THE RITE OF SPRING (2013)

Allen Hall Theatre, University of Otago, Dunedin

06/05/2015 - 07/05/2015

Unitec Dance Studios, Entry One, Carrington Rd, Auckland

01/05/2015 - 02/05/2015

BATS Theatre, The Propeller Stage, 1 Kent Tce, Wellington

21/05/2015 - 23/05/2015

Production Details

International dance performance coming to the Unitec Dance Studios on May 1-2 at 7pm

The Rite of Spring (2013)

by and with Min Kyoung Lee & João dos Santos Martins

Special guests Kristian Larsen & Carol Brown

Le Sacre du Printemps (2013) is a choreographic performance that explores the irresistible seduction and the act of dancing – to death – from its public exposure. It takes as Le Sacre du Printemps reference (1913) Vaslav Nijinsky of the mythical missing choreography, and its many versions made in the hundred years following. In dialogue with the history of dance and reviewing contemporary ceremony with the theater community, Le Sacre du Printemps (2013) is a work that tests the significance and role of dance, sacrifice, pleasure and death. Dance we do, and dance we must. Between life and death, this is an event without rehearsal.

This work was created and premiered in Portugal in 2013.

Running time: 90 minutes

Venue: Unitec Dance Studios, Building 7, Entry 1, Carrington Rd, Mt Albert

Buy tickets at iTICKET (09) 361 1000

$18 Adults, $12 Concession/Students

https://www.iticket.co.nz/events/2015/may/the-rite-of-spring-2013

Performers: Min Kyoung Lee & João dos Santos Martins

Special guests: Kristian Larsen & Carol Brown

Design:Min Kyoung Lee & Joao dos Santos Martins

Light design in collaboration with Daniel Worm d'Assumpcao & Ricardo Campos

Visual art in collaboration with ISCI Delal

Contemporary dance ,

90 mins

Exhausting,charming, intelligent dance batlles

Review by Jillian Davey 22nd May 2015

Korean performance maker Min Kyoung Lee and Portuguese performer/choreographer João dos Santos Martins have created an exhaustive, intelligent, and exhausting (more on that later) piece of work. The Rite of Spring (2013) isn’t a “show” per se; but more of a university-style lecture/durational art performance.

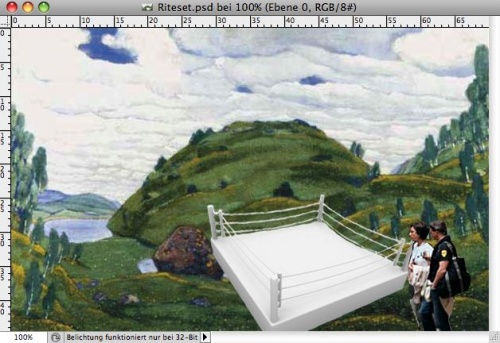

We enter the BATS Propeller Stage to face our co-professors Chris Jannides and Melanie Hamilton, already discussing a Sacre du Printemps video in hushed microphoned tones. It’s reminiscent of a Radio NZ Concert programme and feels like a classroom. Dancers Lee and Martins are in their respective corners; boxers readying for their fight.

And so begins our lecture. Lee and Martins take it in turns to perform an excerpt from Millicent Hodson’s Sacre du Printemps while Jannides and Hamilton discuss Hodson’s recreation of Nijinsky’s original choreography and the hearty division the first performance inspired way back in 1913. (For a bit of background: the first performance of Le Sacre du Printemps allegedly caused outrage and near riot for its portrayal of pagan sacrifice, its avant garde music, and -gasp!- turned in feet and jerky movement.) There were only eight performances of the original choreography and though the music by Stravinsky gained its own fame and was transcribed for the future, Nijinsky’s choreography was never recorded. Hodson, for the Joffrey Ballet in 1987, used interviews, notes, and drawings to recreate, what she believed was, a version as close to the original as possible.

Like a good student, I jot down note after note as Lee and Martins make their way through excerpts of various renditions of this famous work; Martha Graham’s, Maurice Bejart’s, Laurent Chetouane’s, Yvonne Rainer’s, Xavier Le Roy’s, Min Tanaka’s, Kook Soo-ho’s, and one collectively made by company “My Choreography”. Some are danced as solos, some are danced as duet “battles”; pitting one choreography against another. It’s interesting to pick out the similarities and stark differences between these adaptations. For example, the Le Roy choreography (active and literal) has a very different feeling to Tanaka’s (slow and image-driven). Both are extreme in their own way. Commentary by Jannides and Hamilton is informative and pleasing in an intellectual sense. It’s also charming and quietly funny when a bit of good natured banter comes into it.

It’s not until mid-way through, when the dancers take a quick break to change the clothes they’ve sweated through and have a few gulps of water that I realise how easily I’ve slipped into my university days. I put away my pen and paper for a while to enjoy the performative aspect of the evening. As Lee and Martins switch corners, it dawns that it’s a game; a marathon, a sporting event and a spectacle that should be enjoyed by the spectators, not recorded.

It’s Lee and Martins’ stamina and dedication to the project and Jannides and Hamilton’s informed commentary that keeps the pace going and keeps the audience from becoming bored. Their unquestioning tackle of the next (and the next, and the next) excerpt is commendable. Projected prompts sporadically appear on the back wall and invite us to “Applaud”, “Boo”, “Get restless”, “Poke your neighbour”, even “Take your phone out” and “Take a photo”… “With the flash”! They inject well-needed humour to the marathon and are vital as a reminder that this is as much a performance as it is a project.

It’s only the ending which lets this performance art project down a bit. The dancers continue their marathon, obviously past exhausted by now, and our lecturers let us watch in silence. When a group in the audience decide they need to leave, I wonder if this is the ending and in true durational art style, the audience decide when the right time to leave is. I would have been quite happy with that. But after a few more minutes there’s an awkward wrap up by the commentators and we’re told to have a safe trip home. (I’ve pretended that this was due to theatre time restrictions and the original intention was to keep going until either the dancers or the audience gave out.)

We leave feeling a bit worn out but still with a bit of buzzy energy… the sign of a successful assault on the brain. And the sign of a successful project/performance/marathon. Be sure to read the essays and documentation in the programme for some information on how and why this project came to be. It’s a fascinating endeavour.

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Truly striking continuity

Review by Jonathan W. Marshall 08th May 2015

Vaslav Nijinsky’s Rite of Spring, which was choreographed to Igor Stravinsky’s music in Paris, might be seen as a founding text of the modern theatrical, choreographic and musical avant-garde. Though a ballet company, Nijinsky drew on the modernist style of Eurhythmics developed by Rudolf Laban and Maurice Emmanuel (notably in the matching of musical motifs with specific poses). The aggressively stomping dance set in premodern Russia depicted the willing sacrifice of a maiden to the gods of the land to ensure the return of fertility. Rites purported to expose a primal ritual and sexual violence at the heart of human existence.

Ironically, though Stravinsky was to become the champion of measured neoclassicism, his work for Rites had the same frisson and energy as the atonal music and late Romantic compositions of his own time, particularly the operas of Richard Wagner—which were controversial in France because they were distinctly anti-classical, German and (surprisingly for us today who know about how much the Nazis came to love Wagner) supposedly “Jewish” or representative of a miscegenated, semi-Slavic nation.

Rites famously provoked a riot at its 1913 premiere, though as my very brief sketch above illustrates, the response to Rites had relatively little to do with its specifically aesthetic character of the piece, and everything to do with pre-existing political and cultural divisions in France which had flared up after the prominent trial of a Jewish officer, Dreyfus.

Whatever the case, the music of Rites has become a Matterhorn which major choreographers increasingly feel they must at some stage conquer, much like Hamlet and King Lear function for many English speaking actors and directors.

Acknowledging the truly massive number of choreographic interpretations of Rites made over the course of the last 100 years, dance-makers Min Kyoung Lee and João dos Santos Martins have learned several of these versions, and present them to the audience as an exhausting performance lecture in continuity and change in dance.

Versions which feature prominently include the controversial but actually remarkably accurate Millicent Hodson recreation, first produced with the Joffrey Ballet in 1987, and Maurice Béjart’s 1959 production. Whilst this version appears quite late in Lee and Martins’ production, it is logically the next closest to the Nijinsky/Hodson production in that Béjart was renowned for fusing classical ballet elements with freer modern dance. His depiction of Rites as an extended erotic coupling or “little death” of orgasmic union fits closely with the ecstatic Bacchic/Dionysian ambience of Nijinsky’s own version.

A South Korean version is also shown—it is difficult to tell from the wonderful but perhaps too detailed program to work out which one this is—as well as that of Modernist Expressionist dance legend Martha Graham. Again, although Graham did not turn to choreograph Rites until 1984, but much of her earlier work also dealt with women dancing themselves towards a state of furious, near terminal ecstasy (Errand into the Maze, 1947, or Cave of the Heart, 1946, anyone?).

The more atypical version by the company My Choreography from 2008, where dancers improvised around themes, and then danced what they could remember of the previous night until a stable work began to emerge, provided an unusual though slightly idiosyncratic variation to the program of Lee and Martins.

More logical was the inclusion of the version by postmodernist dance legend Yvonne Rainer, a supposedly “vaudevillian” version which meshed poses from the original dance with others taken from television, comedy, and so on. If Nijinsky, Béjart and Graham all represented various versions of Modernism, Rainer offers a more post-WWII, media-savvy version, as you would expect from a postmodernist.

For those versed in the history of Rites and the 20th century choreographic obsession with ecstasy, it comes as no surprise that Pina Bausch’s stomping, circling version concluded the proceedings for the evening as the last new piece introduced.

Bausch is often seen as signalling a return to the emotional inflection of mid twentieth century dance, whilst mixing this with a resolutely abstract and at times even sculptural as well as folkloric approach. This relatively orthodox presentation of dance history history is echoed in how we move across various recordings of the music also, only to end with the version conducted by the all but unchallenged master of late 20th century art music Pierre Boulez in France, whose own compositions draw extensively on atonalism, Stravinsky, Wagner, and electronic musics.

So far so conventional then.

More innovative is the way Martins and Lee present these danced samples. Typically, one of the dancers performs on his or her own a short section from one of these choreographies, whilst Brown and Larsen offer some comments and context via microphones on a table. As the evening continues however, different works are paired with each other: Béjart and Bausch for example, with one dancer dancing one piece (Lee does My Company) and the other a different work at the same time (Martins does Bausch). Moreover, whilst the gestures employed by Graham and Bausch are overall more more flowing than Nijinsky’s stochastic, isolated poses and leaps, all of the versions presented are highly physically demanding, especially when key climatic moments from the score return over and over again.

Brown and Larsen come to resemble then commentators at a dance marathon of the 1920s and 1930s (a phenomenon immortalised in the bleak film They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? 1969). Going back before Rites to other dance classics such as Giselle or The Red Shoes, Lee and Martins perform that age old myth of the dancer who dances him or herself to death. Certainly the battle between maintaining precision versus visible exhaustion on the part of the performers adds a seductively appealing sadistic element to watching this performance-lecture.

Larsen and Brown devise most of their text themselves, and whilst I would quibble with some of the details presented, this is at least as much a performance as it is a lecture. It would therefore be obtuse to expect the speakers to not also be playing with poetics as much as factual detail. Certainly the piece functions as a challenge to all in the venue on quite how to interpret this great myths of twentieth century culture, and the clear difference and disconnection of the seated speakers at the side and the sweating dancers encourages us to approach all elements of the piece sceptically.

Nevertheless, as a historian of fin de siècle France I do find the acceptance of the myth that the “riot” at the opening was the response of an audience to unprecedented aesthetic challenges spontaneously invented by Nijinsky and Stravinsky somewhat tiresome. Do not forget that Nijinsky choreographed after the premiere of works by not only Wagner, but also after Symbolist and Decadent theatre had been sweeping the stages of Europe, let alone the work of choreographers Emmanuel, Isadora Duncan, Loïe Fuller, and others. Fortunately, by visibly placing our speakers at the side and in opposition to the dance of Martins and Lee, the text itself is rendered questionable and more of an offering than anything else, and I for one welcome the commentary of Brown and Larsen.

Brown also notes the controversy which Hodson’s version elicited. She muses as to if one can in fact ever revive choreography, without the bodies of the original dancers. Dance is here constituted as an art defined through the immediate, living presence of a body in communion with the audience in the venue.

Again whilst I respect this position (powerfully made by academic Peggy Phelan), it has been fairly soundly trounced in academic scholarship by the likes of Phillip Auslander. Nijinsky’s work is in fact quite unusual in that we have many sources. There are quite a number of photographs (one would like more of course), some records of notation of the dance itself, the full musical score exists (although Stravinsky himself did modify it over time), and a large number of audience accounts. In short, amongst the history of modern dance, this work—as well as perhaps Nijinsky’s L’après midi d’un faun of the previous year—are easier to restage than a great many others one might name.

Although the text suggests that what is being performed is a kind of ghostly dance, a dance around an absent work which we will never know, as the evening reaches its conclusion, the different mash-up versions begin to intercut and merge in an ever more frenetic and inconsistent pattern. What at least I took away was not the difference of these works, but the truly striking continuity of them. All of these productions quote a number of movements which we now unequivocally recognise as “Nijinsky’s choreography.” The leaping body, the body placed along a parallel plane almost like an Ancient Greek bas relief (also seen in Duncan’s work), the pointed gestures of the hands and toes, the turning outward in parallel of the feet and the splaying of the legs to make a rhombus below the hips: these are all “Nijinsky poses” and every one of our later choreographers uses one or more of these.

Indeed for my money, the most strikingly original of the versions cited here is that by butoh legend Min Tanaka of 1990, which unlike most of the other segments, is only performed by Lee. As Brown and Larsen observed, Tanaka was very interested in the proximity of life to death. His is a dance of spasms and of sensing one’s internal peaks and journeys towards, or out of, ecstasy and communion. Butoh has been called an “anti-choreography” in that it has relatively few recognisable gestures, instead generating an ever changing, almost formless or spastic body.

Uniquely amongst the choreographers evoked then, Tanaka quotes none of Nijinsky’s movement. His is rather a compelling search for internal bodily consciousness. This might seem to have nothing in common with Nijinsky beyond the interest in ecstasy and sacrifice, but it is worth recalling (poorly known that this is) that Tanaka’s mentor Tatsumi Hijikata quoted the work of Nijinsky, especially Après midi d’un faun, in his own work (French speakers can refer to http://www.regardaupluriel.com/buto-enigmatique-danses/). Butoh is much about a dialogue between elements of form and structure which the more fluid body interacts with, as it is about anything else.

Overall then, one must conclude that this project offers an all but unprecedented opportunity to revisit the history of modernism and dance, and to poke at some of the continuities and discontinuities which it provokes. Modernism has not in fact passed, but has rather now become part of the canon we reinterpret. In critically engaging with this history, Lee and Martins give us a moment to reflect, whilst their own bodies collapse, all but destroyed by this attempt to re-embody the fervid energies of this exciting past.

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Comments

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Comments