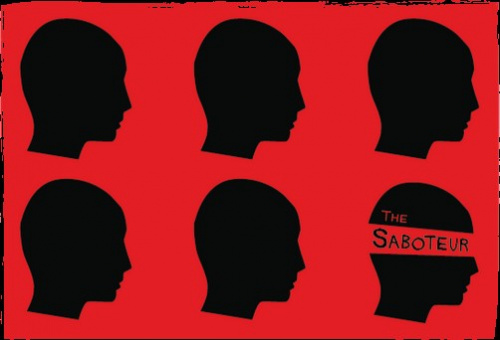

THE SABOTEUR

BATS Theatre, The Heyday Dome, 1 Kent Tce, Wellington

13/10/2019 - 13/10/2019

Production Details

Six performers are all working hard to put on a good improv show. Well, almost all of them. One of them is trying to sabotage the show without getting caught. Can you, and the other performers, work out who The Saboteur is before the evening is ruined? Join us for an evening of subterfuge, treachery, backstabbing, and laughs!

Jim Fishwick is an award-winning director and performer. He specialises in interactive, intimate and immersive performance, and is the General Manager of Jetpack Theatre Collective. He is an ensemble and faculty member at Impro Melbourne, and a former national champion improvisor. He finds writing in third person kinda weird.

BATS Theatre: The Heyday Dome

18 October 2019

at 7pm

Full Price $20

Concession Price $15

Group 6+ $15

Full Price Season Pass – 3 shows for $45

Concession Price Season Pass – 3 shows for $36

BOOK TICKETS

Accessibility

*Access to The Heyday Dome is via stairs, so please contact the BATS Box Office at least 24 hours in advance if you have accessibility requirements so that appropriate arrangements can be made. Read more about accessibility at BATS.

Theatre , Improv ,

1 hr

Risking pride in search of extra excitement

Review by Lyndon Hood 20th Oct 2019

There’s a genre of modern parlour game that involves a majority of good citizens trying to discover and eliminate secret traitors in their midst, while the secret traitors try to convince everyone else to eliminate anyone else. Common variations are Werewolf and Mafia, and I’ve never played them. (Honestly.) The Saboteur is not exactly structured like these games but I do get a hint of the paranoid double-guessing they inspire when I read its publicity blurb:

“Six performers are all working hard to put on a good improv show. Well, almost all of them. One of them is trying to sabotage the show without getting caught.”

The basics of improvising badly are fairly established. Most famously, one can fail to ‘yes and’ – either denying or adding nothing to the world your scene partners have created. But the idea of improvising maliciously is new. How do you do that, and succeed, without making it obvious to an audience of (let’s face it, this is the New Zealand Improv Festival) mostly improvisers? If they dare do this, what else? Is there some kind of double bluff here? What’s really going on? I enter the BATS Dome soace prepared to be betrayed on almost any level.

So it’s almost a spoiler to say there are no spoilers. As Jim Fishwick, the show’s creator and MC, explains with comical grimness at the show’s opening, six players claim to be working within the agreed principles of improvisation and the mutual trust that underlies them to put on “A good. Comedy. Show.” But one of them is, subtly or otherwise, working to undermine the very scenes that make up that show. Cue enthusiastic gasps of horror from the audience.

These six improvisers enter one by one. They introduce themselves with a brief summary of their own philosophy of improv, and each declares, “I am not the saboteur.”

They are, at least initially, divided into teams. ‘Team Green’ is Rebecca Stubbing, Cameron Watson, and Jennifer O’Sullivan. ‘Team Blue’ is Brendon Bennetts, Tara McEntee, and Siobhan Finniss. The teams take turns playing short scenes based on prompts issued by Fishwick: some simply open suggestions of settings or characters; some with the additional prompt of a traditional improv game.

Many of the games are ones I personally haven’t seen in some time. Some of those may be neglected specifically because they’re easy to do badly. For example, both ‘Death in a Minute’ (some time during a one minute scene, someone dies) and ‘First Line/Last Line’ (where the players are given the opening and final lines of the scene) are subject to the problems that come from improvisers and audiences knowing what’s going to happen next.

As it happens, the scenes are all good fun. In their way.

It was always going to be difficult to pick one person’s destructive influence: improv scenes are destroyed and remade in every moment; among these players ‘bad improv’ is less likely than mismatched ideas about what you’re trying to achieve (the statements of improv philosophy become relevant here); malice is camouflaged by others’ reflexive habit of spinning what could look like a ‘mistake’ into gold.

Team Blue’s first line/last line scene is a case in point. Finniss tempers what seems to be her baseline exuberant cheerfulness, trying to pin down Bennetts’ character to commit to a relationship. She escalates: “That’s what you said twelve years ago!” Then McEntee joins in that game, as the couple’s child (followed up by revealing she is one of several). The audience is enthusiastically aghast. Bennett pauses to digest all this (or is he just stalling?) then struggles in the direction of resolving the relationship and the assigned last line (to do with the opening of a supermarket). McEntee pops back in to declare daddy’s “special friend” is waiting downstairs.

They get there in the end. The scene is simultaneously a train wreck and one of the best of the show.

Of course there are other improvisers than on the stage. In another scene Darryn Woods on lighting manages to bring up a spot perfectly on cue as an improviser mimes opening drawing room curtains. He is probably not the saboteur.

After one round, the players are invited to offer ‘suspicionals’. Each takes the spotlight and explains who they (claim to) believe is the saboteur, and why. Perhaps for some failure of supportive improvisation, perhaps for some suspicious tell. Bennetts may be stretching a little for condemnation when he cites the fact Watson had claimed to be aiming for “big dumb” improv yet had performed quite nuanced scenes.

After the next round we all take to our phones. The audience is invited to a specially-created website to vote for who they think is the saboteur. The players are completing a quiz. The exact nature of the quiz isn’t explained but we are assured the result, as compiled by laptop-equipped scorekeeper Matt Powell and reported by Fishwick, represents “who knows the least about who the saboteur is”. It’s all very dramatic, slightly fiddly, and somewhat subject to technical complications. It’s also mysterious: aptly enough, we have to take it on trust.

The lowest quiz score decides an elimination: the first to meekly leave the stage is Stubbing. We are told that 16 percent of the audience believed she was the saboteur. Bennetts is the next to fall to this cycle of scenes, recriminations, and eliminations. The players mostly seem to believe Team Blue harbours the saboteur (their scenes have generally run less smoothly, if with more excitement) and there is audible surprise from the audience as Finniss is eliminated. Statistics confirm she was the suspect of 48 percent of the voting audience.

With the second elimination, the teams disband and scenes open up to all players. The challenge for the final three players is to a Shakespeare scene. It’s difficult to draw any conclusions from that one because none of the remaining players are much good at Shakespeare.

The format is, in many ways, a harsh one for the improvisers. Your foibles and habits are subject to harsh judgment. Is, for example, O’Sullivan’s increasingly obvious silliness over the course of the show – a flagrantly over the top portrayal of a mythical ice queen, closely followed by a scene that is entirely taking the offer of “counterfeiter” as someone who fitted counters – a good thing, normal variable improv behaviour, or proof of betrayal? The (in most cases) real shock at these accusations is part of the fun but, in a less supportive environment than this festival, could be destructive.

There’s enough collapsing trust in the world as it is. So it’s good that what I see is some improvisers who have agreed to risk some of their pride and push the edges of normal improv in search of some extra excitement. It’s an agreed betrayal, savaging the occasional scene but enhancing the show.

After a final quiz, O’Sullivan is declared the winner having correctly identified the saboteur: McEntee, apparently due to out-of-character playing style. It all seems obvious in retrospect, particularly for that first line/last line scene and the ingeniously destructive method of doing something to crash everyone else’s plans for the scene that the audience likes. But one could construct a similar story about everyone else. They are all saboteurs. It’s improv.

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Comments