficulty those from the world of the screenplay had with him. Screenplays are largely the world of snappy or even non-existent dialogue and not with rolling monologues. Bruce wrote some episodes of the early NZ soap Close To Home and it’d be fun to compare his drafts with the script editor’s re-writes; I can imagine many lines crossed out by soulless brutes.

The most interesting chapter in the book is the one that is primarily biographical, dealing with Bruce’s homosexuality. It’s a chapter well wrought by the author. This Bruce Mason, the one who tours his one-man shows from town to town and picks up casual bed-mates to take back to his hotel unit, appears in his letters but never his plays.

He was happily married with three children, but seemed to have had many male lovers, two of whom were clearly very important in his life.

One of them kept the very candid letters sent to him and John Smythe quotes wonderfully from them. This lover went on to write a doctorate thesis on the male homosexual in a heterosexual marriage and the thesis isn’t quoted from, which is a pity; there must have been pertinent material there.

Inevitably one of Bruce’s pick-ups in Christchurch took it upon himself to write to Bruce’s wife and sneer, “Do you know that your husband is an old lecherous pansy, well known all over NZ for it? The whole of Christchurch is laughing about you.” She was of course upset, but it was an open relationship and she herself took lovers. Someone should write a play about it. Entertaining Mr Mason.

I recently saw two of Bruce’s plays up here in Auckland, The Pohutakawa Tree and Awatea, both done by the ATC. I saw Bruce performing End of the Golden Weather back in the 1970s. (I also remember driving down from Auckland to his funeral, in St Paul’s in Wellington, in January, 1983, with Mervyn Thompson and Tim Shadbolt, and on the way back there was so much talk going on in our car that we missed the turn-off at Bulls and sometime later I noticed the shores of Lake Taupo were looking like ocean beaches and suggested we ask the road gang we were approaching what highway we were actually on, cause it wasn’t State Highway 1, and Shadbolt moaned, “No!” and said, “They’ll recognise me and tell the papers! It’ll be everywhere, Dean—‘Shadbolt doesn’t know where the fuck he is again!’”.

The Pohutakawa Tree is certainly one of the most substantial NZ plays you’re likely to see, gravely worked through, so different from the slight pieces we see on stages today. But it doesn’t come across as a play by someone who wanted to write about things that concerned them. It’s more a play by someone looking for a subject that would fit a particular frame. And the subject seemed very close to that paternalist Pakeha lament for the dying of a grand race, the twilight of the Maori people.

Aroha won’t leave her remnant acre of land. She’s the tragic, emblematic figure needed by Bruce. She won’t leave and join her people who, having lost their tribal lands to settlers, have resettled somewhere else where they’re described (by what I take to be the author’s mouthpiece, the vicar) as being happy in a very non-Pakeha way—that is, guitars and that, not caring for the morrow, living off the land, etc, a place where the vicar believes there is true contentment and reports back for us.

Now you could argue that Aroha’s wrong politically, that she should retreat and re-group with her people and live to fight another day. However the political matter of a fight-back is never raised – it’s all about loss of grandeur.

But then you come up against questions like: where is this land the tribe has acquired (50 acres with 30 dwellings)? How did they get it? The hard reality was everyone in the displaced tribes was dispersing into the towns looking for work, that once ancestral land was gone there was no replacement (and couldn’t be, of course). And with living conditions for Maori rural dwellers pretty grim, how did the tribe maintain the simple Pacific paradise existence described in the text?

It’s all a bit unrealistic.

Bruce, in the The Pohutakawa Tree, was certainly aware of the ironies of race relations. He has a pioneer pakeha family lamenting the wrench of a 75-year association with the land, has a young Maori lad completely wrapped up in stories of Robin Hood which he acts out with an ancestral taiaha, has tipsy and pretty meaningless Pakeha ceremonies and has a Pakeha asked if he knows many Maori and replying, Yes, he’s got a couple working for him.

And the characters are all basically well-meaning, which makes the play richer and sympathetic and furthers the ironies. But you don’t get the impression that Bruce ever really took a hard look at what was going on, that he was too busy writing a play modelled on something he had in his mind.

Sure, as plays go, it’s a class act. I’m just saying had the play been infused with a bit of cold political thinking, and less of lyrical lament, it would have been a better play.

When it came to Pakeha writers of the time someone like Noel Hilliard, a communist, had more perspective. I also note that once Bruce had done with his Maori plays, he had also more or less done with Maori characters.

With Awatea Bruce goes out of his way to anticipate the inevitable threat of condescension and loads an argument against it. But the form is condescending and can’t help but be. It’s a play from one culture that assimilates another in a way that is clearly a triumph for the author and full of niggling doubts for the audience.

The End of the Golden Weather, as I wrote above, is quite magical. But recently, as an exercise, I picked out the least-known section of it, The Night of the Riots, describing the time of the 1932 Auckland unemployed riots and interspersed it with a similar section from Jim Edwards’ autobiographical Waiting For The Revolution.

Jim Edwards’ father was the leader of the Unemployed Workers’ Movement and Jim was present when his father was batoned down by police at a mass night rally at the Auckland Town Hall in April, 1932. For Bruce, this was the end of the golden weather.

As with Bruce’s account, Jim’s is a description seen through the eyes of a boy: Bruce would have been 10 or 11, Jim 13. Bruce’s description is of the reaction of a reasonably well-to-do Takapuna family to the events, and the personal effect upon him. Jim’s description comes from Newton Gully, the heart of the poor and unemployed, and is complicated by Jim’s growing awareness of his father’s failings. Bruce’s adored father becomes a special policeman to secure the city; Jim’s father does eighteen months jail for inciting lawlessness and taking part in a riot. The thing is, the plain unadorned prose of Jim Edwards’ account is more moving.

In his final chapter John Smythe rounds on the major New Zealand theatres for their failure to perform Bruce Mason’s plays—in fact, to perform so few New Zealand plays. John, by dint of extraordinary diligence, has become New Zealand’s leading theatre critic. Those familiar with his comprehensive blog theatreview.org,nz will be familiar with many of these points.

But claims are made for Bruce Mason which seem pretty extreme – comparisons with Chekhov, John Osborne, Samuel Beckett, etc. You come across a book like Scott Bainbridge’s The Bassett Road Machine Gun Murders, an account of 1950s and early ’60s sly-grog dens and abortionists and marijuana smokers commos and bodgies and moxies and molls and the whole business that underlay the years laid down by Sid Holland and you wish someone had chronicled that rather than, like Bruce, leaving us with the impression of the boring ’50s.

The author frequently pauses to applaud Bruce as being ahead of his time. I’m not so sure. Bruce had this tendency — and excuse me for being such a smart-arse — to pick up any intellectual fad going and become the New Zealand spokesperson for it. I remember seeing him on TV once in his polo neck jumper and elbow-patched jacket explaining to us that the Medium was the Message. Later, inspired by poor old Sartre at the Sorbonne in 1968, he allowed his counter-culture play Zero Inn to be examined and pulled to pieces by tuned-in, turned-on students at Vic, and took their comments aboard and re-wrote it. What fucking madness. Writing a play isn’t an exercise in democracy, and John Smythe notes that the original was far more provocative and compelling that the re-write. (I think the Vic encounter was recorded by local television. No mention is made of the television piece, but it must reside in some archives somewhere.)

Bruce certainly could put characters on stage who were alive and he could write speeches for them.

And his was the quite extraordinary ability to write, remember, rehearse and perform a solo piece in a week. He saw himself as a prophet disdained in his own land, and he was, and thrived upon it, really. But I can’t help thinking someone like Roger Hall, a prophet acclaimed, is the better playwright.

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Comments

John Smythe August 21st, 2016

Thank you, Dean, for your notes in response to The Plays of Bruce Mason – a survey. You suggest you are ‘thinking aloud’ to provoke further conversation so I will respond in kind – as Bruce would undoubtedly have done if he was still alive.

It seems a bit pointless to put him down for not being a communist, socialist or unionist. “It is true I am no Noel Hilliard, Jim Edwards or Scott Bainbridge,” he may have written (in similar vein to his response to a NZ Herald critic in 1960 – see p108). “May I add I am no Janet Frame, Frank Sargeson, Mervyn Thompson, Renée, Dean Parker or Roger Hall either.” He was one voice among a growing number, and an important one who deserves to be recognised for what he was, not grumbled at for what he wasn't.

Mason was a humanist with a strong instinct for social justice; a classically educated middle class man but in no way complacent or blinkered by it as a playwright, even if he did sound rather pompous and opinionated in interviews or public forums. Like Pinter, he loitered in pubs to capture the vernacular he needed. And he was impressionable, as Not Christmas but Guy Fawkes and Courting Blackbird (for example) attest; constantly enquiring to what it was to be a New Zealander, a man, a woman, a husband, a wife, a lover, a parent, a child, a human being. (But not, sadly as we agree, free to publicly dramatise male homosexuality.)

I agree with you (and Ian Mune) that eloquence becomes verbosity when stage dialogue dominates a screen adaptation. However Mason’s stage plays are no more verbose, and often just as eloquent as those of Shaw, Wilde, Coward, Miller, Williams et al – and well translated Chekhov and Ibsen. It’s just that his mirror is reflecting a different part of the world – ours – and we are the poorer for not having seen his plays in production alongside theirs.

Whether he’s writing crisp exchanges of dialogue or longer speeches, it’s important to note Mason is not a polemicist. As I note more than once, his strong suit is to have different characters articulate opposing viewpoints so well that his audience feels compelled to work out where they themselves stand.

You say, “Bruce had this tendency—and excuse me for being such a smart-arse—to pick up any intellectual fad going and become the New Zealand spokesperson for it.” That’s grossly unfair and unworthy of one playwright speaking of another. My perception is that Mason had a socially conscious writer’s awareness of what was afoot in society and a playwright’s compulsion to dramatise it – not to ‘teach us’ with didacticism or socio-political propaganda but to put us and our world on the record and elucidate, enquire, question and provoke us all in the process.

Your commentary on The Pohutukawa Tree is subjectively valid and I disagree with it. I don’t see Aroha as ‘emblematic’. She is as flawed an individual as the other characters. Everyone – as you say – is ‘doing their best’ and no-one has all the answers. But boy does Aroha’s oratory and behaviour wake up many a Pākehā to how Māori have been disenfranchised and what Māori land rights are all about.

Kept within their historical contexts, his ‘Healing Arch’ plays are clearly valuable aids to our understanding of our ever-evolving cultures and progress toward biculturalism. He addressed the collision of cultures with great insight - and as soon as Māori writers began to make their mark he backed off (in, as I perceive it, a climate of bleeding heart judgement and Pākehā guilt) and avoided further references to Māoridom, until his last play, Blood of the Lamb.

Thank you for answering my unresolved bemusement as to how and why Chance of a Lifetime – his alternative version of Zero Inn – had come into being. If anyone was part of the workshop at Victoria University circa 1971 and/or has any knowledge of the video recording, please let us know. I’m glad you agree that “the original was far more provocative and compelling that the re-write.”

As it happens, I will be talking about Bruce Mason’s plays as part of the National Library’s STANDING OVATION: Half a century of Downstage Theatre on Thursday 1 September – details here:

http://natlib.govt.nz/events/bruce-mason-at-downstage-september-01-2016

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Comments