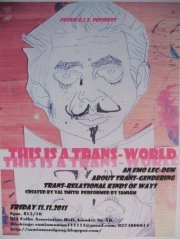

This is a Trans- World with Sam I Am

As Is Performance Space, 377 Princes St, Dunedin

03/02/2012 - 03/02/2012

Auckland Old Folks Association. 8 Gundry Street (off K' Road), Auckland

11/11/2011 - 11/11/2011

Production Details

This work has grown from research into the relationship of/between somatics and performance, influenced by the frameworks of Contact Improvisation and Vipassana Meditation, as well as Butoh and Body Mind Centering, amongst other practices. Val is an experienced teacher and improvisation performer working since 2000 in NZ, Australia and the U.S.

Lights: Elispeth Fougere

Music: Cocorosie, Antony & The Johnsons, De Novo, unknown artist, Led Zeppelin, James Brown, and various artists from the Reader's Digest Love is in the Air anthology

Song: Daylight and the Sun (Antony and the Johnsons)

Photos: Georgia Giesen & Christiina Houghton & Elspeth Fougere & Val Smith & Shalene

Drawings: Val Smith

2 hours

Twisty/Straight, Ironic, Intriguing

Review by Jonathan W. Marshall 06th Feb 2012

After touring Dunedin in last year as part of October’s fabulous Qubit festival of Live Art (also distinguished by works from The Yellow Men, Mark Harvey, Kiri Beeching and Del McLeod), Val Smith was back down south for a full length version of her interactive mixed performance. Smith has also staged previous versions of this material in Auckland.

Qubit was housed within the sparse but atmospheric surrounds of the Anteroom, a former Masonic Hall out of town in Port Chalmers, with little if any professional effects. Spectators sat around the wall (or, in the case of Harvey’s performance, huddled in the centre trying not to be trodden on as he zoomed about backwards). A basic personal address system was at one end, but overall, the performance had a run-down artist studio feel. In the absence of formal, theatrical framing, works tended to feel like they were closest in aesthetics to 1980s Performance Art in galleries, old-style hippie “Events” or “Happenings,” or other concepts staged using experimental or aesthetically-unclear venues.

The As Is Performance Space in Dunedin is a members- or by invitation-only affair. Also a converted-style loft, the select nature of the audience helped to keep the sense of experiment alive here. Nevertheless, the staging of Trans-World was more formal and employed significantly more by way of technical support and framing. At one particularly striking moment, for example, a miniature stage at the rear of the space was revealed to show a framed sitting room within which Smith rested, gently singing “Daylight and the Sun” by Antony and the Johnsons, whilst behind her hung a slightly hyper-real 1970s landscape painting of waves converging to an impossibly sharp, V-shaped point before the edge of a glowing seashore.

To characterise this as a dramatic or specifically theatrical version of Smith’s aesthetic would be going too far. Even so, the use of music, both professional and D.I.Y. lighting (spotlights and torches) and other devices made this a more overtly aestheticized production.

I begin with this to suggest that this is perhaps the strength of this production, in that Smith now has a more complete, rounded show — albeit one composed of various short scenes loosely strung together. She has enough material to eke out audience attention for an evening, and so the slightly slipshod yet serious meditations on gender and performance which she offers come across as gesturing towards some kind of overall argument or thesis, rather than the more uncertain, tendentious aesthetic questioning of Qubit. The previous Theatreview reviewer suggested that this might be considered a critique of “realness,” an interpretation with which I would broadly agree.

This therefore places at the centre of Smith’s work a deliberately shaky integration, and interrogation, of most aesthetic values one might associate with theatre or dance. Smith’s episodic approach is characterised by a studied awkwardness and vexingly uncertain, self-conscious faux-seriousness. Smith never simply acts or expresses herself. She rather talks us though some of the more bizarre and ridiculous obsessions behind each act, no matter how logically incongruous they are, before striving to realise her own concepts, however inexactly.

Between light comedy and critique, the affective structure of the work is no less illusive than Smith’s professed gender ambiguity or slippage. The form and style of the show might then be considered closest to that of contemporary cabaret, a mixed, episodic format, which can seesaw, sometimes happily, at other times incongruously, between popular culture, sex show, burlesque, stand-up comedy, gallery-style Performance Art, rock’n’roll, and other forms.

Smith’s heirs and peers are everyone from Laurie Anderson (whose monologues on gender and the strangeness of everyday life remain touchstones for so much contemporary art), through to Annie Sprinkle and other post-1970s promoters of sex-positive, risqué Performance Art, from the unashamed glitz and near-bisexual masculine adornment of Glam rock, through to the in-your-face aggressive bisexuality of electroclash icon Peaches, or — in a more poetic yet no less funny vein — the spoken-word lecture style of Spalding Gray, Eric Bogosian, or even Henry Rollins.

Smith’s principal medium, at least in the first sections, is female-to-male drag. I am not well versed in the New Zealand scene here, but again, the recent seepage of drag from popular culture and music into the more overtly theatrical work in Melbourne of the wonderful Moira Finucane (whose drag persona is so convincing that even though I know her quite well, when I first saw her perform “Romeo,” I did not recognise him/her until she dropped her trousers!), or Sydney’s more overtly populist Kingpins, both of whom have long been the darlings of both the art world as well as the general public in south eastern Australia. In short, Smith has some tough acts to follow on the international scene.

One of the more interesting aspects then is that, in between her various drag personas (Smith is not the first to notice that the music of Led Zeppelin, in the ridiculously explicit reference to masculine sex acts of “Whole Lotta Love” and “The Lemon Song,” actually comes across as quite queer, especially when mimed in drag) and Smith’s droll delivery of semi-improvised explanations and quasi-lectures about gender, the imagery she associates with gender in her show (she tells the audience that she adores gold, but wants to dance in a fully feminine or XX-chromosome manner, so named one section “Solid Gold D.I.X.” — D.I.Y. with the double- or triple-X, as Peaches’ would put it) and other materials, she initially sports a fairly impressive false phallic package down her trousers.

The result is that, in the context of the title of the show, her queer stripping acts are intriguing in a way that is not normally the case. They flirt with, but refuse, the possibility of telling us “the truth” about Smith’s sex, if not her gender. By keeping the body largely hidden, but poorly dressed in ill-fitting jeans and a baggy men’s shirt or hoodie, Smith’s performance remains fundamentally unreadable or impossible to confirm according to “natural” bodies. Gender is, as many theorists have observed, a performance here.

Smith, though, is deliberately bad at it. I do not doubt, as the other Theatreview reviewer claims, that Smith could, and may well have, passed as a male. Her self-conscious, studied awkwardness throughout the show however endlessly reminds audiences that whatever Smith “really” is, performances can only very imperfectly frame this.

A highlight of the show, and a section which also featured in Qubit, includes Smith, in the most droll, deadpan fashion one can imagine, standing on a chair in her oversized men’s garb, explaining to us that in dance, one is often told to create lines in the body which are physically “straight.” She indicates this with her forearm bent sharply outwards at the elbow, extending in a bony line which terminates in one finger pointing sharply out from the hand, thereby giving us, and the concept, the finger.

She then tries to explore, live before us, if it might be possible to be straight in some parts of the body, but “bent” and “twisted” in others, without being “fucked up.” As she ties herself in knots and teeters on her perch, she notes that “Yeeee-ah, not feeling very relaxed there. That’s kinda fucked.”

These comic physicalisations of such flatly-related terms applying to normative distinctions between masculine and feminine, straight and gay, alternate in her performance with other darker, more serious, or overtly beautiful sections.

In addition to a bent over, four-limbed walk framed by Smith under the heading of “Gay Shame,” another notable image was where Smith tried to show a form of “cellular breathing” and embodiment.

Drawing on butoh and Body Weather approaches, the idea here was for Smith, before our eyes, to try and register a sensation in her body of all of the cells and pores of her body opening to everything else inside and out. The body becomes fluid and interconnected, and hence both masculine and feminine.

Smith stands with one arm raised to the heavens like a soft, wafting antenna, with the other arm bent, forearm running parallel and out from the body as though holding between both hands before her a great ball of energy. Fingers waiver, Smith’s eyes close, and small electric pulses, quivers, and intermittent, erratic spasms runs from arm to shoulder and out the legs before Smith swings down and low, legs wide, the high arm now describing an arc which curls these forces and connections into and out of the trunk.

In short, very beautiful, very skilled, and very hard to do, even though the formal shapes and relations are not precisely controlled or predictable.

What I am gesturing at, though, is that in Qubit, it was hard to know if we should take Smith’s explanations seriously or not, or indeed if one could do so, especially within a show designed to make you question linguistic distinctions such as masculine versus feminine.

Many dancers talk about “cellular breathing,” but really, as everyone must admit, it is all a lot of hooey. Cells do not “breathe,” at least not in that sense. It is an image, a metaphor, and when someone says it out loud to you at a performance space over a microphone like a stand-up comedian, it sounds more than a bit silly. Which of course it is. But it might still be “true” at some level.

This wonderfully confusing ebb and flow between comedy and seriousness, between a joke which the audience is in fact in on, or are we too being fooled, was deliciously explored at Qubit. In this full staging, while not absent, the show overall becomes much more set in its ambiance. The cumulative effect of such scenes is not necessarily to further ambiguity, but rather to entrench it within a more inflexible aesthetic and conceptual frame.

In closing, I would like to comment on the other central irony of this work which Smith both wonderfully explores, but which raises as many aesthetic and political problems as it might address. During one of the less effective audience interactions (the so-called Make Out corner where Smith, really getting into hippie mode here, advises two audience members to sit and “just be real together” while Smith leaves the stage), was interrupted by the naked, and so now unambiguously female, Smith streaking through the space screaming that this is the End of the World.

The interjection was so unexpected, so oddball, and yet — in the context of such a deliberately oddball, mixed work as this — so bizarrely apt that the audience almost to a one applauded enthusiastically.

Yet where, I wondered, had the bisexual-meets-transsexual character we had been introduced to at the start of the piece as “Samiam” gone? Gender ambiguity certainly remained, but the uncertain sex of the body beneath this play of gender had been totally erased.

Perhaps this is the point. Female bodies are masculine, just as male ones may be feminine. Smith’s show is designed to ask these questions, as well as to make one giggle. I would nevertheless suggest that while transgendering is not without some radicality and edge in contemporary society, transsexualism and intersexuality remain true taboos. The popularity of even female-to-male drag seems to have made such play “OK” within the wider community, provided the body itself is reasserted. Whatever your gender is (masculine or feminine), or even your sexual identity (heterosexual, homosexual, bisexual), bodies remain static, unchanging, and the ultimate immutable proof of identity; a male is a male, a female a female.

The truly utopian world which Smith preaches to us in her persona of the Trans-Evangelist would however be one where even this would not be true. Maybe this is impossible. But This is a Trans-World points a twisty-yet-straight finger in this direction.

Anteroom: http://www.facebook.com/groups/anteroom/

Val smith and Samiam: http://samiamandgang.blogspot.co.nz/

Laurie Anderson: http://www.laurieanderson.com/

Eric Bogosian: http://www.ericbogosian.com/

Moira Finucane and Jackie Smith: http://www.moirafinucane.com/

Kingpins: http://kaldorartprojects.org.au/_webapp_1098575/The_Kingpins

Peaches and the Kitty-yo Crew: http://www.myspace.com/peaches/

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

The impossiblity of real-ness

Review by Raewyn Whyte 12th Nov 2011

As performer Val Smith explains, near the end of This is a Trans- World, the project began some years ago when she discovered, while improvising, that her gender isn’t fixed, that it is dependent upon her understanding of the relationships between herself and the persons she is improvising with, that it is created in the process of dancing, and that it is possible to have multiple genders at the same time. Since then she has explored various facets of this understanding, most recently focusing on the challenge of how to communicate this multiplicity of genders via performance.

Val is a slender woman, noticeably well centred over her feet, and standing tall, though she’s not that much above average height. An androgynous figure, with her head shaved, her chest wrapped in sports bandages and the addition of a moustache, she pretty much passes as male, and her alter ego Sam I Am (a trans- guy with a twist), in black jeans, black tshirt and hoodie, black wig, baseball cap, and hands thrust into various pockets, is the one who greets arrivals to the performance.

A large mind map sketches out some key ideas for the audience.

realness vs passing the performativity of shame Transitional fluids Us/Them

“trans- evangelism” visible – invisible the queering cloud

dreamgirls in retirement hyphen space gender permeability

cellular consciousness fluid boundaries proud DIX real battles

Sam I Am indicates some connections he’d like us to be aware of, then directs us to choose a seat from two facing rows which provide boundaries for the primary performance space, or two further rows outside them, depending on how close to the action we want to be. Next a quick series of warm up activities — waving the flags which are under our seats, and practicing a series of yells and Mexican waves — and then a quick introduction to Sam I Am’s alter ego – well, Val (a femme hard out) – before they begin to battle it out for the title of MOST REAL.

Over the course of the evening leading up to the final vote, there are 10 or so different sections. Throughout, Sam I Am and well, Val morph in and out. At some point the wig and cap fall off and are nt replaced. The black clothing is swapped for blue jeans with a rhinestone-studded heart-shaped buckle, a loose white shirt, jacket and tie, and subsequently, clothing is removed altogether, layered back on, or off as the occasion requires.

A wide range of performance modes is used to canvass the various themes and issues communicated. There’s a good deal of talk in some sections — most notably a series of wry (and often funny) personal anecdotes about growing up in Helensville; while others are utterly wordless, comprised solely of immersive cellular improvisation — one of these focuses on Gay Shame. Talk and cellular improv are combined in a section which considers the notion of straightness and where it is determined, in the body and/or the mind, with various kinds of kinked-ness, twisted-ness and bent-ness demonstrated along the way to arriving at the logic that straightness is relative.

A Trans-Evangelist is presented — as a cantor, chanting a text derived from social somatics and about the development of connections and empathy, acknowledging the often difficult boundaries between us, but offering a way to move on. Sam I Am in raunchy male stripper mode provides a sharp contrast to that figure. There’s also well, Val’s almost melancholic unaccompanied delivery of the Antony and the Johnson’s song Daylight and the Sun, which contrasts strongly to her hedonistic naked streaking through the space in Make Out Corner whilst volunteer audience members are occupied with a random partner in front of the video camera.

By the end of the evening, we have been thoroughly entertained, provoked , and made to think, as well as being considerably impressed by a much more comprehensive experience of Val Smith the performer and person than we’ve been able to access previously. When it comes to the vote, almost nobody is willing to chose between Sam I Am and well, Val as being The Real-est, as by then we understand the impossibility of the notion altogether.

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer

Comments

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Make a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Comments